MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

May 28,

2017

NEWSLETTER

Roger Moore (1927-2017)

❖❖❖

IN THIS ISSUE

SALZBURG

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

WHY ARE NYC'S RESTAURANTS CLOSING?

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

RUFFINO CELEBRATES 140 YEARS

OF MAKING CHIANTI

❖❖❖

SALZBURG

By John Mariani

When I was in Salzburg last December, the whole town was done up like a Christmas card, complete with horsedrawn carriages, jingling bells, wreaths and garlands, windows piled high with confections, and steaming hot cider sold on every corner.

But

Salzburg at any time of year is a fairy tale city,

quaint without ever being coy, baroque without

being excessive, and in thrall to native son

Amadeus Mozart without being mawkishly idolatrous.

There is grandeur in the 17th century Dom

cathedral (left)

and the Residenz

Palace, once home to archbishops, with a

collection of European art from the 16th to 19th

centuries and its famous horse fountain.

But

Salzburg at any time of year is a fairy tale city,

quaint without ever being coy, baroque without

being excessive, and in thrall to native son

Amadeus Mozart without being mawkishly idolatrous.

There is grandeur in the 17th century Dom

cathedral (left)

and the Residenz

Palace, once home to archbishops, with a

collection of European art from the 16th to 19th

centuries and its famous horse fountain.

There is music everywhere in Salzburg. Streets are

made to stroll through, flanked by arcades, their

store windows displaying beautifully tailored

Austrian jackets and festive dress, dirndls  and loden coats.

and loden coats.

The city is chocolate mad, home to two particular specialties created there, the Salzburger Mozartkugel and the Cappezzoli di Venere, which means Venus's nipples. The former, to be expected in a city where it's said there is a Mozart recital every day of the year, was created in 1890 by Paul Fürst, who won a gold medal for it in the Paris Exhibition of 1905. It is made of dark chocolate and wrapped in special paper, and you can buy it at the four Fürst confectioners in town. Facsimiles abound under other names.

Venus's

Nipples are made from chestnut and

nougat paste in white or dark chocolate—said to

have been a favorite of Mozart competitor

Antonio Salieri—found in their little paper cups

at the delicacy shops Kolbl

Feincost and R.F. Azwanger.

Of course, the city also has its Sachertorte, the rich chocolate-and-apricot cake created in 1932 for Prince Metternich's court guests and forever associated with the Sacher Hotel in Vienna.

Salzburg is also a city of cafés, like the famous Café Bazar, since Mozart’s day a celebrity draw, now constantly full of locals, well-dressed matrons, young women with their school friends, and business people, all on their iPhones and nibbling on croissants and Milchbrot (a sweet milk bread).

Rightly so,

the Old Town, much of it closed to vehicular

traffic, has status as a UNESCO World Heritage

site, and its mix of Romanesque, Gothic, baroque,

and 19th century architecture has largely been

uncompromised by anything too brutally

modern—except for the grotesque Museum der

Moderne Mönchsberg jutting from a cliff

above the city and made even less inviting by the

poor quality of its exhibitions. Far

more appealing in every way is the Salzburg

Museum (left),

opened only in 2007 on Mozartplatz, with its

Glöckenspiel bell tower, whose works manifest the

city’s historic culture.

Rightly so,

the Old Town, much of it closed to vehicular

traffic, has status as a UNESCO World Heritage

site, and its mix of Romanesque, Gothic, baroque,

and 19th century architecture has largely been

uncompromised by anything too brutally

modern—except for the grotesque Museum der

Moderne Mönchsberg jutting from a cliff

above the city and made even less inviting by the

poor quality of its exhibitions. Far

more appealing in every way is the Salzburg

Museum (left),

opened only in 2007 on Mozartplatz, with its

Glöckenspiel bell tower, whose works manifest the

city’s historic culture.

My wife and I stayed at a two-year-old boutique

hotel, the Hotel Goldgasse,

set on a winding street under an archway just off

the Alten Markt in the Old Town center and wholly

devoted to the city’s music and opera. Indeed,

each of the hotel’s 16 rooms  has an

entire wall with a color photo depiction of an

opera production (below, Il Trovatore). The

interior’s narrow winding staircase might pass for

one in the film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, but the

ambiance of the place is that of a private

residence overseen by the remarkable Ulrike

Koller, whose hospitality and interest in her

guests is boundless.

has an

entire wall with a color photo depiction of an

opera production (below, Il Trovatore). The

interior’s narrow winding staircase might pass for

one in the film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, but the

ambiance of the place is that of a private

residence overseen by the remarkable Ulrike

Koller, whose hospitality and interest in her

guests is boundless.

Downstairs is a

traditional restaurant named Gasthof whose

copper pans evoke its origins as a coppersmith’s

house dating to 1573. It also has a copy of

Austria’s first cookbook dating to the 15th

century, from

which are culled some of the ever-changing recipes

used in Chef Philippe Sommerspurger’s hearty,

inventive cuisine, which

includes a signature fried chicken (left) with a

cucumber salad and cranberries (€18.90); a

housemade sausage with sour cabbage, parsley

potatoes and mustard (€15.90); smoked cheese

noodles with crispy onions (€16.90); excellent

Wiener Schnitzel of veal (€23.90); and for

dessert, the fluffy burned meringue dessert called

Salzburger nockerl (€18.50) with vanilla ice cream

and raspberry cream. The wine list is heavy in

modern Austrian labels. And at breakfast there is a

splendid buffet with terrific breads and good

coffee.

inventive cuisine, which

includes a signature fried chicken (left) with a

cucumber salad and cranberries (€18.90); a

housemade sausage with sour cabbage, parsley

potatoes and mustard (€15.90); smoked cheese

noodles with crispy onions (€16.90); excellent

Wiener Schnitzel of veal (€23.90); and for

dessert, the fluffy burned meringue dessert called

Salzburger nockerl (€18.50) with vanilla ice cream

and raspberry cream. The wine list is heavy in

modern Austrian labels. And at breakfast there is a

splendid buffet with terrific breads and good

coffee.

For something

more basic and inexpensive, there is Triangel,

a hangout for locals, especially students, because

the University owns the

building and keeps menu prices in line so that a

good meal can be had for very little. The

blackboard postings each day indicate what's most

fresh and good, the cheery room is chockablock

with old wood tables, and the beer flows freely.

the

building and keeps menu prices in line so that a

good meal can be had for very little. The

blackboard postings each day indicate what's most

fresh and good, the cheery room is chockablock

with old wood tables, and the beer flows freely.

For a far more lavish gastronomic experience there is the unique Stiftskeller St. Peter, set within the monastery walls of St. Peter’s Abbey, whose low street arcade outside gives no indication of the restaurant’s immense size on several levels with eleven rooms. Upstairs there are huge banquet rooms, stunningly decorated, and a thousand people a day come through the restaurant; one room has live Mozart music every night via period costumed musicians. (The composer himself is said to have dined there, and it is claimed this is the oldest restaurant in Europe, dating to 803 AD, and where, legend has it, Faust met the demonic Mephistopheles.) Given its centuries in business, St. Peter has built up a legendary wine cellar, one of the finest on the continent.

My wife and I dined in a small, far more charming and warm-spirited Burgerstube room (right), softly lighted and done in varnished paneled wood, thick tablecloths, hanging lamps, and old-fashioned rathskeller wooden chairs.

Our seasonal menu began with a velvety chestnut and chocolate puree soup and a nicely cooked risotto dauntingly rich with Gorgonzola. They had a pork schnitzel Cordon Bleu stuffed with ham and cheese, served with parsley potatoes and cranberries. The stand-out that night was a lamb knuckle in a well-reduced demi-glace accompanied with potato cannelloni.

We could not resist

ordering another Salzburger Nockerl (below), which

could serve three or four people easily. The

dessert is traditionally made in three mounds of

meringue, representing

We could not resist

ordering another Salzburger Nockerl (below), which

could serve three or four people easily. The

dessert is traditionally made in three mounds of

meringue, representing  the

snow-dusted so-called mountains (rather more like

big hills) in the city, all of them fairly easy to

trek.

the

snow-dusted so-called mountains (rather more like

big hills) in the city, all of them fairly easy to

trek.

I also recommend a visit to one of the loveliest gourmet stores I've run across in Austria, the family-run Koelbl-Feinkost, stacked with local delicacies and wines, including an array of the best the country has to offer. Also good is Rigler’s grocery store to see the panoply of Austrian artisanal foods now available, and Cook&Wine is a new winebar and eatery where you can take courses in Austrian cooking. And to get a true and enduring sense of Old Salzburg, visit the city’s oldest bakery, Stiftsbackerei St. Peter (left), which dates back to the 12th century as a monastery flour mill—still run by flowing water—and bake shop. Each morning the bakers make marvelous sourdough bread whose aromas suffuse the air outside of the little store, which has never seen fit to expand its offerings much beyond a few different loaves of bread and cakes. But once you’ve tasted them slathered with butter and jam, you’ll never forget them, and you will return there whenever you can.

But that’s also

true of Salzburg itself, where one visit betokens

another, at any and all seasons.

- one-time FREE admission to all

city tourist attractions and museums

- free travel on public

transportation (incl. Festungsbahn funicular,

Untersbergbahn lift, Mönchsberg lift, Salzach

River Tour I)

- attractive discounts on

cultural events and concerts

- additional discounts at many

excursion destinations

- in some cases, express entrance

without having to stand in line at the ticket

window

The card is available for

24, 48 or 72 hours.

❖❖❖

By John Mariani

WHY DO NYC RESTAURANTS CLOSE?

You

may notice that I did not

entitle this article, “Why Are So Many

NYC Restaurants Closing?”—which has become a

perennial question posed by the food media any

time a noted eatery closes. Ever

since Prohibition put extravagant Gilded Age

totemic restaurants like Delmonico’s, Rector’s

and Louis Sherry’s out of business in the early

1930s, the media have lamented the economic and

social reasons for a restaurant closing, and

predicted the demise of similar enterprises.

You

may notice that I did not

entitle this article, “Why Are So Many

NYC Restaurants Closing?”—which has become a

perennial question posed by the food media any

time a noted eatery closes. Ever

since Prohibition put extravagant Gilded Age

totemic restaurants like Delmonico’s, Rector’s

and Louis Sherry’s out of business in the early

1930s, the media have lamented the economic and

social reasons for a restaurant closing, and

predicted the demise of similar enterprises.

Yet closings happen all the time, especially in

NYC, where there are more restaurants—about

20,000—than anywhere else, so the competition is

fierce and the capital to open and maintain a

restaurant is always a critical factor in success

or failure.

Nevertheless, the current media mantra is that

restaurants—even some of the best known—are

dropping like flies because of intimidating,

greedy landlords, of which NYC seems to have no

other kind. People were stunned when places like

Nobu, Carnegie Deli, The Four Seasons, Da Silvano,

Le Périgord, Spice Market, Telepan and Betony

closed, but the reasons vary widely.

Just last week media darling chef Alex

Stupak opened a much grander version of his

Empellón in Midtown at the same time he closed

the original premises that opened in 2011

in the East Village, explaining, "

First, let’s consider that a restaurant lease generally runs about 15 years, sometimes with guarantees of an extension, though not at the same rent. Landlords, bless their black hearts, see their own expenses go up and can’t be blamed for wanting to protect their profits. But, it is reasonable to ask, why would you hike a rent by 400% for a restaurant doing good business and expect the owner to be able to pay?

That was certainly the case with the

great Italian restaurant San Domenico, which ten

years ago balked at a 400% increase and left the

building, which went unoccupied for more than two

years. (Marea

finally moved in and is doing fabulous business.)

So why would a landlord risk losing all that money

for that length of time? The answer is fairly simple

most of the time: a loss is a tax deduction, which

is often more than worthwhile to balance the books

vis-à-vis gross income elsewhere.

That was certainly the case with the

great Italian restaurant San Domenico, which ten

years ago balked at a 400% increase and left the

building, which went unoccupied for more than two

years. (Marea

finally moved in and is doing fabulous business.)

So why would a landlord risk losing all that money

for that length of time? The answer is fairly simple

most of the time: a loss is a tax deduction, which

is often more than worthwhile to balance the books

vis-à-vis gross income elsewhere.

Exorbitant rent hikes happened to La Caravelle, which never re-located, even to the Union Square Café, which took more than a year to re-open on East 19th Street, in larger quarters. The Four Seasons (left) was booted out of its half-century residence in the Seagram Building, not because of rent but because the new owner wanted something different, under another name--The Grill. The partners of the former Four Seasons will open in a nearby location this year.

In Nobu’s case, as partner Drew Nieporent

explained to New York

magazine, “We’ve been there 23 years, and the rent

has accelerated quite a bit. I have customers who

pay money to us, so I understand that without

those people, I can’t be in business. For some

reason, the tenant-landlord relationship is

different. It’s like we pay all that money and are

treated like the scum on someone’s shoe. I just

don’t understand it. But I think our time had

come. The building was fair to us, more or less,

but it wasn’t like at the end they said, `We

really don’t want to lose you.’” Nobu has

re-opened in a much larger space, within a hotel,

with “greater facilities to do what we need to

do.”

Thirteen years ago, the closing of the bellwether classic French restaurant Lutèce, in business for 40 years, but not for lack of business or a rent hike: Chef André Soltner (right) owned the building, so rent was not an issue. Soltner just decided to retire after a lifetime behind the stoves. Yet, then and now, the NYC food media continue to beat the death drum of what Sierra Tishgart of New York calls “this kind of ornate, old-school, romantic French restaurant [that cannot] hold the same allure and survive in New York.”

Here’s a sampling of notable French restaurants that have closed: Alain Ducasse’s Adour, Alain Allegretti’s Bistro La Promenade, Keith McNally’s Pastis, André and Rita Jammet’s La Caravelle, Jean Jacques-Rachou’s La Côte Basque, Jean Michel Bergougnoux’s L’Absinthe, the International Culinary Center’s L’école, Amadeus Broger’s Le Philosophe, David Waltuck and George Stinson’s Élan, Philippe Lajaunie’s Les Halles Brasserie, and Georges Briguet’s Le Périgord.

Let’s look more closely at that list and why the restaurants closed:

• Alain Ducasse did not own Adour and his management contract had run out.

• Allegretti’s Bistro La Promenade was in no way an “ornate, old-school” restaurant; it was a bistro and decorated accordingly. It simply failed to attract enough business. Neither did new restaurants like Le Philosophe and Elan, neither ornate nor old school.

• Nor was L’Absinthe fancy or highfalutin, and it had a very long run for more than a decade.

• L’école was part of what was called the French Culinary Institute as a restaurant to train culinary students. The Institute changed its name to the International Culinary Center and became more global, so a place called L’ecole was not the right fit.

• La

Caravelle did fall victim to a landlord’s

outrageous demands, but that was 13 years

ago—hardly indicative of anything at all.

• La

Caravelle did fall victim to a landlord’s

outrageous demands, but that was 13 years

ago—hardly indicative of anything at all.

• Business at La Côte Basque collapsed after

terrible, very unfair health department inspection

ratings, but

the premises were immediately occupied by

Ducasse’s still-thriving Benoit, which was just

redecorated and still going strong.

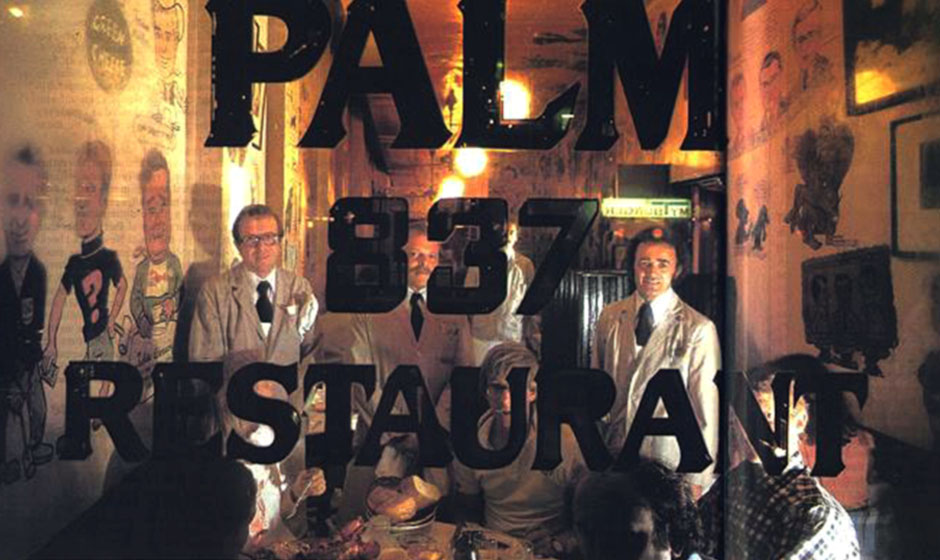

Yet when the original and

legendary Palm steakhouse (opened 1920) on Second

Avenue closed last year because of a landlord

hike, the media did not proclaim high-end

steakhouses were falling out of favor.

Tishgart fails to mention that La Grenouille, Le

Bernardin, and Daniel are still mobbed every

night, and very high-end modern dining rooms

with multi-million dollar interiors, like Eleven

Madison Park, Nomad, Lincoln Ristorante, Gotham

Bar & Grill, Gabriel Kreuther and Per Se are

too. The

hottest place in town this year is Le Coucou, a

fine dining French restaurant in SoHo with white

tablecloths, romantic lighting, and high prices. So,

too, is Vaucluse on the upper East Side, which

owner Michael White calls “a celebration of

the uniquely spirited Provençal joie de vivre,”

serving

escargots, páté en croûte, poulet rôti and canard à

l’orange.

Then there is the question of NYC’s Restaurant Union, Local 100, which is notorious for making it near impossible to run a restaurant while paying dishwashers in excess of $20 an hour. When Tavern on the Green lost its lease (with NYC), it took years before anyone could negotiate a deal with the union, whose bosses couldn’t have cared less if scores of their members lost their jobs. L’Atelier de Joël Robuchon in the midtown Four Seasons Hotel was another union casualty. So, too, after 53 years in business, owner Georges Briguet of Le Périgord faced extra costs of $12,000 more per week if he agreed to union demands. Le Cirque moved out of the Palace Hotel to East 58th Street, where they did not have to hire union workers.

Such examples have nothing to do with “this kind of ornate,

old-school, romantic French restaurant [that

cannot] hold the same

allure and survive in New York.”

Le

Cirque's entering Chapter 11 bankruptcy this

spring was rooted in the usual landlord disputes. I spoke

directly with Marco Maccioni, who explained that

Le Cirque—with nine restaurants worldwide and the

new Dubai Ritz-Carlton just opened, as well as

Doha, Dallas, and Orlando this year—had a cash

flow problem that will be resolved soon. ”We would

not have filed Chapter 11 if we planned to go out

of business. You file it in order to stay in

business,” Maccioni told me. While he said that

business has been off somewhat in NYC (as many

top-end restaurants are reporting), there are no

plans whatsoever to close the doors at Le Cirque.

So much for the sensational story “Is This the

Beginning of the End for Le Cirque?” in, yes, New

York

by (guess who)

Sierra Tishgart.

Le

Cirque's entering Chapter 11 bankruptcy this

spring was rooted in the usual landlord disputes. I spoke

directly with Marco Maccioni, who explained that

Le Cirque—with nine restaurants worldwide and the

new Dubai Ritz-Carlton just opened, as well as

Doha, Dallas, and Orlando this year—had a cash

flow problem that will be resolved soon. ”We would

not have filed Chapter 11 if we planned to go out

of business. You file it in order to stay in

business,” Maccioni told me. While he said that

business has been off somewhat in NYC (as many

top-end restaurants are reporting), there are no

plans whatsoever to close the doors at Le Cirque.

So much for the sensational story “Is This the

Beginning of the End for Le Cirque?” in, yes, New

York

by (guess who)

Sierra Tishgart.

There

are, of course, a plethora of NYC restaurants that

close because they were never properly capitalized

in the first place, so that, despite rave reviews, Michelin

stars and packed houses, they couldn’t survive

the rigors of the restaurant business. TV

celebrity chef Tom Colicchio’s ground-breaking

Craftbar and his Meatpacking District steakhouse

went belly up. Yet, when a much-praised sushi

shop in Bedford Stuyvestant goes under, neither

New York nor any other of

the media bewail that New Yorkers no longer want

to eat sushi.

Restaurants are rarely

opened without investors—to open his first

restaurant, Montrachet, Drew Nieporent borrowed

money from his mother—and investors have to be

paid back out of gross income. Mom-and-Pop

start-ups are a thing of the past. In the case of

Tapestry, owner Suvir Saran told the Times,

high rents and slow traffic caused the place to

close in less than a year. “The

overhead was high, and we had to do two turns a

night and were only doing one.”

The tiny Take Root (right) vegetarian restaurant in Brooklyn’s Carroll Gardens, which earned a Michelin star, closed within four years because its lease ran out. More telling, however, the owners, Anna Hieronimus and Elise Kornack, had from the start decided to be open only three nights a week and serve only 12 guests per night—la dee dah! Do the math.

And don’t for a moment underestimate

the Trump factor; many people refuse to eat in a

Trump building where some of their meal costs will

go to him. Owing to the security block-offs around

Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue and 56th Street many

of the restaurants nearby have been suffering. A

small drop in profits can mean the demise of a

restaurant, which in the best of times may survive

on five to ten percent net profits. Protesters

carrying anti-Trump signs have paraded outside

other Trump buildings. Some entered Jean-Georges

Vongerichten’s restaurant in Trump Tower (left), and

police had to usher them out as guests were paying

for their $58 lunch. Ironically, Vongerichten had

turned down two requests from Trump’s assistants

asking for a reservation the day after he won the

election. “At that point,” said the

chef-restaurateur, “Trump hadn’t dined at my

restaurant in two years—he’s my landlord and I

know him, of course. I told his PA: ‘Maybe not so

soon. There are journalists standing outside my

restaurant now!’"

A third request, with Mitt Romney to be

along, was granted.

And don’t for a moment underestimate

the Trump factor; many people refuse to eat in a

Trump building where some of their meal costs will

go to him. Owing to the security block-offs around

Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue and 56th Street many

of the restaurants nearby have been suffering. A

small drop in profits can mean the demise of a

restaurant, which in the best of times may survive

on five to ten percent net profits. Protesters

carrying anti-Trump signs have paraded outside

other Trump buildings. Some entered Jean-Georges

Vongerichten’s restaurant in Trump Tower (left), and

police had to usher them out as guests were paying

for their $58 lunch. Ironically, Vongerichten had

turned down two requests from Trump’s assistants

asking for a reservation the day after he won the

election. “At that point,” said the

chef-restaurateur, “Trump hadn’t dined at my

restaurant in two years—he’s my landlord and I

know him, of course. I told his PA: ‘Maybe not so

soon. There are journalists standing outside my

restaurant now!’"

A third request, with Mitt Romney to be

along, was granted.

The way the new math adds up, one

of the best options for an established

restaurateur is to sign a management contract with

a hotel trying to establish its credentials and

distinguish itself from the pack in NYC. In such

cases restaurants, like Wolfgang Puck’s CUT in the

downtown Four

Seasons, Tom Colicchio’s Fowler & Wells and

Keith McNally’s Augustine, both in the Beekman,

and Stephen Starr’s much praised Le Coucou (right) in

Hotel 11, opening cost them a fraction of what it

would have cost if they did it all on their own. Costs

for design, kitchen equipment, glass and

silverware, staff outfits and the like are all

absorbed by the hotel, in most cases. And, if

the restaurant flops or founders—as happened when

Jonathan Waxman’s JAMS in 1 Hotel Central Park got

deadly reviews—the restaurant either stays open

out of convenience for hotel guests or it changes

into “a new concept” when the contract ends. Or

the celebrity chef is sent packing, as when Scott

Conant exited Faustina in the Cooper Square Hotel

after weak reviews and poor business.

Photo

by Michael Breton

Four

Seasons, Tom Colicchio’s Fowler & Wells and

Keith McNally’s Augustine, both in the Beekman,

and Stephen Starr’s much praised Le Coucou (right) in

Hotel 11, opening cost them a fraction of what it

would have cost if they did it all on their own. Costs

for design, kitchen equipment, glass and

silverware, staff outfits and the like are all

absorbed by the hotel, in most cases. And, if

the restaurant flops or founders—as happened when

Jonathan Waxman’s JAMS in 1 Hotel Central Park got

deadly reviews—the restaurant either stays open

out of convenience for hotel guests or it changes

into “a new concept” when the contract ends. Or

the celebrity chef is sent packing, as when Scott

Conant exited Faustina in the Cooper Square Hotel

after weak reviews and poor business.

Photo

by Michael Breton

So there are plenty of reasons NYC restaurants close, and while almost all have to do with money and the fact that costs for everything are higher in NYC, restaurateurs all around the country fight the same battles. But to suggest that any particular kind of restaurant—haute cuisine French, high-end Italian, expense account Japanese—closes because it is out of fashion or not trendy is to completely misunderstand the complexity of the business. And when all the eateries on the Lower East Side and in Brooklyn shutter their graffiti-scarred corrugated metal gates, the $100-a-person steakhouses and the $150-per-person French restaurants and the white truffle-rich Italian restaurants in midtown will still be flourishing.

There’s a lifetime for everything, especially restaurants, and staying open for the length of one’s lease is pretty damn impressive.

RUFFINO

CELEBRATES

RUFFINO

CELEBRATES 140 YEARS OF CHIANTI

More than once I’ve been asked, if I could drink only one wine, what would it be? Assuming the query does not mean the last wine before the firing squad (that would be a double magnum of Romanée-Conti), I answer as if I were going to be stranded on a deserted island for a long time, in which instance, the wine I would hope might wash up on shore would be a case of Chianti Classico from a fine producer like Ruffino.

For, although Chianti may not be the best match

for the fish that  swim

around my little island, it is without doubt one

of the most versatile wines in the world, with a

generous balance of fruit and acid and a

characteristic earthiness underpinning its light

tannins.

swim

around my little island, it is without doubt one

of the most versatile wines in the world, with a

generous balance of fruit and acid and a

characteristic earthiness underpinning its light

tannins.

Chianti used to be so simple. It was the pizza wine you bought in a green bottle in a straw (later plastic) basket called a fiasco. Even if it wasn’t all that good, you could always use the bottle afterwards as a candleholder.

It was the wine on the table of every movie scene set in an Italian restaurant, even the romantic dogs’ dinner in “Lady and the Tramp.” But that plonky image has been outdated for quite some time.

Starting in the 1970s, well-heeled, market savvy producers like Ruffino, Antinori and Frescobaldi upgraded not just their own image but that of all Chiantis in Tuscany, helping the entire region obtain the prestigious D.O.C.G. appellation from the Italian government in 1996, guaranteeing high quality along with strict standards for making the wines. The Classico regional consortium, founded in 1924 with 33 members, now has more than 600 producers.

Chianti Classico must now be made with a minimum of 80 percent Sangiovese grapes, based on modern, healthier clones, with up to 20 percent other grapes allowed. Beginning in 2005 the long tradition of blending in inferior Trebbiano and Malvasia grapes was no longer permitted. Also, the old “governo” process, by which unfermented grape juice is added to young wines to restart fermentation in order to make the wines marketable at an earlier date, is now very rarely done anywhere.

Today Chiantis are fuller, richer, with more alcohol. Still, they have not been able to achieve the reputation of other Sangiovese-based Tuscan wines like Brunello di Montalcino, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, and, increasinlgy, Chianti Classico.

“The so-called ‘Super Tuscans’ pushed Chianti aside in the 1980s,” says Gabriele Tacconi, Chief Winemaker at Ruffino, referring to the wholly unofficial marketing term for the region’s red wines not made according to the D.O.C.G. rules. “It’s my job to put us on an equal footing with wines like Sassicaia and Ornellaia, which use a lot of Cabernet Sauvignon. But in the higher altitudes of the Chianti region, except for Bolgheri, you should be careful in using Cabernet.” (Ruffino has made its own highly regarded “Super Tuscan,” named Modus, since 1997.)

I spoke

with Tacconi (left)

in New York at The Modern restaurant over a dinner

that was decidedly not Italian—warm foie gras

tart, white asparagus with trout roe, lamb with

Israeli couscous—but the Ruffino wines showed very

well, including a remarkably youthful Riserva

Ducale Oro 1999 vintage of enormous charm and a

2005 Greppone Mazzi di Brunello di Montalcino with

interesting licorice notes.

I spoke

with Tacconi (left)

in New York at The Modern restaurant over a dinner

that was decidedly not Italian—warm foie gras

tart, white asparagus with trout roe, lamb with

Israeli couscous—but the Ruffino wines showed very

well, including a remarkably youthful Riserva

Ducale Oro 1999 vintage of enormous charm and a

2005 Greppone Mazzi di Brunello di Montalcino with

interesting licorice notes.

Tacconi, who speaks impeccable English, told me

2017 is the 140th anniversary of Ruffino, founded

by Leopoldo and Ilario Ruffino, and he is only the

estate’s third winemaker. This is

also the 90th anniversary of the iconic Riserva

Ducale and the 70th anniversary of Riserva Ducale

Oro (Gold Label).

The name derives from when, in 1890, the

Duke of Aosta was so impressed by the Ruffino

wines that he appointed the estate as the official

supplier to the Italian royal family; in 1927

Ruffino returned the honor by naming their best

wine Riserva Ducale. In time Ruffino became the

first Chianti imported into the U.S.; they began

making wines in the Chianti Classico region

after World War II. The Gold Label was awarded Gran

Selezione status with the 2010 vintage.

region

after World War II. The Gold Label was awarded Gran

Selezione status with the 2010 vintage.

Tacconi has been working hard to improve the estate year after year, with the most modern enological means, which include using GPS to track the vigor of the plantings in the six vineyards within the company. At the Poggio Casciano estate, an underground barrique tunnel connects the villa with the newer winery buildings, where extensive soil and climate research is performed to find the best clones to fit the individual terroirs, such as Gretole (left), whose name refers to galestro rock that gives a particular taste to Sangiovese. At the hilly Solatia (“sun-bathed”), Chardonnay finds an amenable home.

Oddly

enough, Tacconi is actually from Modena, in

Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region, and he joked, “When

you don’t turn your head when a Ferrari goes by,

it means you’re from Modena,” referring to the

auto manufacturer’s headquarters in that city. In

addition, he’s married to an American woman,

Tasha, from Westchester County, NY.

Oddly

enough, Tacconi is actually from Modena, in

Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region, and he joked, “When

you don’t turn your head when a Ferrari goes by,

it means you’re from Modena,” referring to the

auto manufacturer’s headquarters in that city. In

addition, he’s married to an American woman,

Tasha, from Westchester County, NY.

“I have 140 years of winemaking evolution to respect at Ruffino,” says Tacconi, now working at the winery for nineteen years, becoming chief winemaker in 2008. “We have always aimed for elegance in our wines, and although picking our grapes by hand may seem romantic these days, it is still the way to find the best, healthiest grapes among the rest. Sangiovese must be picked within two weeks, or else the alcohol will go too high. That is part of my aim to give the wines a restraint and a finesse that does not overpower all the components of the wine.”

After enjoying the wine, the food and the conversation that evening, it occurred to me that if a case of Ruffino does come ashore on my desert island, I can only hope that it’s being carried by Gabriele Tacconi, with grape vine in his pocket.

FOOD WRITING 101: DO

NOT USE IMAGERY

FOOD WRITING 101: DO

NOT USE IMAGERY

❖❖❖

Sponsored by Banfi Vintners

SPRING

IS HERE AND SO ARE WONDERFUL CHILEAN

WINES

As Summer finally kicks into

gear, we are reminded of the fragility of Mother

Earth and her bounty. As an importer

representing several family wine makers from around

the globe, I often like to point out that all the

wines that we represent are green, some of them

greener than others. The greenest of all are

classified as Biodynamic or certified Organic.

One of the most interesting selections of

eco-balanced, organic and biodynamic wines comes to

us from Chile and the vineyards of Emiliana (left).

As Summer finally kicks into

gear, we are reminded of the fragility of Mother

Earth and her bounty. As an importer

representing several family wine makers from around

the globe, I often like to point out that all the

wines that we represent are green, some of them

greener than others. The greenest of all are

classified as Biodynamic or certified Organic.

One of the most interesting selections of

eco-balanced, organic and biodynamic wines comes to

us from Chile and the vineyards of Emiliana (left).

Emiliana was founded by our

friends, the Guilisasti family, who have a long and

proud history of winemaking with their Concha y Toro

brand. Three decades ago, well ahead of the

curve that has made organic wines all the rage

today, they set up dedicated and, most important for

organic farming, isolated vineyards for this type of

agriculture. Many may picture the small farmer

as being the most “organic,” but in the reality of

our wine world, sometimes it takes the “big guys” to

act as a locomotive to get a movement such as this

on track.

Organic farming is a

form of agriculture which avoids or largely excludes

the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides,

plant growth regulators, and livestock feed

additives.

Organic

farmers rely on crop rotation, crop residues, animal

manures--including llamas--and mechanical

cultivation to maintain soils productivity and

health, to supply plant nutrients, and to control

weeds, insects and other pests. To call a wine

organic in the US, government regulation says that

it must be produced from 95% organically grown

ingredients with no added sulfites. If you add

sulfites in the relatively minimal amount of 100

parts per million, you can only say that the wine is

“made from organically grown grapes.” Now, not

to go into a chemistry lesson, but it is virtually

impossible to make a wine without that modest dose

of sulfites, at least if you want to drink it beyond

ten feet of the cellar it was made in and wish it to

survive any moderate amount of aging.

Biodynamic farming

adheres to the same principles, but takes it one

step further by relying on the cycles of the moon

and the sun to dictate much of what is done in the

field, and uses animal treatments such as compost

teas, horns buried with fertilizer, deer bladders, etc., to

treat the soil. It may sound a little hocus

pocus, but in reality it is very comparable to

homeopathic medicine, using the body’s (in this

case, the earth’s) own energy to heal

itself.

Emiliana has four distinct

collections of lovingly crafted organic wine now

available in the US – the base line of Natura, the

next step up in Novas, a stand-alone wine in Coyam,

and the ne-plus-ultra of bio-dynamic wines,

Ge. One taste of any of these and you too may

find yourself turning green – not with envy, but for

a newfound love of organic winemaking!

Recommended – green wines for Spring:

Natura Chardonnay In the cool coastal Pacific

climate of the Casablanca Valley, organically grown

grapes are hand picked during the last week of

March, and vinified in stainless steel tanks, free

of the domineering influence of oak. On the

nose, tantalizing citrus aromas of grapefruit and

lime blend with notes of pineapple, all of which

reappear on the palate and finish with balance

thanks to the wine’s freshness and natural

acidity. Delicious with spring salads and

seafood dishes.

Natura Carmenere – From the rustic

isolation of the Colchagua Valley, this intense and

voluptuous offers aromas of cherries, chocolate and

spice, coming together in ramped up volume on the

palate with soft, round tannins and firm,

well-balanced structure. Great balance between

fruit and oak, with a long, juicy finish.

Novas Sauvignon Blanc

Gran Reserva – Hailing from the San Antonio Valley’s thin

rocky and clay soils, the organic grapes for this

wine are harvested by hand in March and undergo

fermentation in stainless steel to preserve their

bright fruit character. Herbal notes mixed

with citrus and soft floral hints fill the bouquet;

the taste is medium bodied with grapefruit flavors

joined by a delicate acidity and a touch of

minerality.

Novas Pinot Noir Gran

Reserva – The grapes for this wine are grown in the

cool, coastal Casablanca Valley’s permeable sandy

loam soils, and harvested by hand. After a

cold soak on the skins, the wine is aged for 8

months in French oak barrels to add character, depth

and roundness.

Bright ruby red in color with attractive

aromas of berries, strawberries and notes of spice

and cocoa, this wine bursts with fruit flavor,

layered with earthiness. Delicious with white meats,

light sauces, full flavored fish and shellfish,

cured ham and sushi.

Coyam – A blend dominated by Syrah

with nearly equal parts of Carmenere and Merlot

balanced by “soupcons” of Cabernet Sauvignon,

Mourvedre and Petit Verdot, from the Colchagua

Valley estate called Los Robles – Spanish for

the oaks, called “Coyam” by the native Mapuche

people in their own language. Hand harvested

certified biodynamic grapes are naturally fermented

in French oak barrels. Coyam is largely

unfiltered and aged for 13 months in barrels.

Aromas of ripe red and black fruits integrate with

notes of spice, earth and a hint of vanilla

bean. Elegant expressions of fruit are

delicately interwoven with oak, mineral and toffee.

Coyam – A blend dominated by Syrah

with nearly equal parts of Carmenere and Merlot

balanced by “soupcons” of Cabernet Sauvignon,

Mourvedre and Petit Verdot, from the Colchagua

Valley estate called Los Robles – Spanish for

the oaks, called “Coyam” by the native Mapuche

people in their own language. Hand harvested

certified biodynamic grapes are naturally fermented

in French oak barrels. Coyam is largely

unfiltered and aged for 13 months in barrels.

Aromas of ripe red and black fruits integrate with

notes of spice, earth and a hint of vanilla

bean. Elegant expressions of fruit are

delicately interwoven with oak, mineral and toffee.

Ge – Chile’s first certified

biodynamic wine, the name Ge is a nod to Geos, the

earthly environment pulling together all the

elements that surround us. Ge is a blend of

nearly equal parts of Syrah, Carmenere and Cabernet

Sauvignon grown in the deep soils of colluvial

origin in the coastal range, which lends mineral

complexity. Naturally fermented in oak barrels, Ge

is deep plum red with violet tones; it offers

intense aromas of black fruits and berries alongside

mineral notes and a soft touch of tobacco

leaf. Generously fruity with cedar notes, Ge

is well balanced with tremendous volume, well

rounded tannins and a long finish.

For more information please visit http://www.banfiwines.com/winery/emiliana/

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The

Hound in Heaven (21st Century Lion Books)

is a novella, and for anyone who loves dogs,

Christmas, romance, inspiration, even the supernatural, I

hope you'll find this to be a treasured favorite.

The story concerns how, after a New England teacher,

his wife and their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found

in their barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of

promise. But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog

Lazarus and the spirit of Christmas are the only things

that may bring his master back from the edge of

despair.

The

Hound in Heaven (21st Century Lion Books)

is a novella, and for anyone who loves dogs,

Christmas, romance, inspiration, even the supernatural, I

hope you'll find this to be a treasured favorite.

The story concerns how, after a New England teacher,

his wife and their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found

in their barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of

promise. But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog

Lazarus and the spirit of Christmas are the only things

that may bring his master back from the edge of

despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las Vegas

JOHN CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas

food and restaurant scene since 1995. He is

the co-author of EATING LAS VEGAS – The 50

Essential Restaurants (as well as

the author of the Eating Las Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

Eating Las Vegas

JOHN CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas

food and restaurant scene since 1995. He is

the co-author of EATING LAS VEGAS – The 50

Essential Restaurants (as well as

the author of the Eating Las Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Editor/Publisher: John

Mariani.

Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani,

Robert Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Geoff Kalish, Mort

Hochstein, and

Brian Freedman. Contributing Photographers: Galina

Dargery. Technical Advisor: Gerry McLoughlin.

To un-subscribe from this newsletter,click here.

© copyright John Mariani 2017