MARIANI’S

Virtual Gourmet

April

12, 2020

NEWSLETTER

❖❖❖

IN THIS ISSUE

IF YOU CAN'T TRAVEL NOW, HERE ARE SOME OF

THE BEST TRAVEL BOOKS FOR A HOUSEBOUND READER

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

LOVE AND PIZZA

Chapter Three

By John Mariani

BELOVED ITALIAN-AMERICAN

RESTAURATEUR PASSES AWAY

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

DOMAINE BOUSQUET WINES OF ARGENTINA

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

IF YOU CAN'T TRAVEL NOW, HERE ARE SOME OF

THE BEST TRAVEL BOOKS FOR A HOUSEBOUND READER

By John Mariani

End Papers of The Book of Knowledge

As

every travel writer and editor knows, most

people who read books and magazine articles

about far-flung or even close-by places to visit

never actually do. They might well pack a

guidebook in their luggage to consult for the

age of Rome’s Pantheon or the height of the

Eiffel Tower or where to find a fried chicken

dinner house in Omaha, but the more exotic a

place is the less likely people are to get

there. The authors of the best travel books,

therefore, do not seek to mark out routes, give

hotel prices or locations of spice bazaars but

instead try to give a thrilling panorama on the

culture and natural beauty of a place and what

makes it unique from others. And they do it

without the advantage of an expense account.

So, at a time when travel is

effectively prohibited, here are some of the

best books written by the best authors for the

housebound armchair traveler.

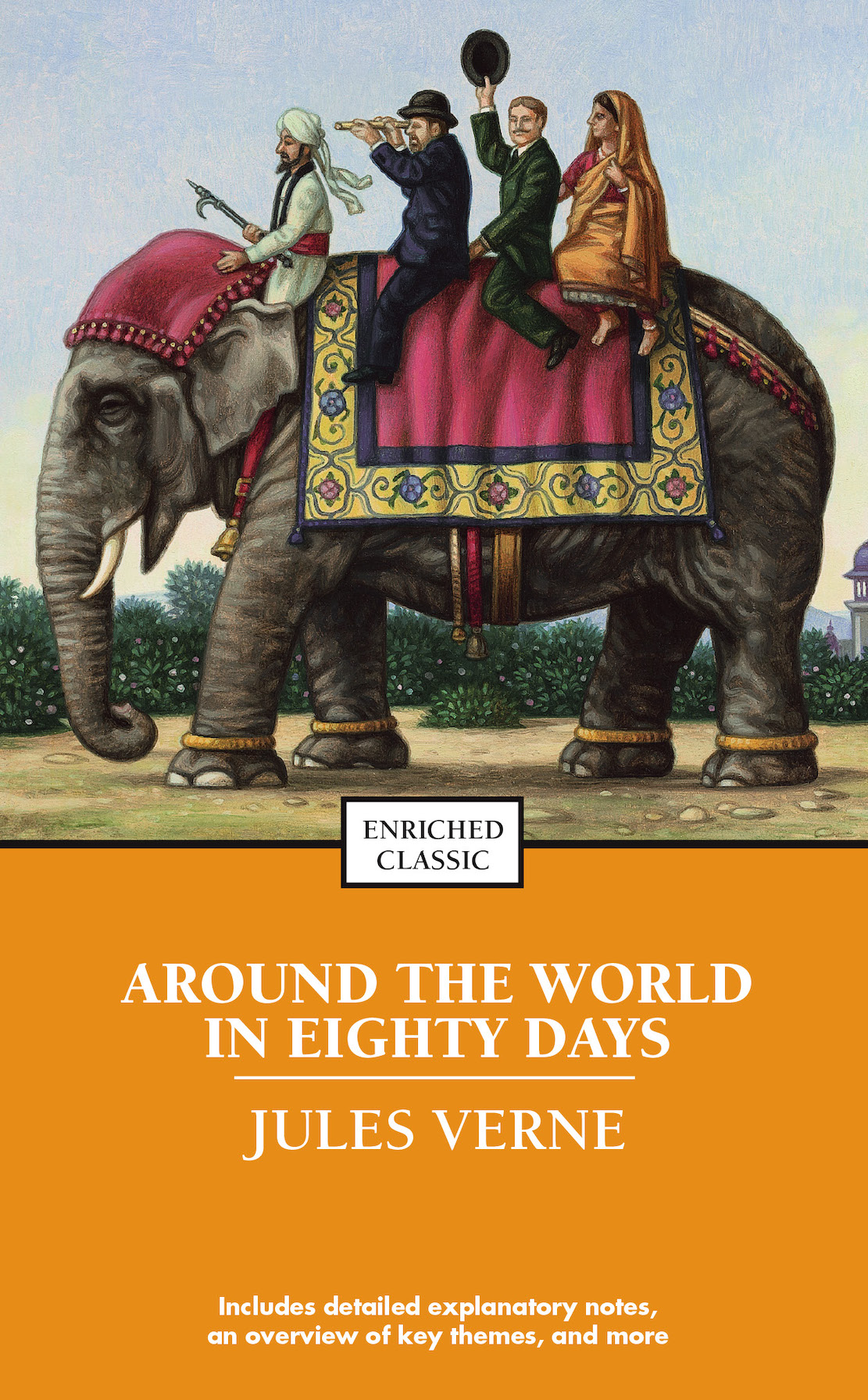

Around

the World in Eighty Days (1872) by Jules Verne—Although

the enchanting movie made from Verne’s novel is

now more famous, upon publication the original had

been an international bestseller and Verne’s most

popular book.

Verne himself had never actually

circumnavigated the world—he left France only once

to sail around Europe—instead using his

imagination and research to produce science

fiction stories along with Eighty Days,

which was filled with headlong adventures by

Phineas Fogg from London to Suez, Bombay, Hong

Kong, Yokohama, San Francisco and New York, all to

win a small wager with his British club members. The

book is a fantasy of another time but gets to the

heart of what stimulates all human beings’ desire

to travel well beyond their safe zones. It also

demonstrates the technological triumphs of Verne’s

age, including America’s Transcontinental Railway,

the integration of India’s railroads and the

opening of the Suez Canal, three years earlier. As

a Frenchman, Verne could not help himself from

writing of his British hero, “As for seeing the town,

the idea never occurred to him, for he was the

sort of

Around

the World in Eighty Days (1872) by Jules Verne—Although

the enchanting movie made from Verne’s novel is

now more famous, upon publication the original had

been an international bestseller and Verne’s most

popular book.

Verne himself had never actually

circumnavigated the world—he left France only once

to sail around Europe—instead using his

imagination and research to produce science

fiction stories along with Eighty Days,

which was filled with headlong adventures by

Phineas Fogg from London to Suez, Bombay, Hong

Kong, Yokohama, San Francisco and New York, all to

win a small wager with his British club members. The

book is a fantasy of another time but gets to the

heart of what stimulates all human beings’ desire

to travel well beyond their safe zones. It also

demonstrates the technological triumphs of Verne’s

age, including America’s Transcontinental Railway,

the integration of India’s railroads and the

opening of the Suez Canal, three years earlier. As

a Frenchman, Verne could not help himself from

writing of his British hero, “As for seeing the town,

the idea never occurred to him, for he was the

sort of  Englishman who, on his

travels, gets his servant to do his sightseeing

for him.”

Englishman who, on his

travels, gets his servant to do his sightseeing

for him.”

Stories of Hawaii

by Jack London—This is a collection of many

stories London wrote during three long stays in

the Hawaiian islands—1907, 1915 and 1916—which he

loved at least as much as he did the Yukon

territory he made famous in books like The Call of

the Wild and White Fang.

In stories both heartwarming and tragic, with

enticing names like “On the Makaloa Mat,” “The

Tears of the Ah Kim” and “The Bones of Kahekili,”

the reader finds a wide-ranging gallery of

characters, both native and not, and of how the

islands had been impacted by immigrants and

developers. London’s prose, often regarded as

robust and sinewy, can be exotically beautiful

here, as when he writes of the “lofty Koolau

Mountains’s trade winds” as “soft breathings,

[when] the air grew heavy and balmy with perfume

of flowers and exhalations of fat, living soil.”

A

Moveable Feast (1964) by Ernest Hemingway—Hemingway

did not invent Paris, but he created both

fictional and non-fictional narratives about the

city that have became indelible, not least in A Moveable

Feast, a posthumous memoir about his

expatriate life in Paris with his wife Hadley,

“when we were very poor and very happy.” Ever

since its publication (as well that of The Sun Also

Rises and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”)

travelers have viewed Paris through Hemingway’s

eyes and descriptions: the food and drink at the

brasseries like Les Cloiserie des Lilas (his

favorite), Café du Dôme and Lipp; the “false

spring” when he went to the Saint-Cloud race

track; autumn in the Luxembourg Gardens; the

market street of Rue Mouffetard, where he bought

mandarin oranges and chestnuts to nibble while he

wrote. In those memories Hemingway crystallized

the romance of a city as he

A

Moveable Feast (1964) by Ernest Hemingway—Hemingway

did not invent Paris, but he created both

fictional and non-fictional narratives about the

city that have became indelible, not least in A Moveable

Feast, a posthumous memoir about his

expatriate life in Paris with his wife Hadley,

“when we were very poor and very happy.” Ever

since its publication (as well that of The Sun Also

Rises and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”)

travelers have viewed Paris through Hemingway’s

eyes and descriptions: the food and drink at the

brasseries like Les Cloiserie des Lilas (his

favorite), Café du Dôme and Lipp; the “false

spring” when he went to the Saint-Cloud race

track; autumn in the Luxembourg Gardens; the

market street of Rue Mouffetard, where he bought

mandarin oranges and chestnuts to nibble while he

wrote. In those memories Hemingway crystallized

the romance of a city as he knew it and how we all wish to see

and taste it.

knew it and how we all wish to see

and taste it.

On the Road (1957) by Jack Kerouac—If Kerouac

needed anything it was to be restrained and edited

into an approachable form. The man just rambles on

and on. But he did so with a fresh, marvelous

open-eyed style that redeemed the old pioneer

notion that an American’s birthright is to follow

where the road may lead him, even after the west

was conquered and the Pacific Ocean was the

country’s limit. Like his companion Neal Cassady

(Dean Moriarty in the novel), Kerouac had a soul

“wrapped up in a fast car, a coast to reach, and a

woman at the end of the road.” It is the rare

American of the last century who has been immune

to that allure.

Travels

with Charley (1962) by John Steinbeck—Based on a

10,000-mile 1960 cross-country trip Steinbeck took

with his dog Charley in a camper named Rocinante,

this rambling memoir gives us the author’s take on

everything from eating lobster in Maine to a

Thanksgiving Day “orgy” in Amarillo. He travels

I-10, remarking on the imagination it took to

build an Interstate highway system for national

defense; of the great California redwoods, saying,

"The vainest, most

slap-happy and irreverent of men, in the

presence of redwoods, goes under a spell of

wonder and respect"; and saying his goodbyes to

the territories of his childhood, climbing

Fremont Peak and driving through his beloved

Salinas Valley. Written at a time of troubling

change in America, Steinbeck wrote of those he

encountered, “I

saw in their eyes something I was to see over

and over in every part of the nation—a burning

desire to go, to move, to get under way,

anyplace, away from any Here. They spoke quietly

of how they wanted to

Travels

with Charley (1962) by John Steinbeck—Based on a

10,000-mile 1960 cross-country trip Steinbeck took

with his dog Charley in a camper named Rocinante,

this rambling memoir gives us the author’s take on

everything from eating lobster in Maine to a

Thanksgiving Day “orgy” in Amarillo. He travels

I-10, remarking on the imagination it took to

build an Interstate highway system for national

defense; of the great California redwoods, saying,

"The vainest, most

slap-happy and irreverent of men, in the

presence of redwoods, goes under a spell of

wonder and respect"; and saying his goodbyes to

the territories of his childhood, climbing

Fremont Peak and driving through his beloved

Salinas Valley. Written at a time of troubling

change in America, Steinbeck wrote of those he

encountered, “I

saw in their eyes something I was to see over

and over in every part of the nation—a burning

desire to go, to move, to get under way,

anyplace, away from any Here. They spoke quietly

of how they wanted to go someday, to move

about, free and unanchored, not toward something

but away from something. I saw this look and

heard this yearning everywhere in every state I

visited. Nearly every American hungers to

move.”

go someday, to move

about, free and unanchored, not toward something

but away from something. I saw this look and

heard this yearning everywhere in every state I

visited. Nearly every American hungers to

move.”

The Great Railway Bazaar

(1975) by Paul Theroux—Written along what

was called the post-Beatles “hippie trail” to

India, this was a very new and different kind of

travel book in that it did not glamorize the

varnished wonders of all he saw but instead gave

an accurate portrait of the poverty, post-colonial

psyche of India and the travails of Asian trains.

He returned to Europe on the Trans-Iberian

Railway, but little of his four-month journey in

1973 was romantic in the traditional sense of

travel literature and therefore gives a truer

picture of the deprivations a wanderer should

expect. “Anything is

possible on a train,” he wrote, “ a great meal,

a binge, a visit from card players, an intrigue,

a good night's sleep, and strangers' monologues

framed like Russian short stories. . . . All

travel is circular. I had been jerked through

Asia, making a parabola on one of the planet's

hemispheres. After all, the grand tour is just

the inspired man's way of heading home. ”

A Year in Provence (1989) by Peter Mayle—At first

intended as a novel, which never got written, all

but ignored by the critics upon publication and

rejected by every French publisher, this little paperback went

on to sell six million copies around the world. Mayle

wryly reported on about the trials and

tribulations, joys and discoveries, tastes and

smells of spending a year restoring a house with

the help and opposition of local farmers, lawyers,

unsavory builders and

a clarinet-playing plumber. The book was a

sensation as an invitation to a somewhat harried

rustic life among genuine eccentrics, and it

clicked in the hearts of both those who’d like

to take a shot at such a life and those who

could only dream of it. Despite many of Mayle’s

characterizations of the provincial French as

derogatory, come dinner time he said they “display the most

sympathetic side of their nature. Tell them

stories of physical injury or financial ruin and

they will either laugh or commiserate politely.

But tell them you are facing gastronomic

hardship, and they will move heaven and earth

and even restaurant tables to help you.”

What Mayle did for Provence, Frances Mayes would

do for Tuscany in her memoir Under the

Tuscan Sun

seven years later, not least to

push up the prices for even the shabbiest of

villas in that northern Italian region.

A Year in Provence (1989) by Peter Mayle—At first

intended as a novel, which never got written, all

but ignored by the critics upon publication and

rejected by every French publisher, this little paperback went

on to sell six million copies around the world. Mayle

wryly reported on about the trials and

tribulations, joys and discoveries, tastes and

smells of spending a year restoring a house with

the help and opposition of local farmers, lawyers,

unsavory builders and

a clarinet-playing plumber. The book was a

sensation as an invitation to a somewhat harried

rustic life among genuine eccentrics, and it

clicked in the hearts of both those who’d like

to take a shot at such a life and those who

could only dream of it. Despite many of Mayle’s

characterizations of the provincial French as

derogatory, come dinner time he said they “display the most

sympathetic side of their nature. Tell them

stories of physical injury or financial ruin and

they will either laugh or commiserate politely.

But tell them you are facing gastronomic

hardship, and they will move heaven and earth

and even restaurant tables to help you.”

What Mayle did for Provence, Frances Mayes would

do for Tuscany in her memoir Under the

Tuscan Sun

seven years later, not least to

push up the prices for even the shabbiest of

villas in that northern Italian region.

Iberia (1968) by James A.

Michener—Michener’s thousand-page novels like Hawaii, Centennial

and Space were

all based on extensive research going back and

forth in historical time as a background for the

fiction. Iberia

was one of his non-fiction door stoppers,

coming in at 818 pages, and what it lacked in

Hemingway’s style and insight about Spain it made

up for in detail, with each of thirteen chapters

focused on a region. He is particularly savvy

about Spanish food, describing, for example, a

platter of 21 entremes,

which were only the beginning of a four-course

meal to follow. As he observed, “To travel across Spain

and finally to reach Barcelona is like drinking

a respectable red wine and finishing up with a

bottle of champagne”—which seems just as true

today as when Michener wrote it.

Blue Highways (1982) by William Least Heat

Moon—The title

refers to the secondary, blue-colored roads on

Rand McNally maps away from the Interstate

highways, which William Least Heat Moon traveled

after separating from his wife and his job. By

staying away from the cities, the author found the

rural American character can be quite different

from that of urban populations. His rule of the

blue road was, “Be careful going in search of

adventure—it’s ridiculously easy to find.”

❖❖❖

To read previous chapters go to archive (beginning with March 29, 2020, issue.

By John Mariani

Cover Art by Galina Dargery

CHAPTER THREE

Nicola

Santini loved Columbia University, with its

campus dominating Morningside Heights and

straddling its way up, down and across

Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue to 120th Street. She

felt a personal pride in the fact that the

campus architecture was done in the Italian

Renaissance style, dominated by the

neo-classical Low Library, whose

hundred-foot-tall dome paid homage to Rome’s

Pantheon.

It was a sober, classic style, in

deliberate contrast to the Neo-Gothic

architecture of Yale and Princeton and the

Georgian brick of Harvard. Nicola was equally

proud that she was among those second- and

third-generation Italians from the Bronx who

were accepted at the Ivy League school, and

she was sure that when her genius brother

Tommy graduated from Bronx High School of

Science, he would have his pick of any

university he wished to attend. Nicola

relished the musty smell in the halls of

academia, the echoes of voices and footsteps

in rooms with such high ceilings, even the

cigarette and pipe smoke that lingered in the

student lounge at Hamilton Hall and behind the

massive oak doors of every professor’s office.

In

her first semester at Columbia, Nicola nursed

a slight inferiority complex, believing that

her fellow students might be far more

accomplished than she was, better traveled,

from wealthier neighborhoods than her own. Also,

the fact that she was a day student did not

engage her much with those who lived on

campus, and she deliberately chose not to join

one of the sororities, sensing that her

background might preclude her and that her

slight Bronx accent might cause other students

to wink at each other.

In

her first semester at Columbia, Nicola nursed

a slight inferiority complex, believing that

her fellow students might be far more

accomplished than she was, better traveled,

from wealthier neighborhoods than her own. Also,

the fact that she was a day student did not

engage her much with those who lived on

campus, and she deliberately chose not to join

one of the sororities, sensing that her

background might preclude her and that her

slight Bronx accent might cause other students

to wink at each other.

In

Belmont, where just about everyone was

Italian, she had never endured a single act of

bigotry—except that the older Italians

constantly made cracks about neighbors who

came from different provinces in the Old

Country.

The Calabrians complained about the

Neapolitans and the Neapolitans about the

Sicilians, and everyone complained about the

influx of Albanians and Croatians. But, out in

the wider world of Columbia, Nicola waited for

bigotry to rear its head. In

her first semester she even tried to modulate

her effusive hand movements and keep her

temper in tow, always eager for a serious

argument about art or religion or politics but

careful not to show too much of her Italian

streak of frustration when confronted by

someone she thought was being a total idiot. Biting

her tongue did not come easily to Nicola

Santini.

By the end of her freshman year,

however, there had been no such bigoted

incidents, other than having to respond again

and again to those naïve enough to ask her,

“So, up where you live, do you know, like,

Mafia guys?”

Nicola hated the question, which seemed

inevitable upon meeting non-Italians, and she

forced herself to hold in a desire to return

such slurs in kind, especially towards the

WASPs. What

she wanted

to say to them was, “You know, while my people

were creating the Renaissance, yours were

still painting their faces blue and worshiping

trees.”

Instead, she’d raise her eyes, shake

her beautiful head, and say, “I really thought

you were smarter than to ask such a dumb

question.”

Belmont had, of course, a not

undeserved reputation as a place where

wiseguys once did business in their so-called

sports clubs, drinking endless cups of sweet

espresso and extorting everyone else. Nicola

knew

a few of the younger assholes trying to wedge

themselves into the mob, and she treated them

with utter contempt as morons more in

imitation of Hollywood stereotypes about

Italians than as men of dubious local honor.

Arthur Avenue at 187th Street

But by the ‘80s the

mob influence had faded, not least because few

of the wiseguys even lived in the neighborhood

any longer, moving instead to big houses in

Westchester, on Long Island, or in New Jersey,

only coming back to the old neighborhood

regularly to eat the kind of Italian-American

food they couldn’t find in towns with names

like Hartsdale, Hicksville and

Hackensack—ricotta-stuffed manicotti,

wine-splashed shrimp scampi and crisply fried

scungilli served at Bella Napoli, where,

occasionally, Nicola would help out as a

hostess on weekends to make money for

tuition.

Having been nurtured on her mother’s

and grandmother’s cooking, Nicola regarded

Bella Napoli’s food as no better than standard

Italian-American fare, with a huge menu

listing the usual baked ziti, lasagna, veal

parmigiana, and spaghetti and meatballs, all

of it lavished with the same marinara sauce

kept simmering in a large pot on the back of

the stove all day. Neither

did she care for the way so much of the food

was prepped far in advance, and she knew the

ingredients used could be of better quality,

especially since the restaurant sat right on a

street lined with good meat, seafood, bread,

vegetable and fruit markets. (Her

brother

Tony swore he’d change all that if he ever got

to buy the place.)

But she had no issue

with Bella Napoli’s pizza, which was widely

considered one of the best in the

neighborhood.

In fact, the New York Daily

News pronounced its  margherita pie the best in the

five boroughs, which resulted in the

restaurant’s owner, Joe Bastone, receiving a

wooden and brass plaque saying just that,

which he proudly hung on a fake brick wall

otherwise covered with signed black-and-white

photos of celebrities eating his glorious

tomato-mozzarella-basil-topped pizza with a

perfectly charred and bubbly crust that was

both crisp and chewy in all the right places.

margherita pie the best in the

five boroughs, which resulted in the

restaurant’s owner, Joe Bastone, receiving a

wooden and brass plaque saying just that,

which he proudly hung on a fake brick wall

otherwise covered with signed black-and-white

photos of celebrities eating his glorious

tomato-mozzarella-basil-topped pizza with a

perfectly charred and bubbly crust that was

both crisp and chewy in all the right places.

Joe had photos of dozens of

the Yankees—the Bronx Bombers’ Stadium was

just a fly ball away on 161st Street—Rizzuto,

DiMaggio, Mantle, Maris, as well as every

politician going after the Bronx vote—a

smiling Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a

squinting Mayor Ed Koch—as well as

Italian-American movie stars and singers like

Tony Bennett, Julius LaRosa, Vic Damone, Alan

Alda, Robert DeNiro, Ben Gazzara, Connie

Francis, and, of course, Dion DiMucci, lead

singer for the Belmonts. “I

swear to God,” Joe would say, “I served that

skinny kid enough damn pizza to sink the Andrea

Doria!”

But

Joe always regretted he could never get

Sinatra to come to Bella Napoli, despite

numerous promises by neighborhood bullshitters

who swore they knew him and would bring him

by. Joe

had even left an empty spot open on the wall,

“for when Sinatra comes in.”

Nicola

loved

the streets around Arthur Avenue, how

they rang with the sounds of store owners

singing "Oh Mari!

Quanta

suonno ca perdo per te”—“Oh, Marie, I

have lost so much sleep over you."

The air smelled of garlic and tomato, fresh

basil, and freshly ground coffee. Yankee

pennants festooned the storefronts, and old

men sat on folding chairs at their caffés to

watch the soccer games from Italy, sip

bittersweet liqueurs, and read the sports

pages of Il

Progresso.

Outside Randazzo’s Fish Market, people

gobbled up fresh clams and oysters from the

ice counter; baby lambs hung in the window at

Biancardi’s Meats; in summer the pastry shops

brought out freezers with Italian ices—lemon,

chocolate, strawberry—scooped and patted into

little pleated paper cups; at the Calandra

Cheese store they sold fresh mozzarella and

ricotta, along with aged provolone and

parmigiano; across 187th Street at the Mt.

Carmel Candy Store they still made New York

egg creams—a masterfully rendered concoction

of U-Bet chocolate syrup, ice cold milk and

seltzer, no egg, no cream; at Borgatti’s

Noodles, three generations of the family cut

egg noodles into precise widths on a chugging

machine that rang the rafters off the

building; around the corner at Terranova

Bakery, men with fire-scarred arms pulled

steaming loaves from the city’s last

coal-fired oven, as much an historical

artifact as a symbol of the neighborhood’s

refusal to change. In fact, just that past

year, 1987, a movie called “Moonstruck”

starring Cher and Nicholas Cage used Terranova

for the bakery scenes.

Nicola

enjoyed greeting the customers at Bella

Napoli, most of whom she knew, both those who

lived in the neighborhood and those who had

moved out of it. They still came back to

shop on the avenue and to eat in the

restaurants, so the pizza oven at Bella Napoli

was roaring from morning till

midnight—although Joe Bastone would serve

pizza after six p.m. only

if the customer also ordered other food. For

in those days, full-fledged Italian

restaurants played down the fact that they

were once mere pizzerias—then considered the

most common of street foods—no matter how

popular the pies were everywhere in America.

Biancardi's

Meats

Ah, but what they did to

pizza outside of New York! At

the drop of a moppine, Joe would roar his

disgust for what pizza had become

elsewhere—hell!—even in most parts of New York. Pizzas

had grown too large, too thick, packed with

too many disparate ingredients of low quality,

the mozzarella packaged and bought by the ton,

the tomato sauce out of a goddamn can, and the

crust!

He could not even imagine how his competitors

got the crust so grossly wrong, turning it

into thick, bread-like rounds that ended up

tasting like a goddamn hero loaf, chewy and

nothing more.

And if you were on very good terms with

Joe, which meant you were a regular customer

who told him his pizzas were absolutely the

best, he might confide that some of the

Belmont pizzerias were turning out crap, then

say, “I’ll kill you if you tell them what I

said.” Then

he’d smile, wave his hands in the air and go

back to the kitchen to stretch more dough—but

never like those idiots who tossed the stuff

in the air just for show.

So, even though Joe Bastone

had made his reputation and his principal

profit from his fabulous pizza, he wanted

people to love Bella  Napoli for its other

food, which was not nearly as good as those

nonpareil pies.

Nicola never said a word about it,

often waving off Joe’s offer to taste a new

dish by saying she was on a diet, to which Joe

would always say, “On a diet. Always

with the diet!

Nicky, you’re already too skinny for an

Italian girl. You gotta put some meat on those

bones, bella. Men

love the curves!”

Napoli for its other

food, which was not nearly as good as those

nonpareil pies.

Nicola never said a word about it,

often waving off Joe’s offer to taste a new

dish by saying she was on a diet, to which Joe

would always say, “On a diet. Always

with the diet!

Nicky, you’re already too skinny for an

Italian girl. You gotta put some meat on those

bones, bella. Men

love the curves!”

Nicola just nodded and smiled, well

aware that she had none of the voluptuary

curves of her sisters or of so many other

Italian women in the neighborhood. She

most certainly had a beautiful body, slim

hips, an enviable bust line, but it was her

face and her olive skin, dark brown eyes and

lustrous black hair that made every man who

came through the door at Bella Napoli fall in

love with her, and she’d developed a whole

patter for warding off the more obnoxious guys

who put the moves on her, sometimes while

their wives or girlfriends were eating

linguine three tables away.

Terranova Bakery

Of

course, she could also count on the protection

of Joe and her brother Tony, who, with typical

Italian bravado, both swore that Nicky was too

good for any of them, a fraternalistic opinion

she had long ago tired of hearing, as if she

were so unusual, so distant, so virginal that

no man could ever truly appreciate her for her

cultured demeanor or those virtues that had

been bred into her by her family.

Not since high

school, when she really was

very skinny, had Nicola had a boyfriend, a kid

who broke her heart by moving with his family

to Glen Cove, Long Island, promising he’d call

her and meet her in the city, but he never did

after moving out of the neighborhood. Afterwards

she found most of the Bronx guys strutted

their Italian macho with a swagger derived

from watching the first four “Rocky” movies,

even if the character of Rocky Balboa lived in

Philadelphia.

Her grandmother had told Nicola more

than once that it was not a bad thing to be a

little bit of a snob.

BELOVED

ITALIAN-AMERICAN RESTAURATEUR

JOSEPH MIGLIUCCI PASSES AWAY

I

am very sorry to report that one of the great

men of Italian-American food has passed away,

owing to Covid-19. Joseph Migliucci, co-owner

with his family of Mario’s restaurant on

Arthur Avenue in the Bronx, was part of five

generations who kept the flame of

Italian-American cooking alive and well.

I

am very sorry to report that one of the great

men of Italian-American food has passed away,

owing to Covid-19. Joseph Migliucci, co-owner

with his family of Mario’s restaurant on

Arthur Avenue in the Bronx, was part of five

generations who kept the flame of

Italian-American cooking alive and well.

Mario’s opened a century

ago in the Belmont neighborhood of the Bronx

as a pizza window shop and expanded into a

full-service restaurant in the 1930s. Mario

Migliucci and his wife, Rose, with their

children, Joe and Diane, then grandchildren,

always ran the place like a true family

restaurant, and it was where countless family

parties were held week after week.

After Mario’s death in 1998, and Rose’s

ten years later, Joseph and his wife, Barbara,

and today his daughter Regina, kept the

restaurant going with the same degree of

energy, passion and familial cordiality.

You’d never leave Mario’s without a

member of the family coming over to make sure

you enjoyed your meal. Usually it was Joe, who

demonstrated the rare but enduring benevolence

that seems so often absent from today’s trendy

new Italian restaurants and pizzerias around

town, where people are rushed in, rushed out,

with a “who-gets-what?” attitude and a stiff

bill at the end.

There are still double

tablecloths, long banquettes, good lighting

and carts are still wheeled from the kitchen

brimming with pizzas, cold and hot antipasti,

steaming pastas, generous main courses and

old-fashioned desserts.

The walls are lined with photos of

everyone who dined there, from Paul Newman to

Muhammad Ali and every New York Yankee, who

came from the Stadium nearby.

Joe

was a big, sweet, gentle giant, beloved by

everyone who frequented his wonderful

restaurant. Mario’s pizzas were famous, the

old-fashioned decor was cherished, and he

rarely took a day off, not only because he

convinced himself that something or somebody

in the restaurant needed his attention, but

because he knew that was where he was

happiest. Mario's just celebrated its 100th

anniversary, and Joe was there for 81 of them.

I’ll miss him so much.

By John Mariani

DOMAINE BOUSQUET WINES OF ARGENTINA

The growth and acceptance of

Argentinean wines in the global market, despite

the country’s boom-or-bust economy, is largely the

result of investments made and vineyards planted

just in the past 20 years. Today Argentina is the

world’s fifth largest wine producer (after France,

Italy, Spain and the U.S.), with more than 900

wineries and 17,000 producers. Total exports in

2019 were 19 million cases totaling $700 million

in sales.

Innovators like Bodegas Salentein, BenMarco and Susanna

Balbo have helped Argentina’s wines compete with

those of France and Italy. One of the pioneers of modern

Argentinean winemaking is Domaine Bousquet, which

was founded by a

third generation vintner from Carcassone,

France, named Jean Bouquet, and is now the

country’s largest, exporting 95% of their total

production of 4 million liters to more than 50

countries, totaling 5.6 million cases and $230

million in sales.

Guillaume Bousquet, Anne

Bousquet, Labid Al Ameri, Eva Al Ameri

Bousquet was on vacation in

Argentina in 1990 when he found that the terroir of

the remote, high-altitude Gualtallary Valley of

Argentina’s Mendoza region would be the ideal

location for him to make natural organically grown

wines.

I spoke with Bousquet’s daughter

Anne, an economist by training who as CEO now runs

the company with her husband, Labid Al Ameri,

a successful trader with Fidelity in Boston and now

president of the winery. Al Ameri joined the company

in 2005, Anne in 2008. A year later they moved to

Tupungato full-time, assuming full ownership of

Domaine Bousquet in 2011 (though they now live in

Miami, Florida).

I asked Anne Bousquet what appealed to her

father about the Gualtallary Valley.

“It was the altitude,” she said,

“ranging up to 5,249 feet, which

are the highest extremes of Mendoza’s

viticultural limits. Fast-forward to the present and

wine cognoscenti now recognize it as the source of

some of Mendoza’s finest wines. Back then, it was

virgin territory: tracts of semi-desert, nothing

planted, no water above ground, no electricity and a

single dirt track by way of access. Locals dismissed

the area as too cold for growing grapes.

“My father, on the other hand,

reckoned he’d found the perfect blend between his

French homeland and the New World—sunny, with  high natural acidity and a potential

for relatively fruit-forward wines.”

high natural acidity and a potential

for relatively fruit-forward wines.”

The first harvest was in 2003.

Winemaker Rodrigo Serrano joined Bousquet in late

2017.

“Before 2000 Uco Valley

was not exploited, and most of the wineries were

located near Mendoza city at a lower elevation,”

said Anne. “Now a lot of the wineries own

vineyards in Uco Valley. Also Argentina’s wine

industry was not as strong in exports in the 1990s;

they only started to grow significantly during the

2000s.”

Today, in order to meet

production, Bousquet grows fifty percent of its

grapes on 600 acres of land and buys the rest from

local farmers.

From the beginning the family was

devoted to sustainability and maintaining the land

in the healthiest condition. Irrigation is done

through a drop-by-drop system harnessing the Andean

Mountains’ run-off, which creates a lower ph in the

grapes, leading to higher acidity and color in the

wine. The sandy soil drainage makes the grapes

“stress” to obtain water, and the desert climate can

swing as much as 59 degrees in temperature from

morning through night. No synthetic pesticides,

herbicides or fertilizers are used. Bousquet is now

making non-sulfite wines under the Virgen label—a

red blend of Malbec, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet

Franc in 2018, and a Merlot in 2019. For that series

the wines spend no time in oak.

I asked Anne how Bousquet

copes in a world with a serious glut of wine supply.

“We intend to continue to compete

through our advantage, which is that all our wines

are made with certified organic grapes, and now we

also produce non-sulfite added wines,” she

said. “We have now established ourselves as

the leading Argentine winery for organic wines at a

time when demand for organic produce and wines has

been trending upward for the past few years in North

America and Europe (our strongest markets) and we

expect this trend to continue over the next few

years.”

She is more optimistic about

sales in China than many competitors I’ve

interviewed are at the moment. “China is a good

market,” she said,“but Argentina in general competes

in the Chinese market with wines from Europe, Chile

and Australia.”

I asked how global warming has

affected Bousquet’s viticulture. “Global warming

generally affects the timing and length of the

harvest,” she said. “This year, for example, the end

of the summer was very hot, and we started harvest

earlier than other years, and we will also finish

harvesting earlier. Another effect of global

warming is  that there is a lot less

snowfall during the winter compared to 15 or 20

years ago, which means that there is much less water

available for irrigation for agriculture. This led

the Mendoza government to stop authorizing new wells

several years ago, which in turn limits the growth

in new vineyards.”

that there is a lot less

snowfall during the winter compared to 15 or 20

years ago, which means that there is much less water

available for irrigation for agriculture. This led

the Mendoza government to stop authorizing new wells

several years ago, which in turn limits the growth

in new vineyards.”

Bousquet makes a remarkable range of

ten different labels, which range from Virgen and Premium Varietals

to sparkling wines, special editions and Gaia, this last

sold only to restaurants. I tasted several of their

line and was impressed with their quality first,

then their price. The Virgen Malbec, Cabernet

Sauvignon and Red Blend cost $13 a bottle; the

excellent Reserve Chardonnay $18; the Sparkling Charmat Method

Pinot-Noir –Chardonnay $13; and the Gaia

restaurant wines $20. The Ameri Malbec Blend

at the top of their line is $36.

Domaine Bousquet, together

with the other big names in Argentinean wines, is

offering some of the best values for varietals that

might well cost double the price of those from other

countries. In an industry where margins are slimmer

than they used to be, Domaine Bousquet seems to have

a very wide niche carved out for itself.

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

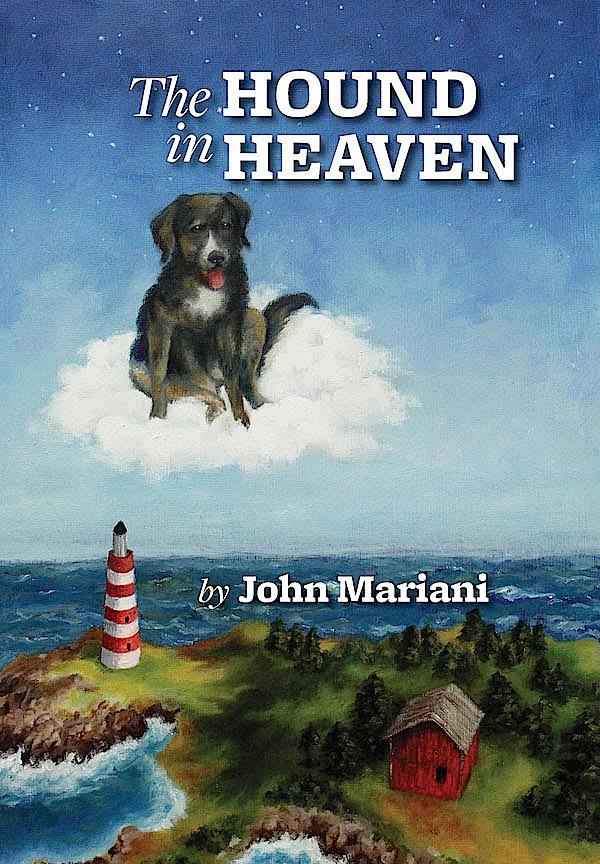

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las Vegas

JOHN CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas

food and restaurant scene since 1995. He is

the co-author of EATING LAS VEGAS – The 50

Essential Restaurants (as well as

the author of the Eating Las Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

Eating Las Vegas

JOHN CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas

food and restaurant scene since 1995. He is

the co-author of EATING LAS VEGAS – The 50

Essential Restaurants (as well as

the author of the Eating Las Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani,

Robert Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish,

and Brian Freedman. Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2020