MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

MAY 1, 2022

NEWSLETTER

ARCHIVE

"The First Prosciutto of Spring" by John Mariani

IN THIS ISSUE

DUBLIN 2022

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

EL QUIJOTE

By John Mariani

ANOTHER VERMEER

CHAPTER 17

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

Ricasoli Chianti Gran Selezione

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

will discuss the glamorous

oceanliners of the 1930s through 1950s. Go

to: WVOX.com.

The episode will also be archived at: almostgolden.

will discuss the glamorous

oceanliners of the 1930s through 1950s. Go

to: WVOX.com.

The episode will also be archived at: almostgolden.

❖❖❖

DUBLIN 2022

By John Mariani

One

may peruse in vain volumes of famous

quotations and find precious little in

praise of Ireland by its own most famous

authors, whose sad, tough love for

their native land was always being crashed on

the rocks of history. James

Joyce (below), the willing expatriate

who never returned to Ireland, spat, “Ireland

is

the old sow that eats her farrow,” while Yeats

in his day insisted Ireland’s

romantic past was already “dead and gone.”

George Bernard Shaw  was most

sanguine when he said, “Put an Irishman on the

spit and you can always get

another Irishman to turn him.” Oscar Wilde

somewhat less so: “We Irish are too

poetical to be poets; we are a nation of

brilliant failures, but we are the

greatest talkers since the Greeks.” Poet and

rebel Padraic Pearse sounded barely

hopeful

was most

sanguine when he said, “Put an Irishman on the

spit and you can always get

another Irishman to turn him.” Oscar Wilde

somewhat less so: “We Irish are too

poetical to be poets; we are a nation of

brilliant failures, but we are the

greatest talkers since the Greeks.” Poet and

rebel Padraic Pearse sounded barely

hopeful  after

the failure of the 1916 rebellion in Dublin

when he insisted,

“You cannot conquer Ireland. You cannot

extinguish the Irish passion for

freedom. If our deed has not been sufficient

to win freedom, then our children

will win by a better deed.”

after

the failure of the 1916 rebellion in Dublin

when he insisted,

“You cannot conquer Ireland. You cannot

extinguish the Irish passion for

freedom. If our deed has not been sufficient

to win freedom, then our children

will win by a better deed.”

Eventually, Ireland proved him right and

did win its independence, entering the modern

world on bandy legs until well

after World War II (it didn’t help that Ireland

declared neutrality and

extremist elements of the IRA worked with German

intelligence against the

British). Yet, despite being sentimentally

overly characterized as a shamrock

green land of leprechauns and fiddlers, modern

Ireland’s true spirit is most

manifest in the capital city of Dublin, which

today is one of the most splendid

and certainly most deeply cultural cities in

Europe. I suspect that if Joyce

and the rest were alive now, their sentiments

would be far more positive, even

swell with pride in what the last two

generations have achieved. (Indeed, all

those authors now have their monuments dotted

around Dublin, and Pearse even

has his own museum [right].)

The

city has never looked better,

especially since the disruptive gash of

construction to entrench the center’s

tram system is now gone. Most of the

city’s new construction is happening

north of the Liffey River, long the

poorest and derelict neighborhoods. The new

glass-and-steel bank and office

buildings show no more architectural distinction

than do any other European

cities’ and hardly fit in at all with Dublin’s

architectural traditions.

Yet,

the north, reached across the

happy Ha’Penny Bridge, has come to

life on its own, with a whimsical

statue of Joyce right there on the main drag of

O’Connell Street (left). There

are still commemorative bullet holes in

the walls left over from the Easter Rebellion of

April 1916 and the famous Post

Office defense site is well worth visiting. St.

Mary’s Church has been saved by

being transformed into a vast pub and restaurant

called The Church on Jervis

Street, where you may pat the bronze pate of

porter-maker Arthur Guinness,

whose presence is felt on every corner of the

city. Farther along there is now

the 390-foot stainless steel Spire of

Dublin, which no one sees the

significance of beyond replacing an 1809 pillar

topped with British Admiral

Horatio Nelson, whom the Irish loathed and who

the prescient Irish poet Louis

MacNeice said was “watching his world collapse.”

Yet,

the north, reached across the

happy Ha’Penny Bridge, has come to

life on its own, with a whimsical

statue of Joyce right there on the main drag of

O’Connell Street (left). There

are still commemorative bullet holes in

the walls left over from the Easter Rebellion of

April 1916 and the famous Post

Office defense site is well worth visiting. St.

Mary’s Church has been saved by

being transformed into a vast pub and restaurant

called The Church on Jervis

Street, where you may pat the bronze pate of

porter-maker Arthur Guinness,

whose presence is felt on every corner of the

city. Farther along there is now

the 390-foot stainless steel Spire of

Dublin, which no one sees the

significance of beyond replacing an 1809 pillar

topped with British Admiral

Horatio Nelson, whom the Irish loathed and who

the prescient Irish poet Louis

MacNeice said was “watching his world collapse.”

Dublin Castle in southwest Dublin dates

(after a devastating fire) to the 17th century,

with state apartments and St.

Patrick’s

Hall.

Patrick’s

Hall.

The best way to get around town is with

a Hop-on/Hop-off bus

ticket, discounted

if you book on-line.

The route runs for one hour 45 minutes and

26 stops,

with trained guides, stopping at all the

city's top attractions, including

Dublin Zoo, the Guinness Storehouse,

Trinity College and EPIC: The

Irish Emigration Museum (of which more in a

moment), along with sites

where Joyce, Wilde and Samuel Beckett (among

others) lived.

(Buses for the tour start at 9 a.m.

daily

from outside Dublin Bus Head Office at 59

Upper O'Connell Street; the last tour

of the day departs stop 1 at 5 p.m. during the

Autumn/Winter and 7 p.m. during

Summer.) Kids go free and there is free

entrance to the delightful Little

Museum of Dublin at St. Stephen’s Green,

whence you can also take a fine,

guided walking tour of this expansively

beautiful public space.

The

city’s other great green is Merrion

Square, twelve acres of it, with a statue of a

lounging Oscar Wilde (left) giving the

passersby what is either a wry smile or a

critical smirk. Ringing the Square are many of

Dublin’s finest townhouses,

hotels and restaurants. Incidentally, many of

the once brightly colored Dublin

doorways, made famous as a poster, have reverted

to the historic black color

they were before the 1960s ad promotion for the

city. (I’ll report on Dublin’s

hotels and restaurants in an upcoming column.)

The

city’s other great green is Merrion

Square, twelve acres of it, with a statue of a

lounging Oscar Wilde (left) giving the

passersby what is either a wry smile or a

critical smirk. Ringing the Square are many of

Dublin’s finest townhouses,

hotels and restaurants. Incidentally, many of

the once brightly colored Dublin

doorways, made famous as a poster, have reverted

to the historic black color

they were before the 1960s ad promotion for the

city. (I’ll report on Dublin’s

hotels and restaurants in an upcoming column.)

Hop on and off if you like, but Dublin

has a small center and you can stroll around it

in mere hours, unless you spend

your time at the better-than-ever National

Museum of archaeology and

Irish history and the National Gallery,

with its priceless The Taking

of Christ by Caravaggio.

Trinity

College (below) is so lovely and

green this time of year, and its great

Long Library is the magnificent home to the

uniquely beautiful medieval Book of

Kells, a new page of which is turned each day.

(Tickets are necessary.)

Trinity

College (below) is so lovely and

green this time of year, and its great

Long Library is the magnificent home to the

uniquely beautiful medieval Book of

Kells, a new page of which is turned each day.

(Tickets are necessary.)

A little away from downtown is St.

Patrick’s Cathedral, where Jonathan Swift was

Dean, and beyond that

the Guinness Storehouse, with its rich

history, superb exhibits and a

vast, panoramic view of the city from the

circular bar. There is also

an Irish Whiskey Museum worth a visit.

Downtown,

the main thoroughfare, closed

to cars, is Grafton Street (left),

made famous in many Irish lyrics and songs,

originally

a connecting lane dating to the 1700s and once a

high-end residential stretch.

Since then it’s become a fashionable shopping

street with as many international

as Irish brands and those persistent street

performers called buskers of

various talents, which once included Bono.

There’s a Molly Malone statue at one

end—she of the “alive-alive-o” fishmongers’

ditty—and what was once called the

Dandelion Market has become the wrought-iron

multi-level

St. Stephen’s Green Shopping Centre.

Downtown,

the main thoroughfare, closed

to cars, is Grafton Street (left),

made famous in many Irish lyrics and songs,

originally

a connecting lane dating to the 1700s and once a

high-end residential stretch.

Since then it’s become a fashionable shopping

street with as many international

as Irish brands and those persistent street

performers called buskers of

various talents, which once included Bono.

There’s a Molly Malone statue at one

end—she of the “alive-alive-o” fishmongers’

ditty—and what was once called the

Dandelion Market has become the wrought-iron

multi-level

St. Stephen’s Green Shopping Centre.

Perpendicular to Grafton Street are

several smaller streets with a better selection

of native Irish goods. (In

fact, I saw several “out of business” signs in

the windows of international

fashion boutiques on those streets.) Some of the

best include The Irish Store,

The Woolens Mills and CLOTH Dublin. For unique

Donegal tweeds and men’s and

women’s country clothing, I always make a visit

to Kevin & Howlin (right) on

Nassau

Street, across from Trinity, where each month

brings entirely new colors and

weavings of sturdy tweeds to last a lifetime,

even in Irish weather.

One of my favorite stops

off

Grafton is Sheridan’s Cheesemongers on Anne

Street, which has become so

successful that there are now branches in other

Irish cities. There you’ll find

small production Irish cheeses as nowhere else,

with delightful names like

Carrig Bru, Wicklow Bán and Drunken Saint.

And, if you’re going abroad, they’ll

shrink-wrap the cheeses so as to be

allowed through customs.

Over

the past twenty years the

neighborhood known as Temple Bar, near the

Houses of Parliament, has become a

crucible for the arts and entertainment, with

all the expected pubs and

restaurants (the Auld Dubliner is a

little quieter than some and has good

music) that service locals and visitors, who are

always heartily welcomed. It’s a

youthful area of Dublin, with the Ark Children's

Cultural Centre and Irish Film

Institute, along with the very fine

Irish Photography Centre, the Gaiety

School of Acting, IBAT College

Dublin, the New Theatre. The

Cow's Lane Market is known for its

fashion and design offerings on Saturdays.

Over

the past twenty years the

neighborhood known as Temple Bar, near the

Houses of Parliament, has become a

crucible for the arts and entertainment, with

all the expected pubs and

restaurants (the Auld Dubliner is a

little quieter than some and has good

music) that service locals and visitors, who are

always heartily welcomed. It’s a

youthful area of Dublin, with the Ark Children's

Cultural Centre and Irish Film

Institute, along with the very fine

Irish Photography Centre, the Gaiety

School of Acting, IBAT College

Dublin, the New Theatre. The

Cow's Lane Market is known for its

fashion and design offerings on Saturdays.

To put Dublin’s shadier past in

perspective, the city has declared it will turn

one of the last of what were

called the Magdalene Laundries, on McDermott

Street, into a museum showing the

true horrors of a Church-run workhouse for women

who strayed from the rules,

some prostitutes, some pregnant out of wedlock,

some nothing more than flirts

turned in by their parents into a life of years

of literal slavery in order to

save their souls. Only now in Ireland could the

thought emerge to preserve such

a hellish place as a way of coming to grips with

an unsavory past.

Far more inspiring, however, is the new

EPIC: The Irish Emigration Museum (below),

which, like the Titanic Museum in Belfast,

is a state-of-the-art living museum of history

focused on those who emigrated

during the agonies of the potato famine of the

1840s, in which millions starved

to death while millions more escaped to America

and Australia on small

transport boats, living below decks for weeks,

even months. One of those boats,

though a replica, is just outside the museum,

called the Jennie Johnston, whose captain was

among the most humane of his

profession, whose thousands of passengers—five

to a bunk—over several years all

survived journeys in which sickness, storms and

bare subsistence hung over

everyone. Others on lesser ships had a good

chance of never making it to their

destination alive.

Otherwise, within the museum

there are

thousands of hours of recording of immigrants,

letters, a family history

center, interactive touch screens, music and

dance, with impressive walls of

hundreds of famous Irish men and women, from

John F. Kennedy to Ronald Reagan

to Joe Biden, along with Irish-Americans

like

Gene Kelly, Kurt Cobain, Walt Disney and John

Ford, all presented as well

as anything at Washington’s Smithsonian.

❖❖❖

EL

QUIJOTE

Chelsea

Hotel

226 West 23rd Street

212-518-1843

By John Mariani

Photos by Eric Medsker

The rollicking history of the

Chelsea

Hotel, which opened as co-op apartments in

1885 before taking in guests as of

1905, has given this once-rundown building

a reputation for being archaically

trashy and really cool all at the same

time. Its heyday was back in the 1950s

and decades following as a cheap place to

stay put for a while if you were a

close-to-starving artist, but that cachet

brought in names like Thomas Wolfe,

Dylan Thomas, Arthur Miller and Tennessee

Williams and later a parade of hipsters

and rock stars like Janis Joplin (left)

and Bob Dylan. Andy Warhol shot his

unwatchable movie Chelsea Girls there.

Since

1930 the hotel has also been home

to El Quijote, one of a slew of Spanish

restaurants that once dotted the city

(most owned by Cubans) with names like El

Chico, Jai Alai, El

Flamenco, Fundador, Seville and

Havana-Madrid, all long gone. Certainly El

Quijote did not survive on the basis

of its food, which was, at best, a tepid

rendering of Spanish items, all with

tinted yellow rice on the side.

Since

1930 the hotel has also been home

to El Quijote, one of a slew of Spanish

restaurants that once dotted the city

(most owned by Cubans) with names like El

Chico, Jai Alai, El

Flamenco, Fundador, Seville and

Havana-Madrid, all long gone. Certainly El

Quijote did not survive on the basis

of its food, which was, at best, a tepid

rendering of Spanish items, all with

tinted yellow rice on the side.

Four years ago new owners came in,

closed

El Quixote, revamped it—meaning they cleaned

the place up and scraped off

decades of smoke and grime—without

compromising the funky charm of the long,

narrow dining room. Linoleum was ripped up

to expose a white tile floor, and a

folkloric

wall mural was uncovered on which a spindly

Don Quixote prepares to joust with

a windmill. The scruffy

ceilings will give you a feeling of what the

place used

to look like. Sadly, the tablecloths are

gone and the napkins are now cheap

paper.

Sunday Hospitality restaurant group

and

consultant Charles Seich have taken over and

brought in chef Byron Hogan (right),

who

has long experience cooking in Spain and is

demanding as to the products and

ingredients he buys, especially the seafood.

His is the kind of menu you’d now

find in the better restaurants of Madrid,

Bilbao and San Sebastián, definitely

not modernist but solidly traditional,

prepared with flair and a welcome higher

level of seasoning than you often find in

Spain, especially a judicious use of

chile peppers.

It’s a small restaurant and

reservations are tough to come by, unless

you want to dine early, then catch a

movie or one of several flamenco festivals

held in Chelsea, or late, which

seems more of a Chelsea Hotel kind of thing

to do. (A lobby bar, not part of El

Quijote, is due to open soon.) You’ll be

very cordially greeted, and, despite

the high ceilings, the noise level allows

for near-normal conversation, which

would be improved if they turned off the

unidentifiable throbbing music no one

could possibly want to hear.

The

service staff is knowledgeable—our

waiter was Spanish—and food and beverage

manager Zaneta Ramcharran makes

everything run smoothly. The all-too-red

jackets worn by waiters make them look

like interns on the floor of Wall Street.

The

service staff is knowledgeable—our

waiter was Spanish—and food and beverage

manager Zaneta Ramcharran makes

everything run smoothly. The all-too-red

jackets worn by waiters make them look

like interns on the floor of Wall Street.

The wine list, overseen by Claire

Paparazzo, is solid with modern Spanish

labels, and the sangria is really

delicious, flavored with cinnamon and given

a sweet-sour edge with balsamic

vinegar. Our table of four got two glasses

each from a pitcher ($48).

The menu is not categorized by first

and

main courses, though the listings at the top

include a number of  tapas

dishes,

from olives and guindilla

pickled

chile peppers ($9) to a very savory pan

con tomate of toasted country bread

smeared with garlic, olive oil and a

rich tomato confit ($12). There’s a plate of

three Spanish cheeses with quince

paste and almonds ($18), and the choice of

either Serrano ($19) or Ibérico

($60) ham. Not to be missed are the creamy,

piping hot bacalao (cod or ham)

croquettes ($13/$16) that I could make an

entire meal out

of.

Photo: John Mariani

tapas

dishes,

from olives and guindilla

pickled

chile peppers ($9) to a very savory pan

con tomate of toasted country bread

smeared with garlic, olive oil and a

rich tomato confit ($12). There’s a plate of

three Spanish cheeses with quince

paste and almonds ($18), and the choice of

either Serrano ($19) or Ibérico

($60) ham. Not to be missed are the creamy,

piping hot bacalao (cod or ham)

croquettes ($13/$16) that I could make an

entire meal out

of.

Photo: John Mariani

One of my favorite Basque dishes is

fish,

most often rodaballo

(turbot), whose

gelatin is whipped with garlic and olive oil

to make a rich mayonnaise. At El

Quijote, it is made with char-grilled merluza

(hake) with piquillo

peppers and

crispy but sweet, pulpy garlic ($25), and

it’s very good.

Gambas

al ajillo ($24) is another of the

beloved Spanish seafood dishes, here done

with blue, heads-on prawns on a la

plancha griddle with plenty of garlic,

arbequnia

olive oil and assertive seasonings that

infuse the shell and the body meat

completely. So, too, fideuá

de setas

($28) is a classic of toasted angel hair

spaghetti snapped into short pieces

and baked in a casserole with marinated

mushrooms and piquillo peppers that buoy the

smoky flavor of the pasta.

Gambas

al ajillo ($24) is another of the

beloved Spanish seafood dishes, here done

with blue, heads-on prawns on a la

plancha griddle with plenty of garlic,

arbequnia

olive oil and assertive seasonings that

infuse the shell and the body meat

completely. So, too, fideuá

de setas

($28) is a classic of toasted angel hair

spaghetti snapped into short pieces

and baked in a casserole with marinated

mushrooms and piquillo peppers that buoy the

smoky flavor of the pasta.

If paella

(below) is one of the defining tests

of a Spanish kitchen’s mettle— at least in

Valencia, where it’s prepared seaside over

an open fire—Hogan  has succeeded in

making

it in paella

pans for two people

(though our table of four, enjoying other

main courses, all shared the dish

hungrily), somewhat drier than I’ve had in

Valencia but, in addition to the

requisite shellfish (including more of those

marvelous gambas), is studded with

morsels of rabbit ($72). At the bottom is

the crispy rice called

socarrat that

everyone fights over.

has succeeded in

making

it in paella

pans for two people

(though our table of four, enjoying other

main courses, all shared the dish

hungrily), somewhat drier than I’ve had in

Valencia but, in addition to the

requisite shellfish (including more of those

marvelous gambas), is studded with

morsels of rabbit ($72). At the bottom is

the crispy rice called

socarrat that

everyone fights over.

For dessert I’d highly recommend the

rum-soaked gâteau Basque with tangy sweet

marmalade ($12). The soft-serve ice

cream with nuts ($8) had an odd smoky flavor

not to my taste.

So,

after a brief but much needed hiatus,

El Quijote, red neon sign outside and all,

has come back full force with the

same engaging and happy ambience it had when

it was more a hang-out than a

dining experience. Now,

it joins a

handful of New York’s first-rate Spanish

restaurants and a place to celebrate

and to soak up the spirit of New York

hipster history.

Open for dinner nightly.

❖❖❖

ANOTHER VERMEER

CHAPTER

SEVENTEEN

THE WHITE TERROR

Harry

Balaton

she already knew. She found out that the Russian

oil magnate Igor

Stepanossky, 54, had become very rich very soon

after the fall of the Soviet

Union, garnering multiple exclusive contracts

for oil companies and

transportation in Siberia. Stepanossky lived in

St. Petersburg and owned a

lavish apartment  in Monaco, rarely

leaving Europe, but quickly entered the art

market, first buying minor works of 19th century

French artists, then

first-rate Impressionist art, and had amassed a

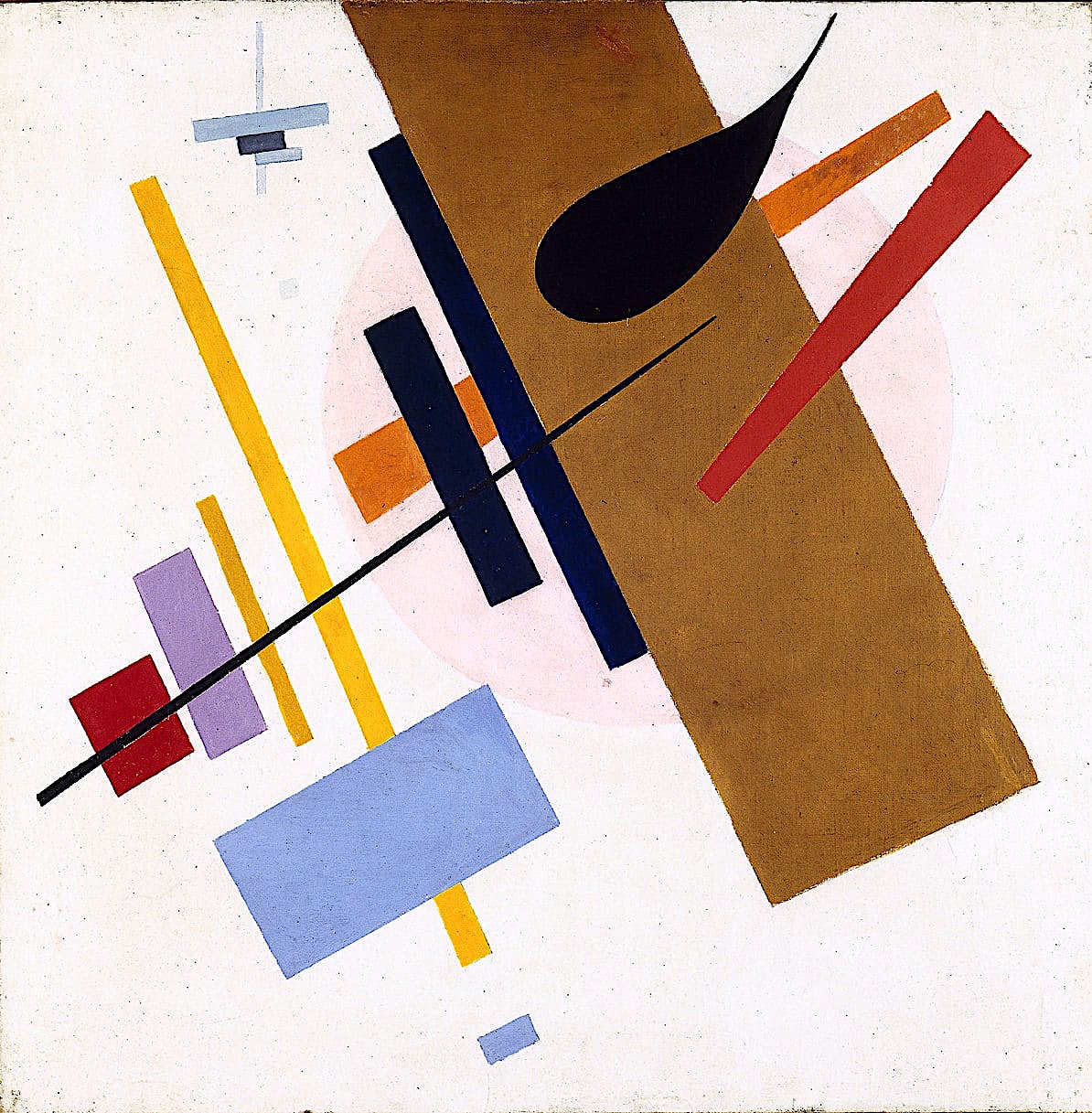

considerable collection of

works by the 20th century Russians—Kandinsky,

Chagall, and Malevich (right)—but he had

never bought any of 17th century Dutch masters.

in Monaco, rarely

leaving Europe, but quickly entered the art

market, first buying minor works of 19th century

French artists, then

first-rate Impressionist art, and had amassed a

considerable collection of

works by the 20th century Russians—Kandinsky,

Chagall, and Malevich (right)—but he had

never bought any of 17th century Dutch masters.

Nicholas

Danielides was from a well established Greek

shipping family that had acquired

its artwork after World War II, including ancient

Greek and Persian statuary,

and his collection of post-war European and

American art was of the first rank.

It had long been suspected that much of his

collection had been stolen by his

father, perhaps bought from the Nazis, but as long

as the works stayed in

Greece, authorities asked few questions.

At only 43 years of age, Danielides was

still a bachelor and considered

very much a playboy, with the requisite yachts and

homes all over the world,

with his base in Athens.

Jan

Dorenbosch, 65, was the son of a Dutch businessman

who was alleged to have had

business with Germany during the war but was never

convicted of any crime.

There were even accusations—largely

circumstantial—that his company’s

researchers worked with their Nazi colleagues on

the most horrific medical

experiments done on concentration camp victims.

Since

then his son had attempted to keep the Dorenbosch

name out of the newspapers

and was as secretive about his art holdings as he

was about his privately owned

pharmaceutical company. He lived in Amsterdam.

Since

then his son had attempted to keep the Dorenbosch

name out of the newspapers

and was as secretive about his art holdings as he

was about his privately owned

pharmaceutical company. He lived in Amsterdam.

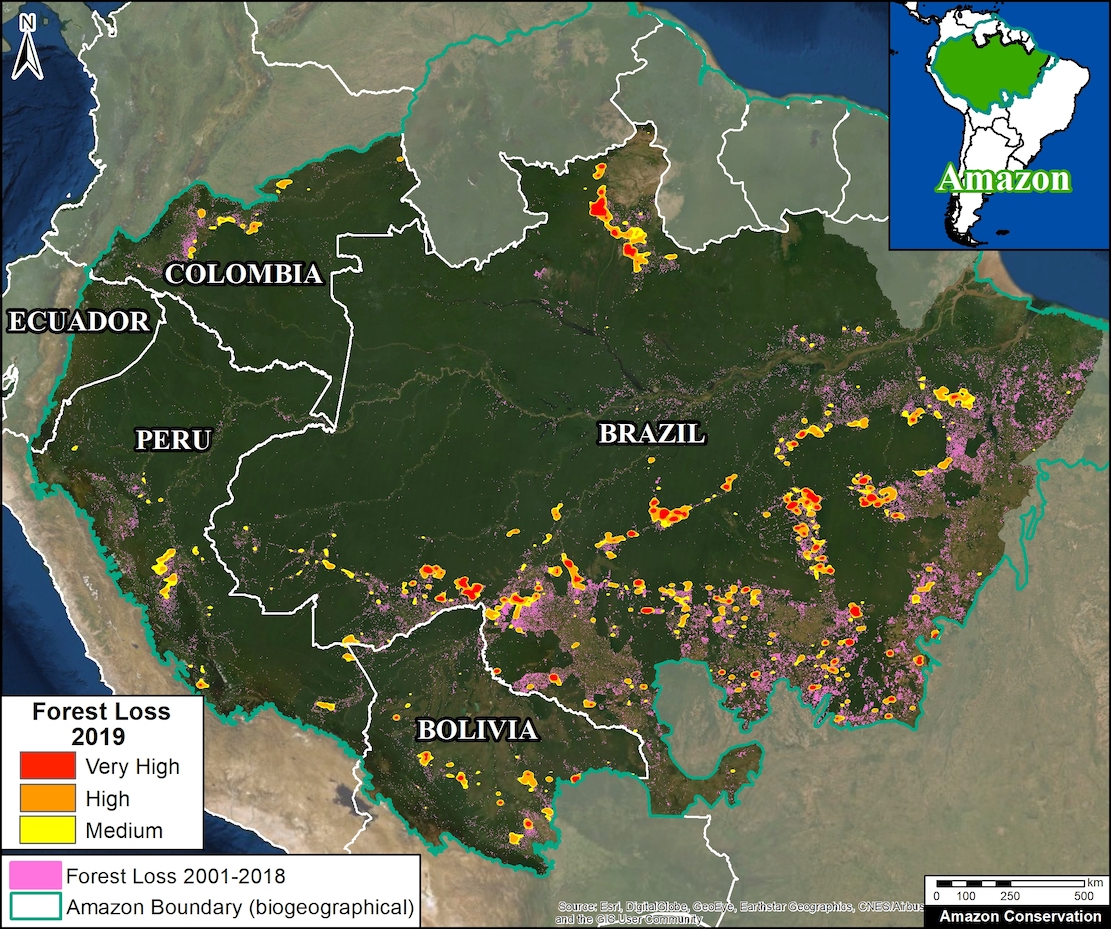

João

Correa’s fortune came largely from destruction of

Brazil’s rain forest, which

was losing the equivalent of 200 football fields

and more each day. Not only

did Correa, 40, provide the trucks,

tractors and cutting machinery for the

de-forestation but he also was South

America’s largest producer of lumber. He

protected himself from further scrutiny by buying

off politicians, philanthropy

and supporting the arts, often with donations to

museum from his own superb collection

of South American and African works.

Robert

Loudon, 62, had inherited his immense wealth from

his mother, who had founded

the Lavande cosmetics company, with branches and

laboratories in six countries,

including France, Russia and China. Largely he

devoted his time to philanthropy

and his art collection, which focused on Medieval

and Renaissance paintings and

sculpture. In the art world he was considered very

open about his collections,

whose works he often shared with museums.

Nothing had ever appeared about Louden to

suggest he had engaged in any

criminal activities beyond a youthful penchant for

orgies back in the 1970s at

his Gramercy Park townhouse and villa in St.

Barts.

Katie

saved Hai Shui for last, hoping the hypotheses

that came out of the Fordham

meeting would give her insight into the man.

But there was very little on Shui

in the Times

archives or business

magazines and only scattered references in the art

journals. He was considered

a very astute buyer with catholic tastes, though

his Chinese art holdings were

by far the largest in his collection. She did find

that he was worth upwards of

$7 billion, according to the Hurun Report,

which kept track of the wealth of Chinese tycoons,

placing him first among

Taiwanese billionaires.

insight into the man.

But there was very little on Shui

in the Times

archives or business

magazines and only scattered references in the art

journals. He was considered

a very astute buyer with catholic tastes, though

his Chinese art holdings were

by far the largest in his collection. She did find

that he was worth upwards of

$7 billion, according to the Hurun Report,

which kept track of the wealth of Chinese tycoons,

placing him first among

Taiwanese billionaires.

As

Prof. Lìu had said, many of the Shui families had

settled in Taiwan in the

early 17th century, during Vermeer’s lifetime.

From what Katie could gather, Hai Shui was

now the most eminent member

of his extended family, which began in the

petroleum business before World War

II, when Shui was a boy living in Beijing, at a

time when Japan held Taiwan as

a colony. After

the war, the Chinese

Communists took control of the mainland, and in

1949 the remnants of the

opposing Chinese Nationalists under Chiang

Kai-Shek evacuated to Taiwan, when

the Shui family moved back to the island.

For the time being, Britain had so far

maintained control of Hong

Kong.

Hai

Shui became president and chairman of the board of

the family business in 1980

and expanded its petroleum interests into

chemicals, becoming immensely wealthy

as Asia developed insatiable energy requirements,

needed to fuel their

developing economies.

Katie

put in a call to Prof. Lìu to ask if she knew

anything more about the Shui

family on Taiwan.

“Not

much, really,” she said. “They were among the two

million soldiers,

politicians, and business elite who emigrated to

Taiwan after the communists

took over the mainland. They all brought with them

a tremendous amount of

national treasures and grabbed up most of China’s

gold and foreign currency

reserves. Then civil war set in and Chiang

Kai-Sheik’s Nationalists declared

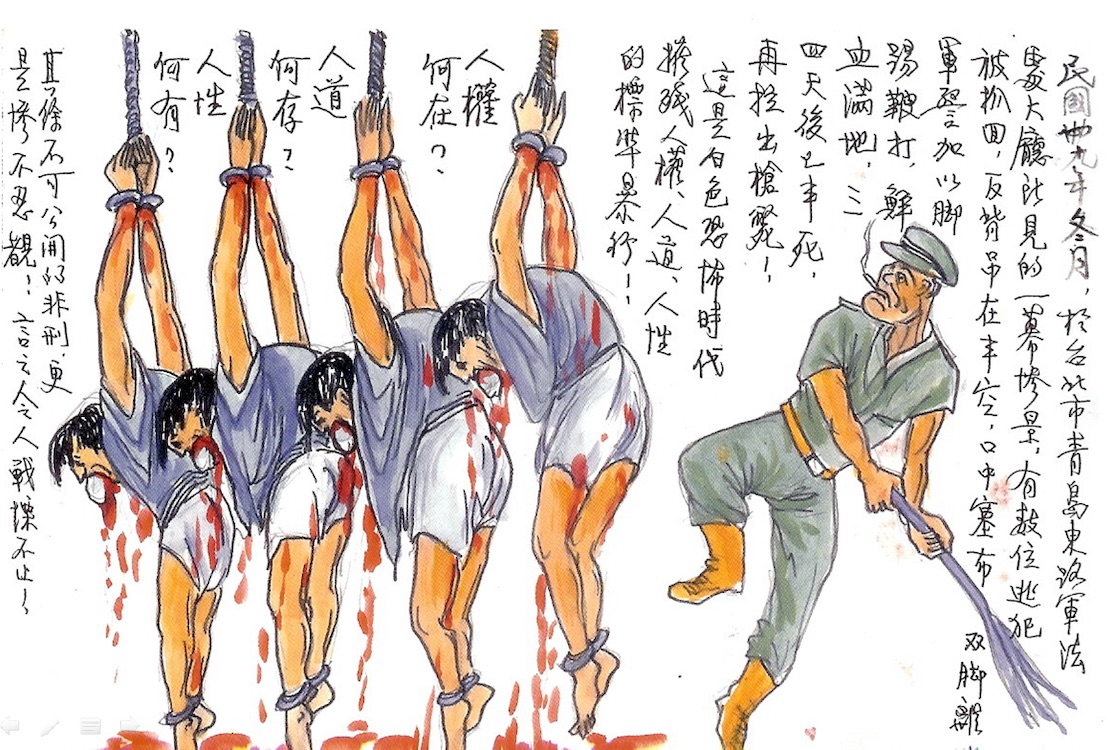

martial law on the island. It was called the

‘White Terror,’ and it’s estimated

up to 140,000 people suspected of communist

leanings were persecuted or killed.

Martial law was not repealed until 1987.”

“Not

much, really,” she said. “They were among the two

million soldiers,

politicians, and business elite who emigrated to

Taiwan after the communists

took over the mainland. They all brought with them

a tremendous amount of

national treasures and grabbed up most of China’s

gold and foreign currency

reserves. Then civil war set in and Chiang

Kai-Sheik’s Nationalists declared

martial law on the island. It was called the

‘White Terror,’ and it’s estimated

up to 140,000 people suspected of communist

leanings were persecuted or killed.

Martial law was not repealed until 1987.”

“So,

obviously, the Shuis were able to avoid the worst

of that?”

“They

must have been very well

connected to

Chiang Kai-Shek (below), yes. I daresay

they survived by cooperating with the

Nationalists in calling out their own business

competitors.”

“And

got richer because of it?”

“Yes,

they prospered and helped fuel Taiwan’s boom in

the 1970s, when, after Japan,

it became the second fastest growing economy in

Asia. Being in petro-chemicals,

the Shuis were very well positioned to become

immensely wealthy.”

As

agreed, Katie shared her research with John

Coleman, who in turn told Katie

that most of Hai Shui’s art collection was Chinese

sculpture, paintings, books,

porcelain, jade, with a smattering of European

art, mostly modern. Katie

dutifully told Coleman about the “sui jen”

connection proposed by Prof. Lìu, which the editor

found farfetched.

“I

get what you say about the alchemy in the

painting,” said Coleman, “but the

rest really seems an overly imaginative stretch.”

“It

doesn’t impress you that the globe on the table

just happens to be turned to

China and the Chinese words are painted right next

to it?” asked Katie. “From

what I know of Renaissance artists everything in a

painting had a symbolic meaning

or reference.”

“Yes,

that’s true, and maybe those words are phonetic

Chinese

for ‘water’ and ‘gold,’ but pegging that to Hai

Shui doesn’t really add

up for me, just because the words and his name are

similar. How about I quote

you about the Chinese connection but not about

Shui?”

“Fair

enough,” said Katie, “but I think the credit

should go to the professors. I’ll

give you their numbers if you like.”

“And

that won’t compromise your story?”

“John,

I haven’t got much of a story yet. I’m not doing a

scholarly paper on the

painting. I’m

seeing where all this goes

and where it ends up. You’re reporting the news.”

“Well,

thank you for that. Let’s keep in touch. I’ll let

you know if I hear anything

from the mystery woman.”

“I

don’t suppose the mystery woman will speak to me?”

“That

I doubt. She said she was only speaking to me at

this point.”

“Well,

with all due respect,” said Katie, “why is she

telling only Art Today

rather than first go to the New York

Times or the Wall Street

Journal?”

“I

don’t know and I don’t ask. As long as Art

Today keeps breaking these stories, I’m

happy. I’m

sure she knows how to reach the Times and

the Journal—”

“—And

McClure’s,”

Katie inserted.

“And

McClure’s. They’ll

all stay

titillated without any inside access, which sure

makes me look like the big

cheese in the art media. I can live with that.”

© John Mariani, 2016

❖❖❖

Ricasoli Chianti Gran Selezione

By

John Mariani

More

than once I’ve declared that Chianti would be

my desert

island choice for a wine I could drink

everyday with pleasure and considerable

variety. Here are a few basic facts about

Chianti in the third decade of the

21st century:

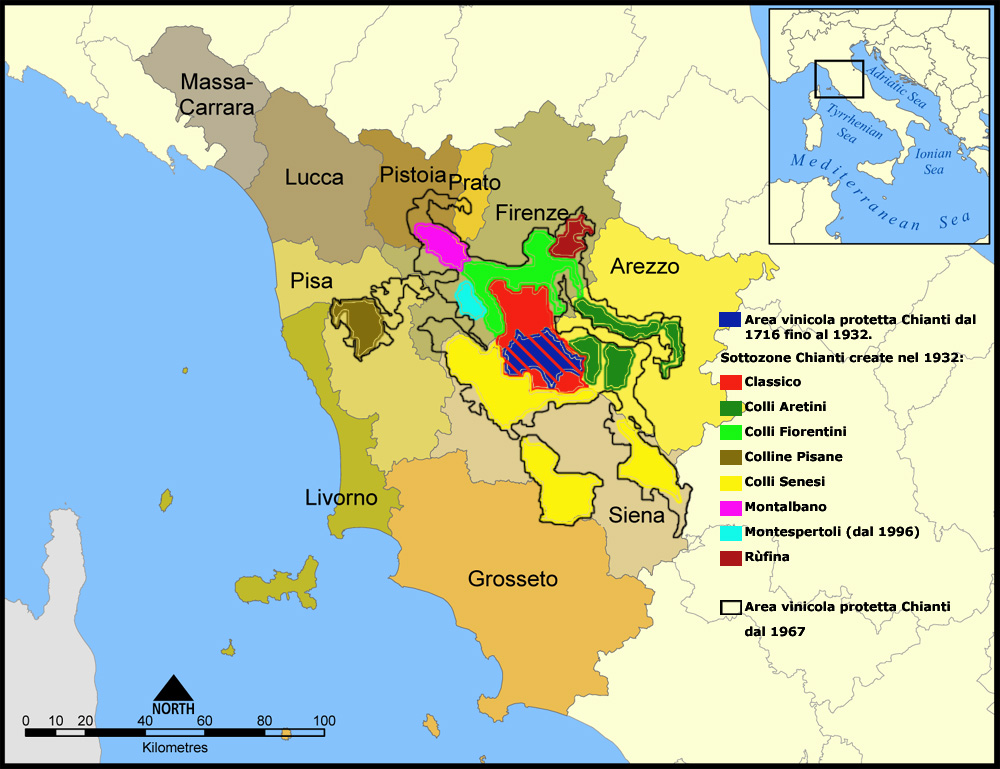

— Chianti is an

appellation under Italian wine laws for a

topographical region with eight

distinct zones, with Chianti Classico the best

known (and most promoted),

although Italian wine laws, rather too

liberally, now grant the prestigious

DOCG appellation to both Chianti Classico and

Chianti.

— There are now 515

vine

growers in the Chianti Classico region, the

majority of them both growing

grapes and vinifying them into wine. Forty

percent are certified organic. There

are only 7,000 hectares of vineyards

representing less than 15% of its total

surface in Tuscany.

— Chianti Classico DOCG

must be produced with Sangiovese (minimum 80% up

to 100%) and, as an option,

other red varieties (up to 20%). Among the

latter, there are the indigenous

ones (Canaiolo, Colorino, Mammolo, Malvasia

Nera, Pugnitello and Foglia Tonda),

and the international ones (Cabernet Sauvignon,

Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Syrah

and Petit Verdot). White grape varieties, once

permitted, have not been since

2006.

— For this century the U.S. has been the top Chianti Classico market. Over one-third of Chianti Classico bottles are sold in America; second place is Italy itself.

Chianti Classico (hereafter “CC”) is a very old appellation, dating to 1716, when the territory was delimited, for the first time, by an edict of the Grand Duke Cosimo III of the Medici family, fixing the borders of the production area. Many of the best known producers, like Antinori, Ruffino, Querciabella, Fontodi, Castello di Volpaia and Badia a Coltibuono, have a significant grasp of the world market.

Barone Ricasoli Castello di Brolio is

not only the oldest winery

in Italy (since 1141), but the composition

“recipe” of Chianti was established

by Ricasoli (left) as of 1872. The estate

itself, with overlapping Romanesque,

Neo-Gothic and 19th century Tuscan architecture,

is located on a spread of more than 1,200 hectares

that include 240 hectares of vineyards and 26 of

olive groves in the commune of

Gaiole. (It is a beautiful castle you can visit

year-round, except January,

with an excellent Tuscan restaurant.)

Barone Ricasoli Castello di Brolio is

not only the oldest winery

in Italy (since 1141), but the composition

“recipe” of Chianti was established

by Ricasoli (left) as of 1872. The estate

itself, with overlapping Romanesque,

Neo-Gothic and 19th century Tuscan architecture,

is located on a spread of more than 1,200 hectares

that include 240 hectares of vineyards and 26 of

olive groves in the commune of

Gaiole. (It is a beautiful castle you can visit

year-round, except January,

with an excellent Tuscan restaurant.)Like most of its competing CC estates, Ricasoli has been committed to sustainability and biodiversity, with 70% covered with woods and Mediterranean scrub they characterize as a “huge green lung.”

Ricasoli produces a wide array of CCs (as well as some

white wine), and its

Gran Selezione series is not only its

top-of-the-line bottlings but readily compares

with many so-called Super

Tuscans in the market without resorting to that

specious name.

white wine), and its

Gran Selezione series is not only its

top-of-the-line bottlings but readily compares

with many so-called Super

Tuscans in the market without resorting to that

specious name. Castello di Brolio Chianti

Classico Gran Selezione 2018 ($70)—Is a blend of a

minimum

of 90% Sangiovese, with 5% Cabernet Sauvignon to

give it a bit more tannin and

5% Petit Verdot for richer fruit. This is the

estate’s flagship wine, created

from a selection of estate-grown grapes from

different sections, produced only

in the best years. It certainly compares well

with some of the finest wines

from Bolgheri.

CeniPrimo Chianti Classico Gran

Selezione 2018 ($85)—This is 100% Sangiovese from

fruit grown in the southern

valley of the River Arbia,

which

has a complex soil composition of silty

deposits and few stones, with some clay deposits

and limestone. At 14.5%

alcohol, this is at the edge of where CCs are

balanced and is the brawniest of

Ricasoli’s CCs, which will still improve within

the next three to five years.

Colledilà

Gran Selezione 2018 ($85)—Also

100%

Sangiovese from a terroir quite different, with

more clay and limestone rich in

calcium carbonate and poor in organic material.

It spent 22

months in 500-litre tonneaux, of

which 30% new and 70% second passage. Its

13.5% alcohol is perfect to show both its CC

traditions and its modern

elegance.

Roncicone Gran Selezione 2018 ($85) —Another 100% Sangiovese,

from soil rich in sandy marine deposits and sea-smoothed

stones with substantial organic

matter content. This gives a minerality to the

wine that makes it multi-layered

in its flavors, with restrained fruit. The 14%

alcohol bolsters its elements

without pushing any out of synch.

❖❖❖

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las

Vegas JOHN CURTAS has been covering

the Las Vegas food and restaurant scene

since 1995. He is the co-author of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las

Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

Eating Las

Vegas JOHN CURTAS has been covering

the Las Vegas food and restaurant scene

since 1995. He is the co-author of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las

Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher

Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish.

Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2022