MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

April

4, 2021

NEWSLETTER

IN THIS ISSUE

LE BERNARDIN RE-OPENS AND SHOWS

HOW GRAND FINE DINING CAN BE

By John Mariani

CAPONE'S GOLD

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

Wine & Food Matches: What I’ve Learned This Past Year

by

Geoff Kalish

❖❖❖

LE BERNARDIN RE-OPENS AND SHOWS

HOW GRAND FINE DINING CAN BE

By John Mariani

The re-opening of New York’s Le

Bernardin is not just good

news for regulars who missed chef-partner Eric

Ripert’s exquisite French

seafood but for anyone who worried that fine

dining at the highest level could

not survive the pandemic. Indeed, like the

crocuses now sprouting, Le

Bernardin’s return gives one a real feeling

that things are returning to normal

and that the world will warm again.

On

a recent visit my wife and I found

that all is as it was within the elegantly

appointed dining room, except for

the absence of a few tables so as to meet New

York’s 50% occupancy rule and

social distancing. The sparkling bar lounge is

not yet open, but wine director

Aldo Sohm will greet you with a smile beneath a

mask, and you will be brought

to your table with the same grace as always by a

well-trained, impeccably

dressed staff. (Would that one could say the

same of Le Bernardin’s male

clientele, who have given up any semblance of

dressing appropriately in the way

the female guests still do. Alas, there are no

more rules for dress left.)

On

a recent visit my wife and I found

that all is as it was within the elegantly

appointed dining room, except for

the absence of a few tables so as to meet New

York’s 50% occupancy rule and

social distancing. The sparkling bar lounge is

not yet open, but wine director

Aldo Sohm will greet you with a smile beneath a

mask, and you will be brought

to your table with the same grace as always by a

well-trained, impeccably

dressed staff. (Would that one could say the

same of Le Bernardin’s male

clientele, who have given up any semblance of

dressing appropriately in the way

the female guests still do. Alas, there are no

more rules for dress left.)

The tables are large, set with thick

linens and napery. The softened butter in a

small ramekin, the pretty show

plates, the heavy silverware and featherweight

stemware are all the same. The

civilized level of sound  makes

conversation a joy, and the lighting is kind to

everyone.

makes

conversation a joy, and the lighting is kind to

everyone.

Opened by Maguy Lecoze and

her late brother Gilbert in 1986, now

co-owned with Ripert, Le Bernardin features a

style of cuisine that has never

changed but is always evolving. Eric Gestel is

executive chef. A few dishes

abide on the menu from the restaurant’s

inception—including the classic seafood

carpaccio that Le Bernardin pioneered and

everyone since has copied.

My

wife and I actually had a

reservation for her birthday exactly one year

ago, then Covid came to town and

Le Bernardin closed. Given the expense of

running such a place, there were

rumors it would never re-open, but, says Ripert,

his landlord proved a

blessing, and, though tough, survival was

assured. We were ecstatic to find out

it was going to re-open and booked a table

immediately. From the day it

re-opened reservations were not easy to come by,

indicating that New Yorkers

are very ready to return to fine dining.

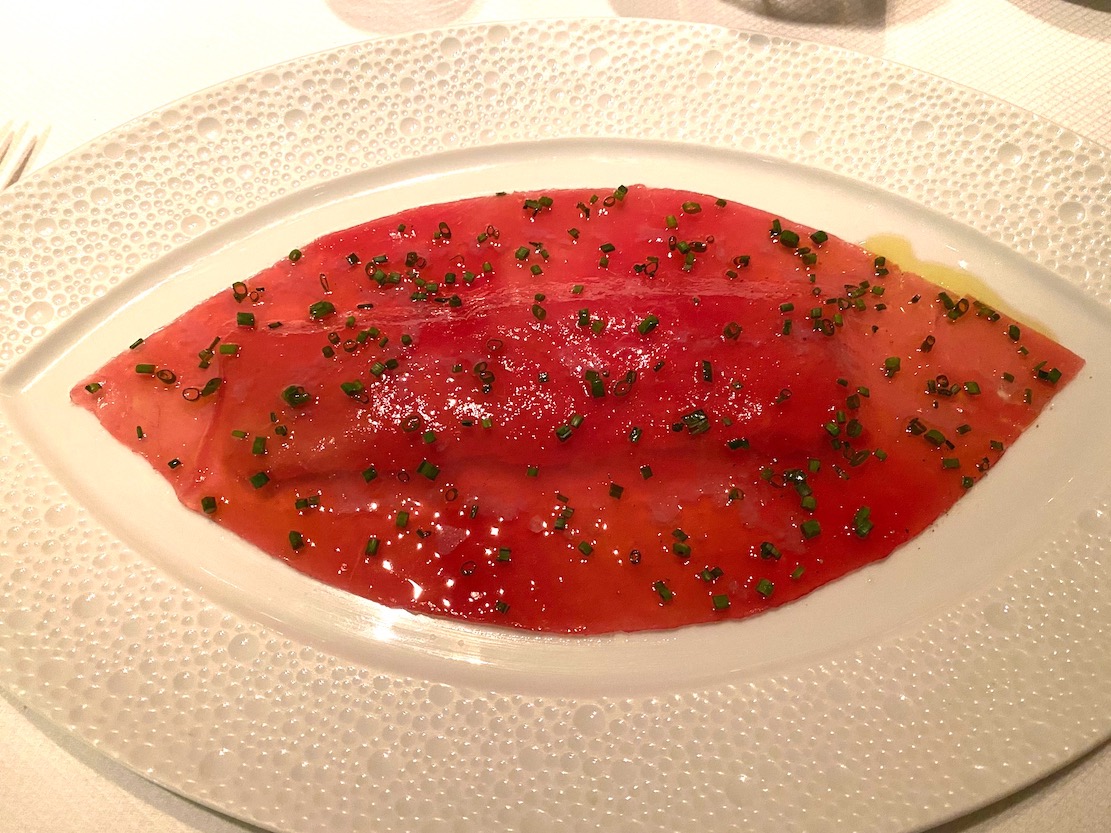

With an

apéritif of La Caravelle "Nina" non-vintage Champagne, we

sampled three

different breads baked on premises and enjoyed a

favorite dish—layers of thinly

pounded yellowfin tuna in the shape of lips atop

foie gras (above) and served with a

toasted baguette, chives and a gloss of olive

oil; it was as beautiful as it

was delicious. Striped bass was simply done with

a tartare topped with shavings

of black truffles and lush Périgord vinaigrette

(right).

With an

apéritif of La Caravelle "Nina" non-vintage Champagne, we

sampled three

different breads baked on premises and enjoyed a

favorite dish—layers of thinly

pounded yellowfin tuna in the shape of lips atop

foie gras (above) and served with a

toasted baguette, chives and a gloss of olive

oil; it was as beautiful as it

was delicious. Striped bass was simply done with

a tartare topped with shavings

of black truffles and lush Périgord vinaigrette

(right).

We then drank a creamy Meursault

Ballot-Millot 2018 with barely cooked sea

scallop in a brown butter-dashi

sauce

that showed the subtle influence of Asian

flavors that Le Bernardin has always

included. Plump Dover sole was sautéed with

toasted almonds and wild mushrooms

with a soy-lime emulsion. (Don’t for a moment

think that butter does not play a

significant part of French seafood

preparations.)

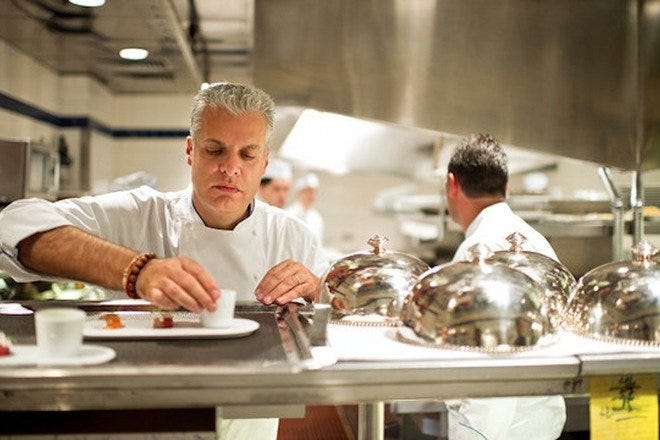

Photo:

Nigel Parry

Next came Faroe Islands salmon lightly

cooked and served with a black truffle

“pot-au-feu”

that proved salmon can be extremely delicate, in

contrast to all the inferior,

strongly fishy examples served elsewhere.

Le Bernardin does have a cheese tray

available, though we declined this time and went

straight to desserts: a mille-feuille

with a rhubarb-blackberry

compote, caramelized puff pastry so light you’d

think it could levitate and a

tangy yogurt sorbet. A very old-fashioned

Pavlova dessert was renewed with

exotic fruit, coconut sorbet and a

lemongrass-kefir lime sauce. The enhancement by

fruit acids and the temperate

use of sugar in Le Bernardin’s desserts is

crucial to their complexity of

flavor. What looked like a whole apple

revealed brown butter mousse with an apple

confit and a rich sabayon lashed

with Armagnac,

while an Easter egg

enclosed milk chocolate pot de

crème

with caramel foam, maple syrup and a “grain of

salt.” Of course, petit-fours and

chocolates were presented at meal’s end.

Photo:

Nigel Parry

We

had entered Le Bernardin at twilight on an early

spring

evening and left around ten, when New York is

usually still bustling and loud,

but instead the city had a bittersweet stillness

that made for a quiet trip

home during which we thought about the past

three hours when all seemed the way

we remembered it and the way it will be again.

Le Bernardin shows how that can

be done and does so with the same flourish and

refinement that has always been

its hallmark.

We

had entered Le Bernardin at twilight on an early

spring

evening and left around ten, when New York is

usually still bustling and loud,

but instead the city had a bittersweet stillness

that made for a quiet trip

home during which we thought about the past

three hours when all seemed the way

we remembered it and the way it will be again.

Le Bernardin shows how that can

be done and does so with the same flourish and

refinement that has always been

its hallmark.

Currently Le Bernardin is open only for

dinner, Monday through Saturday,

and guests must leave as of 11

o’clock.

(In the past people would still be coming in for

dinner at ten.) Still, opening

at 5 p.m.,

they can do two seatings per

night. They

have not yet opened for

lunch because there is no business midday.

Photo:

Nigel Parry

And for all its

elegance and

excellence,

you do not pay an outrageous

price, by comparison to similar restaurants

elsewhere. A four-course

dinner is $180—though this does not count the

little extras and petit-fours

that seem inevitable—and an eight-course tasting

menu $275 or

$425 with wine pairing.

Le

Bernardin is

located at 155 West 51st Street; 212-554-1515;

reservations also taken on line.

❖❖❖

CAPONE’S GOLD

By John Mariani

CHAPTER

ONE

.jpg) In a small

side chapel in the church of San

Giovanni Battista in the town of Angri, south of

Naples, Italy, the candles on

the altar are kept lighted all day and night in

remembrance of a departed soul

whose name has become inextricably linked to

this town in which he’d never set

foot: the most notorious gangster of the 20th

century, Alphonse Gabriel Capone.

In a small

side chapel in the church of San

Giovanni Battista in the town of Angri, south of

Naples, Italy, the candles on

the altar are kept lighted all day and night in

remembrance of a departed soul

whose name has become inextricably linked to

this town in which he’d never set

foot: the most notorious gangster of the 20th

century, Alphonse Gabriel Capone.

Ever since Capone’s death in 1947, at

the age of 48, someone had given instructions

and funding to the church in

order to maintain the votive candles as a way to

atone for his criminal life,

perhaps allowing him to avoid an eternity in

Hell by spending many years, even

centuries, in Purgatory.

Angri—not Chicago or Palm Island,

Florida, where Capone spent most of his career

as the most powerful crime boss

in America—seems to have been chosen for the

perpetual vigil because it was the

birthplace of his mother, a seamstress named

Teresina Raiola, and father,

Gabriele Capone, who emigrated to the New York

borough of Brooklyn in the

1880s. There,

in the Italian section of

Williamsburg, Alphonse Gabriel Capone was born,

one of nine children in the

family.

None of Capone’s family except Teresina

ever went back to visit the town of their

origins, and though a few people in

Angri regarded Al Capone as a kind of folk hero

who rose from poverty and

achieved great notoriety, his name was rarely

mentioned there, and tourists who

visited the town because of its distant link to

the mobster were usually

spurned when they asked what places of interest

might be associated with the

mobster, because none was.

Yet more than fifty years after his

death, the candles—made of the finest bees’

wax—still burned in the side chapel

that only a few family members knew was in

memory of Al Capone. Each

morning an altar boy would trim or

replace the candles in time for the seven

o’clock Mass, which was never

attended by more than a half dozen old women, or

perhaps by a young one praying

to God to allow her to become pregnant.

Each day and night the candles’ flames

flicker and glow in the dark, smoke-stained

chapel, year after year, decade

after decade, like the fires of Purgatory that

purified the souls of those who

dwelt there.

David

Greco knew seven ways the New

York Mafia used to kill a man besides shooting him

in the head, but he himself

had never used any of them while he was a rackets

cop, and none of them would

work on the giant hogweed that had invaded his

two-acre plot of land along the

Hudson River.

Giant hogweed

was more than just a nuisance—it

had been brought from Russia to the U.S. a

hundred years earlier as an ornamental plant—for

it had grown wild and rampant

throughout the Northeast, first in forests and

along roadsides, then invaded

backyards as a noxious weed, growing up to

fourteen feet tall and causing

anyone who came in contact with it to develop

blistering, scarring, even

blindness.

David Greco

knew that destroying it completely was a losing

battle, even after contacting

the State Department of Environmental

Conservation, which had for weeks

promised to send someone out to assess the

situation and make recommendations.

No matter how much he cut down or uprooted, the

grotesque weed would always

creep back, choking off the life of the carefully

landscaped indigenous plants

and foliage.

The

frustration dogged him daily, now that he was

forty-eight years old and retired

from the New York City police force, where as a

chief detective assigned to mob

activities, he had achieved a stellar record of

investigating, arresting and

putting Mafiosi away to the point where, by his

retirement, the mob had been

severely contained.

Detective

Greco prided himself on his slow, patient,

careful, highly detailed

investigations of the mob, first grabbing the

low-hanging fruit in order to get

the bosses at the top, by which point the only way

to beat the rap was for a

wise guy—the Mafia’s “made men”—to suborn a

witness or threaten a jurist. That

happened a lot when Greco started out,

but later on the low life members ratted out their

bosses, who, even if it took

two or three trials, ended up going to prison.

Of

course,

David Greco knew that the mob, like the giant

hogweed, could never be

eliminated because it was always mutating, so that

the demise of one group gave

rise to another.

By the mid-‘90s the Russians

and other Eastern European gangs had taken

territory and picked up the slack

from the Italians, and the newcomers were at least

as violent and vicious. In

the black and Latino neighborhoods the gangs were

younger, dealing street

drugs, and in constant battle with each other over

turf that might span less

than two or three city blocks. Even

there, the crack wars of the 1990s had burned out

and killed off a lot of the

suppliers and dealers.

Of

course,

David Greco knew that the mob, like the giant

hogweed, could never be

eliminated because it was always mutating, so that

the demise of one group gave

rise to another.

By the mid-‘90s the Russians

and other Eastern European gangs had taken

territory and picked up the slack

from the Italians, and the newcomers were at least

as violent and vicious. In

the black and Latino neighborhoods the gangs were

younger, dealing street

drugs, and in constant battle with each other over

turf that might span less

than two or three city blocks. Even

there, the crack wars of the 1990s had burned out

and killed off a lot of the

suppliers and dealers.

In any case,

he was happy to be out of and far away from it

all. In

the two years since he’d retired, David

Greco had barely kept in touch with his old

friends on the force and no longer

even picked up the New York Times, Post

or Daily

News. The

only items on his local paper’s police

blotter were arrests for D.U.I. or a rare house

break-in. Still,

David Greco locked his doors.

It was a warm

summer’s day while he was ripping out

hogweed that his speaker system buzzed from

the gate at the end of his

property. “What

now?” he sighed, for he

wasn’t expecting anyone and the delivery people

knew to leave packages at the

gate.

He put down

his shearing equipment, took off his thick garden

gloves, and said one word

into the speaker: “Yeah?”

“Detective

Greco?”

No one had

called him that in more than a year.

“Who’s

asking?” he replied.

“My name is

Katie Cavuto, and I’m the journalist who called

you the other day about a

possible job.”

David Greco

rolled his eyes and said, “You mean the one I told I was

retired and had no interest in?”

“Well, yes,”

stammered the woman, who recalled he had hung up

the phone about three seconds

later. “But I’m not looking for a security guard

or anything like that.”

There was no

response, no clicking off, so she continued. “I’m

a journalist and I’d like to

speak to you about possibly taking on an

interesting project with me.”

“What’s it

involve?”

“Well, I can’t

really explain it to you on the speaker.

May I come up for a few minutes?”

There was no

answer, but the buzzer unlatching the gate

sounded, so the woman entered,

walking up a gravel driveway towards the house,

where she saw the retired

detective walking down to meet her. She

stuck out her hand but David Greco raised his.

“Sorry, but if

we shake hands you might get some of the toxin

from the plant I’ve been trying

to root out.”

“Oh, what is

it, giant hogweed?”

“Matter of

fact it is. You

familiar with it?”

“A

little. My

parents have it growing in

their backyard, and it’s driving them crazy.”

“It’s very

nasty stuff.”

There was an

awkward pause, then David Greco asked, “So, what’s

this project you want to

talk to me about?”

“Well, as I

said, I’m a journalist, mostly for magazines, and

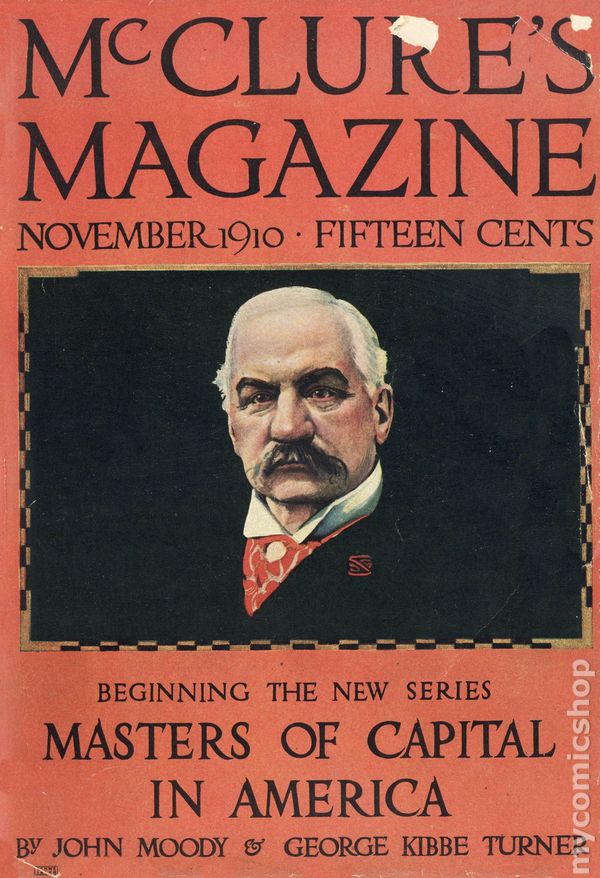

one of the ones I write for—McClure’s—has

asked me to write an

article about Al Capone’s lost fortune.”

“You mean his

theft of gold bullion no one’s been able to find

for fifty years?”

“Oh, so you

know about it?”

“A little.”

“Well, then

you also probably know that the Treasury

Department and the F.B.I. have had a

longstanding offer of $300,000 for any information

that leads to its

discovery.”

“And this

magazine—what’s it called? McClure’s?—thinks

that

you may succeed where everyone else has failed so

far over the last fifty

years?”

Katie Cavuto

smiled and said, “Actually, they don’t really

expect that I can find it, but

they think the story itself would be a good one. Nobody’s

written anything about it in

decades, but there has been some new archival

material on Al Capone and the mob

that might make for an exciting story.

As a matter of fact, I’ve done some

spadework and turned up some

interesting stuff.”

“Like what?”

“I wouldn’t be

much of a journalist if I told you, unless you

agreed to help me.”

David Greco

snickered and said, “Y’know, I think I liked you

people better when you called

yourselves reporters, rather than journalists.”

Katie Cavuto

countered, “Oh, I’m sure you never had a real high

regard for reporters either

in your line of work.”

“Usually they

get in the way of an investigation, always quoting

`high-placed sources’ when

they didn’t have any and printing complete

bullshit when they had nothing at

all. And,

obviously, they were all more

interested in the bad guys, how much money they

had, how much power they had,

how many guys they’d rubbed out, rather than write

about the work the police

had to do to arrest and convict them.”

“I can

imagine.”

“What I really

love about you . . . journalists,” he said

sarcastically, “is that unless a cop

is either working undercover to root out police

corruption or infiltrating the

mob, you ignore us, never mention the guys who do

all the dirty work, then you

just quote the police commissioner in your last

paragraph.”

Katie Cavuto

tried to keep calm, saying, “I feel your pain,

Detective Greco, but that’s as

much the fault of the police press office as it is

the writer of the story.

They control all the access.”

“Fair enough,”

said David Greco. “And frankly, after twenty years

on the force, the last thing

I want to see again is my name in the paper.

Such exposure ruins you for the job when

you believe your own

press. Makes

you crave it.”

“You certainly

had your share.”

“More than I

could justify or handle. But, anyhow, so you want

to interview me about

Capone—who died thirty years before I joined the

force? My

interest in the bum was only incidental to

knowing the history of the mobs in New York,

where, by the way, Capone never

really operated beyond a short stint as a lowlife

bouncer.”

“No,” said

Katie Cavuto, feeling the quick display of a

retired cop’s humility had run its

course, “I want you to help me throughout my

entire investigation of the story,

and the magazine is willing to pay you for your

time.”

“Let me get

this straight: you want me to traipse all over the

place with you on a wild

goose chase for Capone’s gold bullion? What’s the

fee?”

“Well, I

figure the story will take about six weeks to

complete—at least the research

part before I write it—and for that the magazine

is willing to pay you between

$10,000 and $15,000.”

David

Greco

tried to stifle his surprise, saying, “The money

sounds good, but what about

expenses?”

“They’re all

taken care of, too, wherever we have to go,

Chicago, Florida, wherever. We go

where the leads take us.”

“And, if in

the unlikely event we actually find where Capone’s

gold is hidden, who gets the

$300,000?”

“That’s the

really interesting part of the offer, at least for

you: If we find the gold,

the reward will be split two ways. The magazine

claims two-thirds of the money

and gives it to charity, and you get the other

third. I

can’t take it as a journalist, because it

wouldn’t be ethical.”

This time

David Greco could not stifle a low whistle. “So

you’re saying you don’t get a

penny from the reward and I get a hundred grand?”

“I’ll get paid

a very handsome fee for the article and my

reputation as a journalist would

soar. Who

knows, Pulitzer Prize? Maybe be

appointed head of a newspaper’s

investigative unit.”

“Or a job on ‘Entertainment Tonight’?

Sorry, that was a cheap shot.”

“Yeah, it

was,” said Katie Cavuto, knowing she had the

advantage for a moment.

“Sounds like

you don’t really need the money.”

“Anyone can

use $100,000, but it’s out of my hands.

I’m going into this with an eye on my

future.”

David Greco

went quiet for a moment, then said, “Miss Cavuto .

. .”

“Katie.”

“Okay, Katie.

I’m going to go inside and give my hands a good

scrubbing, then I’m coming back

out here to shake yours.”

© John Mariani, 2015

Wine & Food Matches:

What I’ve Learned This Past Year

By Geoff Kalish

Surprisingly, while many groups

and

publications rate wine on various scales (stars,

1-100, etc.), ratings for wine and food

matches by numbers, stars, etc. are

sparse. This

is quite curious as very few wines are

meant to be drunk without food; in fact in Italy and

some other countries many

people consider wine as food

(and for

a number of reasons it’s much healthier to consume

wine with food, but that’s a

discussion for another day) . But it’s been my

experience that most wine

ratings are formed by professionals

at tastings in which sips of wine after

wine are consumed, rarely with more than crackers or

water. And in my opinion

rating wines in a vacuum without food and then

proposing what foods they match

with seems more like hocus-pocus than anything close

to science.

are formed by professionals

at tastings in which sips of wine after

wine are consumed, rarely with more than crackers or

water. And in my opinion

rating wines in a vacuum without food and then

proposing what foods they match

with seems more like hocus-pocus than anything close

to science.

So, to see if traditional thinking about

what wine to drink with what fare is relevant or

folly, during the past year

I’ve experimented with my choices and kept written

notes on my findings. Of

course, this was made possible because since the

beginning of the Covid-19

pandemic we’ve eaten almost all our meals at home

and accompanied dinner with

wine most evenings, both newly purchased and from

the cellar. I’ve also

developed a simple scale for rating wine and food

combinations: E.A.T.

(Excellent, Average, Terrible).

Therefore, for those who think they know everything

about wine and food

matches, and for those just learning, the following

are some interesting

findings and insights.

● Well-aged

wines aren’t necessarily better

with food than young ones. In fact, many reds older

than 30 years from vintage

date (even well-stored bottles) seemed washed-out or

bitter and had the taste

of dried-out fruit with even simple fare. In

addition, very old Burgundies took

on a leathery taste, which some critics seem to

prize. However, how many foods

go well with the flavor of leather? And what tastes

good with dried-out fruit?

Maybe some cheeses, but we haven’t found them. So,

in general, I rate the taste

of very old wines (other than so called “dessert

wines,” like Port and late

harvest Rieslings) with almost all fare as a T (terrible). Moreover, we found that

almost all very old dry

whites (15 years or more from vintage date) tended

to show oxidation, and/or

unpleasant herbal tones and even “barnyard odors,”

no matter how well stored;

also rated T.

● Well-aged

wines aren’t necessarily better

with food than young ones. In fact, many reds older

than 30 years from vintage

date (even well-stored bottles) seemed washed-out or

bitter and had the taste

of dried-out fruit with even simple fare. In

addition, very old Burgundies took

on a leathery taste, which some critics seem to

prize. However, how many foods

go well with the flavor of leather? And what tastes

good with dried-out fruit?

Maybe some cheeses, but we haven’t found them. So,

in general, I rate the taste

of very old wines (other than so called “dessert

wines,” like Port and late

harvest Rieslings) with almost all fare as a T (terrible). Moreover, we found that

almost all very old dry

whites (15 years or more from vintage date) tended

to show oxidation, and/or

unpleasant herbal tones and even “barnyard odors,”

no matter how well stored;

also rated T.

● Of

course, there are exceptions to every

rule and of the many bottles of red over 30 years

old (including multiple

examples from France, Spain, Portugal, Italy and the

U.S.), we found that a

1985 Domaine Dominique Guyon Hautes Côtes de Nuits

“Cuvée des Dames de Vergy”

that still showed some hints of cherries and plums

and mated fairly well with

roasted chicken. And an older Bordeaux, like a 1986

Cos d’Estournel, mated

reasonably well (score A) with

grilled red snapper as well as with beef and lamb (A+). But as to great, memorable

matches, maybe there are some, but

we haven’t found them. So why drink very old wines

with a meal and decrease its

enjoyment?

● So why do

we continue to age wines for long

periods of time? Some feel it’s an intellectual

endeavor to study the

aesthetics of the beverage in the glass. I suppose

that’s OK, but if you are

eating along with drinking the wine—which one should

do to slow down the

alcohol absorption and its effect on the body—stick

to younger wines, say reds

less that 8-10 years old and whites under 5 years

from the vintage date.

●

Another finding was that while traditional wisdom

suggests that Cabernet

Sauvignon-based wines don’t mate

well with mild fish, we’ve found that many such

wines go well with

mild-flavored fish. For example, a 2014 Jordan

Cabernet Sauvignon went

swimmingly well with grilled branzino, earning an E. No wonder that this wine, not

generally garnering the highest

rating from critics, is one of the top selling

bottles in restaurants that

carry it. On

the other hand, as

expected, almost all white wines made awful matches

with beef and lamb (T), with

the only exception being

Gewürztraminer, with one from Warwick Valley in New

York State and another from

Ribeauville in Alsace mating well, but not

perfectly, with lamb burgers (A +) and

veal Marsala (A+).

● Also,

we found that rather young and fruity

Beaujolais (except most Beaujolais Nouveaux) went

well with almost

everything. For

example, a 2019 Coudert

Fleurie Cuvée Christie and a 2019 Château Thivin

from Côte de Brouilly, both

with a bouquet and taste of ripe plums, melons and

cassis, married harmoniously

with a range of fare running the gamut from turkey

to veal to pasta with red or

white sauce to swordfish and even shrimp scampi, all

garnering an E

rating.

● And

finally, we found that very sweet dessert

wines were at their worst with sweet desserts (T). In fact, they’re best with aged

cheeses. For example: a

California late-harvest Riesling tasted cloyingly

sweet with a

“black-and-white” cookie (T) as well as

a baked apple (T), but

made an E grade with a “Seriously Sharp

Cheddar” from Cabot Creamery in

Vermont, as well as a cave-aged cheddar from

Bobolink Dairy in Milford, N.J. On

the other hand, a Recioto della Valpolicella from

Serego Alighieri that had

good acidity as well as a moderate amount of

sweetness mated well (A) with

the cookie and baked apple (A), as

well as the cheese. It also

paired surprisingly well (A+) with

fare

that incorporated tomato-based sauces like pizza,

pasta and Turkish

eggplant. And,

of course, there’s the

question as to whether dessert wine is served before

or after dessert or is it

dessert itself. We found that it’s best served with

the “right” dessert, not as

a preamble or after-thought.

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

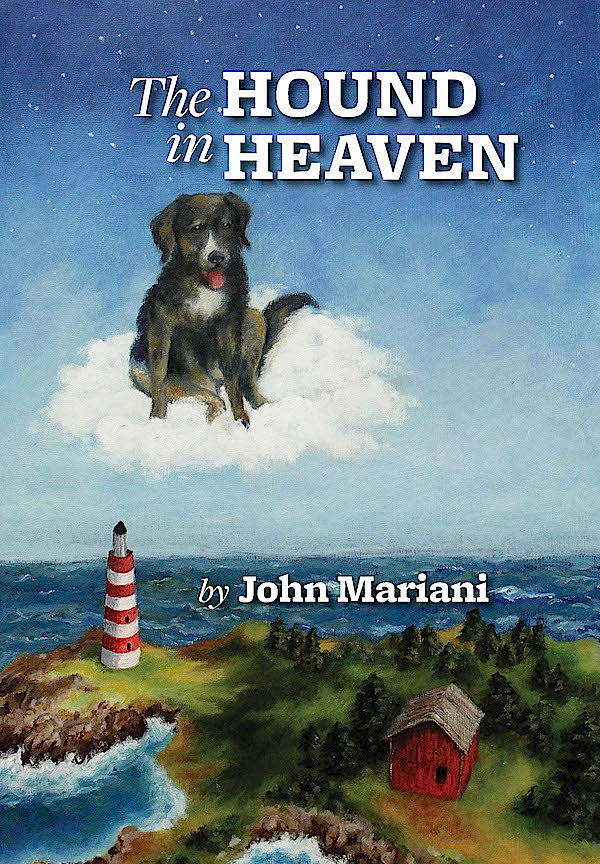

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las

Vegas JOHN CURTAS has been covering

the Las Vegas food and restaurant scene

since 1995. He is the co-author of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las

Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

Eating Las

Vegas JOHN CURTAS has been covering

the Las Vegas food and restaurant scene

since 1995. He is the co-author of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las

Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani,

Robert Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish,

and Brian Freedman. Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2021