MARIANI’S

Virtual Gourmet

June 21,

2020

NEWSLETTER

❖❖❖

IN THIS ISSUE

TAPAS AND DINNER

IN THE BASQUE COUNTRY

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

LOVE AND PIZZA

Chapter Thirteen

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

MILLBROOK WINERY

By Geoff Kalish

❖❖❖

TAPAS AND DINNER

IN THE BASQUE COUNTRY

By John Mariani

Berton in Bilbao

The

news that Spain’s restaurants are now open—with

reduced capacity and social distancing—makes the

prospect of visiting all the more savory at this

time, when deprivation makes the appetite roar.

It might well be said that the way people eat in

Spain is the way the rest of the world is now

eating. Not that Spanish foods like salt cod,

paella, and garlic soup are showing up on global

menus, but that the flavors of Spain’s

cuisine—sweet peppers, beans, ham, shellfish,

and the idea of tapas—have become part of the

repertoire of chefs from Portland to Paris.

Spanish wines are now considered among the

finest in the world, and the explosion of media

attention given to Spain’s “molecular cuisine” has

cooled down and never had much to do with the way

Spaniards actually love to eat, according to

revered regional traditions.

Nowhere

is this more distinctive than in the Basque

country of Northern Spain, especially in the

seaside city of San Sebastian (left) and the

surging cultural capital of Bilbao and La Rioja

Alta. The Basque country, stretching from the

French border westward to Cantabria and south to

Burgos, is only 4,500 square miles of territory,

and you can’t drive more than three hours in any

direction without crossing into another province.

It is richly indebted to foods from the Cantabrian

Sea: chipirones

(baby squid), ventresca

(tuna belly), rodaballo

(turbot), gambas

(shrimp), merluza (hake),

kokotxas

(hake cheeks),

bacalao

(cod), almejas, (clams), txangurro

(spider-crab), cigalas (langoustines),

and the famous—and very expensive--angulas

(baby eels), found in the estuaries of the Bay of

Biscay.

Nowhere

is this more distinctive than in the Basque

country of Northern Spain, especially in the

seaside city of San Sebastian (left) and the

surging cultural capital of Bilbao and La Rioja

Alta. The Basque country, stretching from the

French border westward to Cantabria and south to

Burgos, is only 4,500 square miles of territory,

and you can’t drive more than three hours in any

direction without crossing into another province.

It is richly indebted to foods from the Cantabrian

Sea: chipirones

(baby squid), ventresca

(tuna belly), rodaballo

(turbot), gambas

(shrimp), merluza (hake),

kokotxas

(hake cheeks),

bacalao

(cod), almejas, (clams), txangurro

(spider-crab), cigalas (langoustines),

and the famous—and very expensive--angulas

(baby eels), found in the estuaries of the Bay of

Biscay.

The farms around

Gernika provide wonderful pimientos and kidney

beans, mushrooms and potatoes. The sheep’s milk

Idiazabal cheese (once smoked in chimneys) has a

distinctive wild gaminess. Spanish hams are

nonpareil, and the lamb is as redolent of whatever

it feeds on.

People go to old cider houses to drink the

fresh, slightly alcoholic apple juice. And the

regional wines, including the fine red Rioja

Alavesa and the sparkling Txakoli, go perfectly

with hearty Basque cooking.

The easiest way to begin sampling all these

foods and wines is at the ubiquitous tapas bars,

called tascas. Most

nights in the casco viejo

(old quarter) of the gorgeous city of San

Sebastián, which arcs around the Bay of Biscay,

the bars are packed with locals who come to snack

on tapas—called pinchos—and

to drink red and rosé wines, cider, Mahou beer, or

Txakoli. The prowl from bar to bar is called el txikito,

referring to the squat, wide-mouthed glasses

drinks are served in.

The

array of tapas. listed on a blackboard, at

some bars may number thirty or more, though most

places serve perhaps twenty, some hot, some cold,

and are quite similar from bar to bar. You

always find thin, silky slices of Spanish ham on

crusty bread (good bread is a distinguishing

factor among tapas bars); scrambled eggs and

mushrooms; sardines and anchovies; stuffed

pimientos; fried croquetas;

and a potato omelet called tortilla de

patata. Everything is unstintingly fresh: in

a good

tasca those pinchos

made in the morning and not consumed by the

afternoon are discarded and new ones prepared for

the evening.

The best way to tell a good tapas bar from

a poor one among more than 500 in San Sebastián is

to measure the square footage you can manage to

occupy on the floor. Anything more than one square

foot means the bar is not very popular, and

jostling for a position near the bar itself is

part ritual and part endurance test.

The

array of tapas. listed on a blackboard, at

some bars may number thirty or more, though most

places serve perhaps twenty, some hot, some cold,

and are quite similar from bar to bar. You

always find thin, silky slices of Spanish ham on

crusty bread (good bread is a distinguishing

factor among tapas bars); scrambled eggs and

mushrooms; sardines and anchovies; stuffed

pimientos; fried croquetas;

and a potato omelet called tortilla de

patata. Everything is unstintingly fresh: in

a good

tasca those pinchos

made in the morning and not consumed by the

afternoon are discarded and new ones prepared for

the evening.

The best way to tell a good tapas bar from

a poor one among more than 500 in San Sebastián is

to measure the square footage you can manage to

occupy on the floor. Anything more than one square

foot means the bar is not very popular, and

jostling for a position near the bar itself is

part ritual and part endurance test.

The best tascas

offer a wider variety and several house

specialties.

One of the best is Gandarias

Jatetxea, which serves tripe, chorizo

sausage, several types of croquetas,

some with cod and a creamy béchamel inside, and

has exclusivity to carry Spain’s finest and most

expensive ham, from the producer Joselito.

My favorite tasca is

La Cuchara

de San Telmo (left). It is also the one with

the least wiggle room, so you will find yourself

cheek to jowl with locals‒although these days

there might be social distancing‒, who point to

the cold tapas on the bar or order the hot ones,

which on any given night might include shredded

oxtail, a risotto with blue Cabrales cheese, even

foie gras.

The tradition among barmen at the tascas is

to pour the wines by holding the bottle a good

foot away into the txikito glasses, and rarely do they

ever waste a drop. You get a short pour—maybe an

inch or two, the reason being that most people eat

one or two tapas, slug down their drink, and move

on. My own preference is to drink the cold, fizzy

Txakoli, whose alcohol is only about 10-11.5

percent. That way I don’t wobble (much) down the

street after my third tasca

visit.

From San Sebastian you can drive, as I

recently did, west on Route N634 along the

rippling seacoast, through  small

cities and tiny towns, many with ancient Basque

names that contain those identifying x’s and z’s

within their spelling. Less than an hour from San

Sebastián is the wonderful old, cobblestoned

fishing town of Getaria, cuddled around a snug

harbor dotted with seafood restaurants, where what

you will eat is what just came up from the docks

that morning.

small

cities and tiny towns, many with ancient Basque

names that contain those identifying x’s and z’s

within their spelling. Less than an hour from San

Sebastián is the wonderful old, cobblestoned

fishing town of Getaria, cuddled around a snug

harbor dotted with seafood restaurants, where what

you will eat is what just came up from the docks

that morning.

The prettiest

perch is at Kaia-Kaipe (right), a

restaurant above the harbor, with an extensive

menu that includes the velvety bacalao

dish called pil-pil,

made by combining olive oil and garlic with

cod until it becomes like mayonnaise. But my

favorite place is Iribar,

catty corner to Getaria’s San Salvador Church.

My wife and I sat on the

mezzanine, watching people drift in after one

o’clock for lunch.

The large menu is built around the day’s

fish, so we ordered a lustrous and tender octopus

salad, quickly grilled prawns glossy with olive

oil, and rodaballo

(turbot),

which, like all the fish, is grilled over an

outdoor charcoal grill, the fish moistened with

frequent sprinklings of olive oil, white wine, and

garlic. Lobster on the grill is remarkably well

priced (left).

My wife and I sat on the

mezzanine, watching people drift in after one

o’clock for lunch.

The large menu is built around the day’s

fish, so we ordered a lustrous and tender octopus

salad, quickly grilled prawns glossy with olive

oil, and rodaballo

(turbot),

which, like all the fish, is grilled over an

outdoor charcoal grill, the fish moistened with

frequent sprinklings of olive oil, white wine, and

garlic. Lobster on the grill is remarkably well

priced (left).

Farther west, we found Eneperi

Jatetxea (right)

off a hairpin turn along the swerving coast road

between Bakio and Bermeo. Timbered

throughout with a barn-like roof, plenty

of sailor memorabilia—even a small museum of

marine artifacts—and waitresses in traditional

blouses and long skirts, this is a rustic and

beautiful restaurant (with a somewhat lax service

staff) that is clearly for either a business meal

or serious night out. The menu still holds to

regional cookery but with considerable flair in

dishes like green Basque peppers stuffed with

onion and pork, the moist tail of hake in a red

pepper sauce, and an ice cream made from fresh

cheese and walnuts with Chinese gooseberries.

Eventually we

wound our way south through pine forests and tiny

towns like Eibar, Urkiola, and Durango to the

beautiful, broad city of Vitoria, called Gasteiz

in the Basque language. Bustling and modern, Vitoria

has been very careful to restore and maintain its

historic buildings, magnificent churches, and

green parks, and many streets are closed off to

motor traffic.

There we dined at one of the oldest

restaurants in northern Spain, El Portalón

(left),

hidden behind a nondescript door in

Eventually we

wound our way south through pine forests and tiny

towns like Eibar, Urkiola, and Durango to the

beautiful, broad city of Vitoria, called Gasteiz

in the Basque language. Bustling and modern, Vitoria

has been very careful to restore and maintain its

historic buildings, magnificent churches, and

green parks, and many streets are closed off to

motor traffic.

There we dined at one of the oldest

restaurants in northern Spain, El Portalón

(left),

hidden behind a nondescript door in a three-story building dating to

the 15th century, inside a warren of varnished

staircases, rough wooden beams, tiled floors, and

antique artwork. The food is hearty and generous,

from a thick, red bean soup riddled with cabbage

and slices of blood sausage, to squid cooked in

its own ink with rice, and a platter of flavorful,

fatty morsels of oxtail with sliced fried

potatoes.

a three-story building dating to

the 15th century, inside a warren of varnished

staircases, rough wooden beams, tiled floors, and

antique artwork. The food is hearty and generous,

from a thick, red bean soup riddled with cabbage

and slices of blood sausage, to squid cooked in

its own ink with rice, and a platter of flavorful,

fatty morsels of oxtail with sliced fried

potatoes.

So

much has been written about modern,

tourist-overrun Bilbao that its Basque character

has been somewhat displaced. But you will still

find it in the spirit of restaurants and tapas

bars all over the youthful, fashionable city,

particularly across the river in the Old Town

around the Cathedral of Santiago, now teeming with

new tascas

and cafés. Berton

is one of the best new ones, known for its ham. On the

other side of the river, where all the new

cultural facilities are built, Restaurante

Etxanobe (left)

is located on the third floor of the striking

Palaçio de Congresos y de la Musica, looking out

over the city from glass walls. Well-spaced tables

and impeccable service lend a sophisticated

ambiance to the evening, which begins with

excellent breads and six different olive oils,

followed by grilled langoustines scented with

vanilla, and a red rockfish with orange—inventive

but not molecular, simple cooking with real flair.

So

much has been written about modern,

tourist-overrun Bilbao that its Basque character

has been somewhat displaced. But you will still

find it in the spirit of restaurants and tapas

bars all over the youthful, fashionable city,

particularly across the river in the Old Town

around the Cathedral of Santiago, now teeming with

new tascas

and cafés. Berton

is one of the best new ones, known for its ham. On the

other side of the river, where all the new

cultural facilities are built, Restaurante

Etxanobe (left)

is located on the third floor of the striking

Palaçio de Congresos y de la Musica, looking out

over the city from glass walls. Well-spaced tables

and impeccable service lend a sophisticated

ambiance to the evening, which begins with

excellent breads and six different olive oils,

followed by grilled langoustines scented with

vanilla, and a red rockfish with orange—inventive

but not molecular, simple cooking with real flair.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Here are a few more tips about bar

hopping in San Sebastian:

• There are

at least a dozen tapas bars (and restaurants)

along the Calle 31 de Agosto, and every hotel will

provide a map of them.• Cold items line

the bar, while hot dishes are listed on

blackboards.

• The barman

totals up the bill merely by looking at the empty

plates you return. It’s an honor system.

• There is

no tipping required in a tasca.

• The locals

tend to eat late, but not nearly as late as they

do in Madrid. Start bar hopping after 8 p.m. and

the tascas will be swarming by 9. During the week

they start to close up around midnight, later on

weekends.

RESTAURANTS

Gandarias Jatetxea--Calle 31

Calle de Agosto 23, San Sebastián; www.restaurantegandarias.com

La Cuchara de San Telmo--Calle 31

de Agosto, 28, San Sebastián.

www.labicidesantelmo.com

Irib0ar, Kale Nagusia Kalea, 34

Getaria. www.iribargetaria.com

El Portalón—151 Correria,

Vitoria; www.restauranteelportalon.com

Kaia-Kaipe—General Arnao 4,

Getaria; www.kaia-kaipe.com

Eneperi Jatetxea—89 San Pelayo,

Bakio; www.eneperi.com.

Berton—11 Jardines, Bilbao;

https://www.berton.eus

Etxanobe—4 Avenue de

Abandoibarra, Bilbao; ladespensadeletxanobe.com

❖❖❖

By John Mariani

LOVE AND PIZZA

Since, for the time being, I am unable to write about or review New York City restaurants, I have decided instead to print a serialized version of my (unpublished) novel Love and Pizza, which takes place in New York and Italy and involves a young, beautiful Bronx woman named Nicola Santini from an Italian family impassioned about food. As the story goes on, Nicola, who is a student at Columbia University, struggles to maintain her roots while seeing a future that could lead her far from them—a future that involves a career and a love affair that would change her life forever. So, while New York’s restaurants remain closed, I will run a chapter of the Love and Pizza each week until the crisis is over. Afterwards I shall be offering the entire book digitally. I hope you like the idea and even more that you will love Nicola, her family and her friends. I’d love to know what you think. Contact me at loveandpizza123@gmail.com

—John Mariani

To read previous chapters go to archive (beginning with March 29, 2020, issue.

LOVE AND PIZZA

Cover Art By Galina Dargery

It

had been through an odd turn of fate and

fortune that Milan had become a major

fashion capital, when for decades it existed

in the shadow of far more elegant

cities like Rome and Florence. After World War

II, Florence, which had been a

major European textile center since the 14th

century, had come to dominate

Italian fashion through its production of

silks and leather goods made by

designers like the Ferragamo family, Gucci,

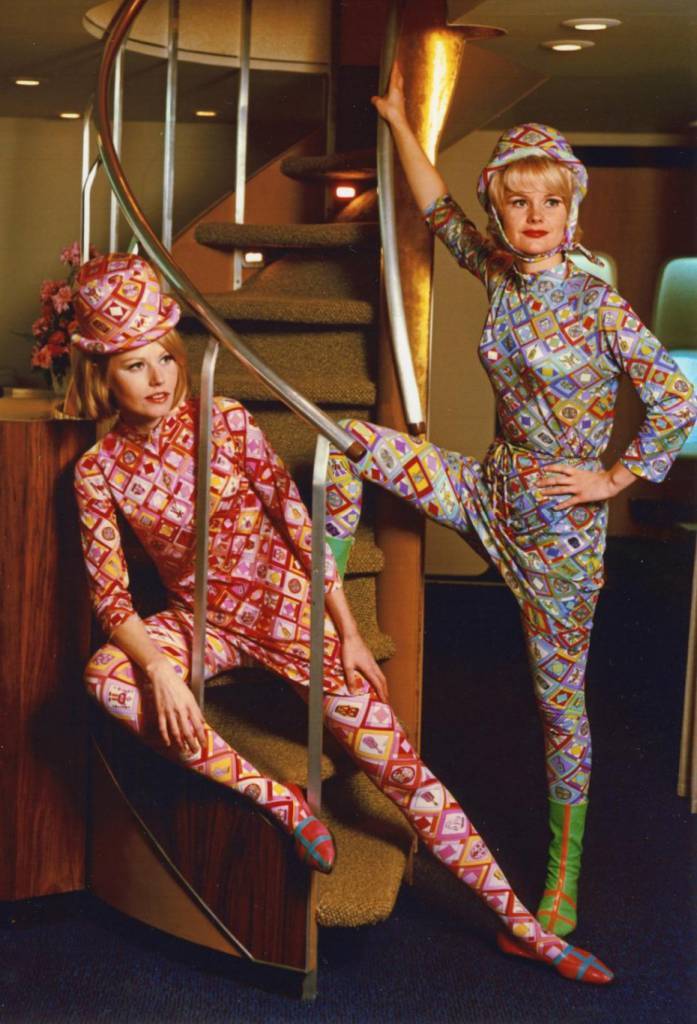

and the aristocratic Emilio Pucci (left)—all

Tuscans by birth and temperament.

There had

been modest versions of Fashion Week

held in Milan since 1958, and the city was home

to a few well-respected Milan

designers, including Krizia, Mila Schön, and

Biki. Elio Fiorucci, at first an

importer of British mod

sportswear at the time of “Swinging London,”

opened his own boutique in Milan

in 1967, emphasizing casual, youthful fashion.

That was the same year the

Missoni family, based in Trieste, was invited to

show their collection at

Florence’s Pitti Palace art museum.

There had

been modest versions of Fashion Week

held in Milan since 1958, and the city was home

to a few well-respected Milan

designers, including Krizia, Mila Schön, and

Biki. Elio Fiorucci, at first an

importer of British mod

sportswear at the time of “Swinging London,”

opened his own boutique in Milan

in 1967, emphasizing casual, youthful fashion.

That was the same year the

Missoni family, based in Trieste, was invited to

show their collection at

Florence’s Pitti Palace art museum.

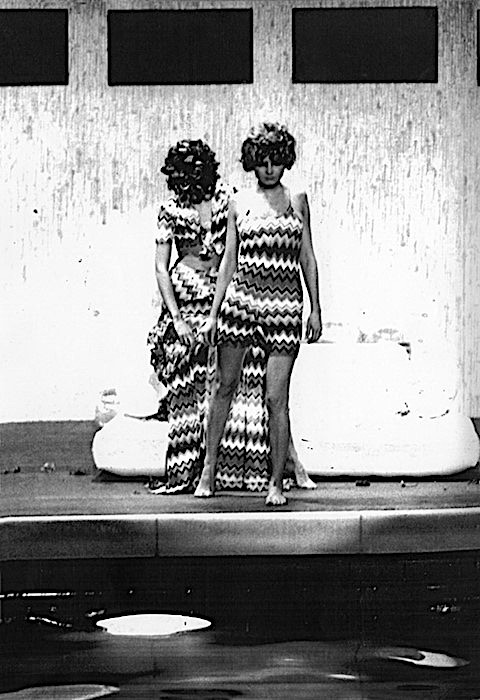

That show caused a sensation,

though as a succés

de scandale. Just before the show was to go on,

Rosita Missoni, the company’s

co-founder, noticed that the brassieres her

models were wearing were the wrong

color under her exquisitely thin knit dresses,

so she told them to discard

them (right). Owing

to the

near-transparency of the fabric and the lighting

in the palazzo, the women’s

sleek nudity showed through, to many viewers’

delight and to others’ sheer

horror. They

saw . . . nipples!

The Missonis were not asked back to the Pitti

the following year.

That began a slow exodus from

Florence to

Milan. The Missonis and many of  the Italian men’s wear designers

moved to the

city while Krizia relocated to a 16th century

palazzo in the city and shifted

her shows there. And they all began mounting

fashion shows with a distinctive

theatrical flair and Italian brio.

The press dubbed the shows “happenings,”

and, because there was no

official venue like the Pitti in Florence, the

Milan shows popped up all over

town, especially in the posh hotels like the

Principe di Savoia and the

Palace. Music

of the moment—including

the soundtrack from the movie “Star Wars” at one

show—boomed over crowds that

might include a thousand store buyers—a number

never known to attend shows in

Florence or Rome.

the Italian men’s wear designers

moved to the

city while Krizia relocated to a 16th century

palazzo in the city and shifted

her shows there. And they all began mounting

fashion shows with a distinctive

theatrical flair and Italian brio.

The press dubbed the shows “happenings,”

and, because there was no

official venue like the Pitti in Florence, the

Milan shows popped up all over

town, especially in the posh hotels like the

Principe di Savoia and the

Palace. Music

of the moment—including

the soundtrack from the movie “Star Wars” at one

show—boomed over crowds that

might include a thousand store buyers—a number

never known to attend shows in

Florence or Rome.

By the late 1970s, the

success of these shows,

based not so much on couture as on

ready-to-wear, quickly engaged interest from

Milan-based banks, whose lenders saw far more

potential in selling tens of

thousands of suits, dresses and sportswear

everywhere, rather than in selling

couture to a few hundred rich women around the

world.

In

1977 The

New York Times’ fashion

critic Carrie Donovan pronounced the city “a

fashion capital rivaling Paris and

New York.”

Investors sought out

young designers on the verge of breaking

through, and none was readier than

Giorgio Armani to make a transformative splash

in the international fashion

market.

In

1977 The

New York Times’ fashion

critic Carrie Donovan pronounced the city “a

fashion capital rivaling Paris and

New York.”

Investors sought out

young designers on the verge of breaking

through, and none was readier than

Giorgio Armani to make a transformative splash

in the international fashion

market.

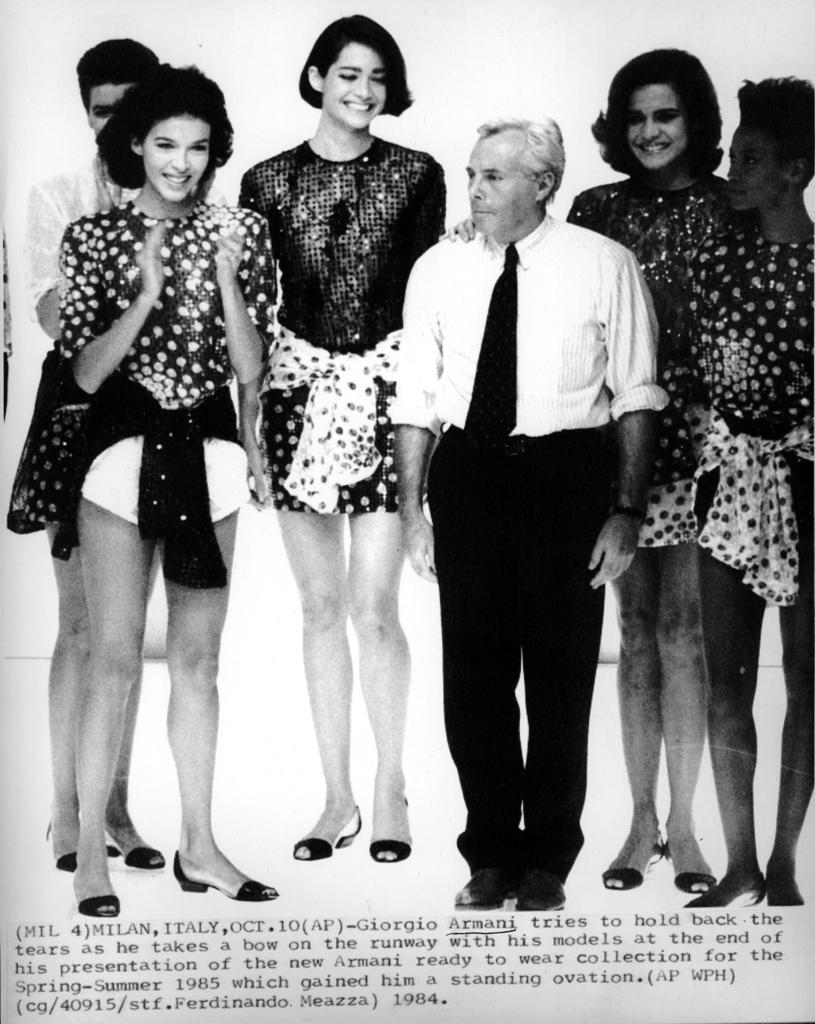

Armani (left)—the

name came via his father, who was

half Albanian—was born in Piacenza, a town in

Emilia-Romagna, and he had once

been a window-dresser at La Rinascente

department store in Milan, before

becoming an acolyte of Nino Cerruti.

Persuaded he could go out on his own, the

40-year-old Armani set up shop

in Milan on the Corso Venezia, at first

designing for other houses and winning

applause for shows with which he was involved at

the Pitti.

He

first

showed his own ready-to-wear and women’s lines

to overwhelming praise in

1975, and by the 1980s there were a perfume and

an underwear line, then the

Emporio Armani store in Milan. By

then everything was conceived and marketed from

his 19th century palazzo on the

centrally located Via Borgonuovo, where he lived

and worked—when he was not

relaxing at his villa outside of town, his

farmhouse in Forte dei Marmi, or his

hideaway on the remote island of Pantelleria.

Armani’s store, on Via San Andrea, was

antagonistically devoid of classic Milanese

trappings: the floors were rubber

matting, the walls translucent acrylic held up

by steel girders; track lights

brought everything in the store to life.

And prices were kept to a moderate

level—an Armani blazer sold for just

$330 at the store, half what it was in the

United States.

Having built up the most enviable

reputation and clientele of any

Italian designer—even appearing on the cover of

Time magazine—Armani didn’t even

hold runway shows for two years in

the early ‘80s, so there was a well-stoked fire

of intense interest as to what

his next show would be like.

For his menswear show, held earlier, in

January, Armani put up a huge

billboard to announce his lower priced Emporio

Armani men’s line. He bought magazine ads

showing an

androgynous-looking Charlotte Rampling dressed

in jackets in stripes and checks

that hinted at what was to come in the women’s

shows. By then, Armani’s annual

sales were soaring upwards to $100

million, and the new show was intended to be a

blockbuster among other Milan

extravaganzas.

And

Catherine and Nicola had passes for it!

Milan Fashion

Week,

which ran after the London and before the Paris

shows, began

in earnest on Monday, with

truckloads of clothes  shipped into the city

days before and every hotel room

booked weeks prior. Limousine

drivers made more money in that one week than

they did all season, many of them

hired on-call twenty-four hours a day, moving

their impatient passengers slowly

through or around what was called the Golden

Triangle—the cobbled streets

of Via della Spiga, Via Sant'Andrea and Via

Montenapoleone.

shipped into the city

days before and every hotel room

booked weeks prior. Limousine

drivers made more money in that one week than

they did all season, many of them

hired on-call twenty-four hours a day, moving

their impatient passengers slowly

through or around what was called the Golden

Triangle—the cobbled streets

of Via della Spiga, Via Sant'Andrea and Via

Montenapoleone.

Both the

choreographed

and the wholly unplanned madness of Fashion

Week, all avidly reported on by the

Italian press and dutifully covered by their

bemused European and American

colleagues, was, of course, much about the

pecking order: who would be seated

in the front rows, who would be the first to

interview the top and the new

designers; who would be invited to the most

coveted parties; and who would get

the “A” tables at the city’s most fashionable

restaurants, where the designers’

marketing people entertained buyers and buyers

entertained clients.

The

frenzy of merely getting into the shows was

astonishing to Nicola and

Catherine, largely because Italians had a long

tradition of never paying any

attention to orderly lines, preferring instead

just to assemble in a slowly

moving mass, in these cases a very well- dressed

mass, as were the two American

girls in their new outfits.

Catherine had been to fashion

shows in New

York, but these were much less structured, the

music completely different—more

American rock and roll than Italian disco, thank

God—and the atmosphere far

more entertaining than commercial.

Armani’s show was, as usual, held at his

office-and-residence in a

basement that had once served as a bomb shelter,

which he had reconfigured as a

theater. Nicola

and Catherine were

suitably dazzled by it all, astonished when they

were shown to seats just four

rows from the runway.

“I think I’m going to faint

from all this

perfume around us,” said Nicola, aromatically

assaulted on all sides by

conflicting scents that included plenty of the

new Armani, which had just been

introduced to coincide with his show.

“I know,” said Catherine,

blinking.

“You could go out of the house without

any perfume and just brush up against some of

these women and absorb theirs.”

The

girls then began taking note of the few

famous people they could identify, like the

fashion editor from Vogue,

Grace Mirabella, with her

short-cropped blonde hair, and Carrie Donovan of

the Times, famous for her

ridiculously large black-rimmed glasses that

made her look as if she were always taking an

eye test.

But most of the first-row people were

unknown to Nicola and Catherine, who said, “Most

of them are probably buyers

from, like, Bloomingdale’s, Bergdorf’s and

Saks.”

There were also a lot of very

well-dressed men

at the show, some in Armani. When

Nicola nodded in the direction of one or

another, Catherine just shook her head

and said, “Forget it, they’re all gay.”

“I doubt they’re all gay,” said Nicola.

“Well, if they aren’t, they

are either fat

buyers or rich guys just here to pick up the new

models.”

“Hm,” said Nicola, then,

noticing an extremely

handsome, impeccably dressed man with slightly

long hair standing off near the

door, asked, “What about him?”

“Oh God, he’s gorgeous!” said Catherine, her jaw

dropping. “I don't know, he

doesn’t look gay. Maybe he’s a bouncer.”

Nicola laughed, “That guy is

not a

bouncer. All the bouncers are

wearing the same outfit, over there, the muscle

heads in the black t-shirts and

jeans.”

But at that moment the

gorgeous man they’d been

discussing was saying goodbye to a woman with a

clipboard and earphones, He kissed

her on both cheeks and was out the door.

Nicola

sighed, “Well, guess we’ll never know.

Nicola

sighed, “Well, guess we’ll never know.

And

so it began, with a parade of models sashaying

down the catwalk in the

provocative, exaggerated way Catherine and

Nicola had mocked on their way over—which

had gotten them a couple of comments and wolf

whistles.

This was Armani’s tenth

women’s line, and the clothes had the flow and

caress of fabrics that seemed

only he could somehow obtain: the patterned

silks and the subtle woolen weaves,

the muted but true colors of taupe, gray, brown

and black.

Nicola, even from the fourth row, could

tell that what lay behind the flow and drape of

such fabrics seemingly so

unconstructed was in fact due to the kind of

exacting and exquisite tailoring

that had long distinguished Italian fashion and

showed the true artfulness of

the Armani style.

Like the

undercoatings and build-up of colors in

Renaissance paintings, Armani’s genius

was hidden beneath the exterior beauty of his

clothes. Sprezzatura,

after enormous hard work.

There

were many jackets—the article of clothing on

which Armani had

built his reputation—some short, some long, some

in black velvet, gathered at

the waist rather than hanging free; skirts were

above the knee and tight across

the hips or bouffant, flared by petticoats;

slacks fit like ski pants, with

foot straps; coats dropped to the ankle; tunics

were crafted from lace.

What

struck Nicola and Catherine most was that

the clothes were so clearly, so remarkably,

adapted to what a woman in 1986 could

actually wear, rather than the extreme gimmickry

of so much haute couture. Right

then and there most of the women

in the audience wanted to rip the clothes from

the models’ bodies and

immediately put them on to wear outside, to go

to work in, socialize in, even

fall asleep in, knowing that the fabrics would

look as fresh and unwrinkled the

next day as the night before.

After

successive struts down the runway, the willowy,

never smiling models stopped

appearing. “Well, the show looks like it’s

over,” said Catherine. “Let’s get out of here

before everyone

gets up.”

At

that, on the two-tier stage, each model

emerged for the last time from individual

cubicles, followed by a

sheepish-looking, bleary-eyed Giorgio Armani in

his black t-shirt and jeans. He

was applauded and greeted with successive waves

of bravos as the models

discreetly patted their slender hands together,

almost in unison.

By Geoff Kalish

Sitting on

a scenic Hudson Valley hill overlooking vineyards

and 3 ponds (manmade to moderate the surrounding

temperature), Millbrook Winery was founded in 1981

by former New York State Commissioner of

Agriculture John Dyson (left) and his brother-in-law,

David Bova. It was the first Hudson Valley winery

to produce wines only from vitis

vinifera grapes—classic European varietals,

as opposed to hybrid grapes used at the time by

other facilities. (Of note, Dyson was also

instrumental in the 1976 passage of New York

State’s Farm Winery Law, allowing farmers to make

and sell wine for only a small licensing fee,

thereby encouraging numerous small wineries

throughout the state.) And managed now primarily by

Mr. Bova and winemaker John Graziano, Millbrook

Winery produces approximately 15,000 cases of wine

annually.

Since it’s less than a

two-hour car ride from New York City and a popular

outing spot for tourists from the nearby counties

(especially Westchester), in the past the winery

was bustling on weekends, with tours and tastings,

and numerous special events as well as lunch

served on an outdoor terrace overlooking the

grounds. Also, in addition to sales of bottles at

the winery, wholesale sales to local restaurants

and retail shops in the area as well as in

Westchester County and New York City was brisk.

Obviously, with the COVID-19 pandemic, that’s

changed now and to gain some insight into the

future of Millbrook and other Hudson Valley

Wineries, I spoke to Bova. Some of his comments

follow:

Since it’s less than a

two-hour car ride from New York City and a popular

outing spot for tourists from the nearby counties

(especially Westchester), in the past the winery

was bustling on weekends, with tours and tastings,

and numerous special events as well as lunch

served on an outdoor terrace overlooking the

grounds. Also, in addition to sales of bottles at

the winery, wholesale sales to local restaurants

and retail shops in the area as well as in

Westchester County and New York City was brisk.

Obviously, with the COVID-19 pandemic, that’s

changed now and to gain some insight into the

future of Millbrook and other Hudson Valley

Wineries, I spoke to Bova. Some of his comments

follow:  “The key to our financial

success over the last many years has been selling

wine directly out the front door of the winery.

And last year we saw over 25,000 visitors to the

winery to taste wine, come to our Food Truck

Friday events or a Jazz concert on Saturday

evening. Of course, that is before COVID hit.

However, if Millbrook’s local support during this

COVID crisis is any indication, I believe there is

a great future for Hudson Valley wineries. While

our Tasting Room is open for pick-up only, without

tours or tastings taking place, out

Direct-to-Consumer sales are up over 200%. These

are from customers who want our wine and call in

to get it directly. In fact, we are thrilled that

our core customers are still supporting us even if

they can’t come here and taste with us. Actually,

I believe Millbrook’s long tenure (celebrating our

35th vintage this year) is very helpful. Of

course, and more importantly, the wines produced

by John Graziano (our only winemaker) have gotten

better over the years, so we have a solid track

record and reputation for producing high quality

wines.”

“The key to our financial

success over the last many years has been selling

wine directly out the front door of the winery.

And last year we saw over 25,000 visitors to the

winery to taste wine, come to our Food Truck

Friday events or a Jazz concert on Saturday

evening. Of course, that is before COVID hit.

However, if Millbrook’s local support during this

COVID crisis is any indication, I believe there is

a great future for Hudson Valley wineries. While

our Tasting Room is open for pick-up only, without

tours or tastings taking place, out

Direct-to-Consumer sales are up over 200%. These

are from customers who want our wine and call in

to get it directly. In fact, we are thrilled that

our core customers are still supporting us even if

they can’t come here and taste with us. Actually,

I believe Millbrook’s long tenure (celebrating our

35th vintage this year) is very helpful. Of

course, and more importantly, the wines produced

by John Graziano (our only winemaker) have gotten

better over the years, so we have a solid track

record and reputation for producing high quality

wines.”

To

follow-up on Bova’s comments I recently took a

ride to the winery for curb-side pick-up and

purchased bottles representative of the current

releases and the following comments are based on

tasting these as well as an “oldie” from my

cellar. (All prices provided are suggested retail

cost for 750ml bottles. Of note, there’s a 15%

discount for bottles purchased at the winery)

2018

Millbrook Chardonnay ($18.50). Made

from grapes grown in a variety of New York State

locales, following fermentation 50% of this wine

was aged in oak for 7 months. It shows a bouquet

and taste of ripe apples and lemon and a crisp

finish with notes of vanilla and anise. Mate it

with roasted chicken or turkey as well as grilled

branzino or orata.

2018

Millbrook Chardonnay ($18.50). Made

from grapes grown in a variety of New York State

locales, following fermentation 50% of this wine

was aged in oak for 7 months. It shows a bouquet

and taste of ripe apples and lemon and a crisp

finish with notes of vanilla and anise. Mate it

with roasted chicken or turkey as well as grilled

branzino or orata.

2019 Millbrook

Unoaked Chardonnay ($18.50). Produced

in the style of a French Chablis, this wine has a

bouquet and taste of apples and citrus with a

refreshing lemony finish. It marries well with

scallops, grilled trout or shrimp.

2018 Millbrook

Proprietor’s Special Reserve ($25). Similar

in style to a top-flight Napa Chardonnay, this

elegant barrel-fermented wine, from estate grown

Hudson Valley grapes, is loaded with flavors of

ripe apples, citrus and vanilla with a long smooth

finish. It makes ideal accompaniment to  halibut, grilled tuna,

even swordfish.

halibut, grilled tuna,

even swordfish.

2018 Millbrook

Proprietor’s Special Reserve Tocai Fruilano

($18). Made

from Hudson Valley estate grown grapes, this

varietal is usually associated with wines from

northeastern Italy. However, one would be hard

pressed to find it dissimilar from its Italian

cousin, showing a bouquet and flavors of ripe

pears, gooseberries and lime, with a touch of

almonds in its soft finish. Try it with mahi mahi,

cobia, turkey or even grilled pork chops.

2018 Millbrook Pinot

Noir ($23). This

barrel-aged, 100% Pinot Noir, with grapes hailing

from across New York State, has a bouquet and

taste of ripe plums, cranberry and notes of cherry

in its finish. It matches well with grilled

salmon, Artic char or roasted turkey, as well as

pasta with red sauce.

2018 Millbrook

Cabernet Franc ($23). Produced

from a blend of 79% Cabernet Franc, 9% Malbec and

2% Merlot grapes from the Millbrook estate as well

as other prime growing areas in New York State,

this wine was barrel-aged for 11 months prior to

bottling. It shows a bouquet and taste of ripe

raspberries and cassis with a long, smooth finish

with a touch of tannin. Mate it with grilled

steak, lamb or pork roasts as well as hamburgers

and pizza.

1986 Millbrook Claret

($14 when originally purchased in 1988)—Made

from a blend of Merlot (65%), Cabernet Sauvignon

(25%) and 10% other varietals, this wine has a

bouquet and flavor akin to an elegant, aged right

bank Bordeaux, with a scent of violets and a taste

of black truffles and chocolate with still a bit

of tannin in its finish. We enjoyed it with

grilled skirt steak and baked acorn squash.

Sponsored by

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las Vegas

JOHN CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas

food and restaurant scene since 1995. He is

the co-author of EATING LAS VEGAS – The 50

Essential Restaurants (as well as

the author of the Eating Las Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

Eating Las Vegas

JOHN CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas

food and restaurant scene since 1995. He is

the co-author of EATING LAS VEGAS – The 50

Essential Restaurants (as well as

the author of the Eating Las Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani,

Robert Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish,

and Brian Freedman. Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2020