MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

May

22, 2022

NEWSLETTER

ARCHIVE

_NRFPT_02.jpg)

Mel Ferrer, Erroll Flynn, Ava Gardner and Eddie Albert in "The Sun Also Rises" (1957)

❖❖❖

IN THIS ISSUE

THE BEST RESTAURANTS IN THE WORLD,

Part One

By John A. Curtas

NEW YORK CORNER

HAWKSMOOR

By John Mariani

ANOTHER VERMEER

CHAPTER TWENTY

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

THE WINES OF LURETTA

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

THE BEST RESTAURANTS IN THE WORLD,

Part One

By John A. Curtas

Baguette and Butter at La Tour d'Argent

If

you take it as a given that French restaurants

are the best in the world, it only stands to

reason that the best restaurant in the world

will be in France.

Don't get your

panties in a bunch, I'm not here to dismiss the

cuisines of entire countries—only to point out

that, like sushi, Mexican street food and pasta,

the places where certain foods began are generally

where you will find the highest elevation of the

art. And Paris, in case you've forgotten, is where the

modern restaurant was born in the latter half

of the 18th Century.

Of course, the "best" of anything is a

conceit and highly subjective. Measuring a

"winner" or "the best" of anything is a nice

parlor game, but ultimately a waste of time unless

there's a stopwatch involved. Whoever wins these

accolades usually comes down to who got fawned

over the most in a few influential

publications—not who objectively gives diners the

best food and drink experience. Anyone who thinks

the several hundred voters who weigh in on these

awards have actually eaten at the places they vote

for as "the best restaurant in the world" (as

opposed to forming their opinions based upon

reading accounts of the few who have) has rocks in

their head.

Of course, the "best" of anything is a

conceit and highly subjective. Measuring a

"winner" or "the best" of anything is a nice

parlor game, but ultimately a waste of time unless

there's a stopwatch involved. Whoever wins these

accolades usually comes down to who got fawned

over the most in a few influential

publications—not who objectively gives diners the

best food and drink experience. Anyone who thinks

the several hundred voters who weigh in on these

awards have actually eaten at the places they vote

for as "the best restaurant in the world" (as

opposed to forming their opinions based upon

reading accounts of the few who have) has rocks in

their head.

"Awards" of this sort are simply a way to

give a deceptively false measuring stick to those

who don't know much about a subject. Subjectivity

disguised as objectivity, all in the name of

marketing to those with more money than taste.

Same as with wine scores and Oscar nominations.

The rich need these adjudications to convince

themselves they're doing the right thing, and "The

"World's 50 Best Restaurants" is there for them.

As Hemingway puts it in "A Moveable Feast":

The rich came led by the pilot

fish. A year earlier they never would have come.

There was no certainty then.

Back when El

Bulli (right) was garnering these

awards (and I was voting on them), I heard from

several colleagues who ate there, and what they

described was more of a soul-deadening food slog

(an edible marathon, if you will) than an actual  pleasant experience. A close

friend (who also happens to be a chef) told me he

stopped counting after 40 courses of (often)

indecipherable eats and was looking for the door

two hours before the ordeal ended. The trouble

was, he said, there was literally no place to

go—El Bulli near, Roses, Spain, being, literally,

in the middle of nowhere. But Ferran Adrià (like

Thomas Keller of The French Laundry before him and

Grant Achatz of Alinea and René Redzepi of Noma

after), was anointed because, as in Hollywood, a

few influential folks decided they were to be on

the au courant bucket

list-of-the-moment, and woe be to anyone in

the hustings to question these lordly judgments.

pleasant experience. A close

friend (who also happens to be a chef) told me he

stopped counting after 40 courses of (often)

indecipherable eats and was looking for the door

two hours before the ordeal ended. The trouble

was, he said, there was literally no place to

go—El Bulli near, Roses, Spain, being, literally,

in the middle of nowhere. But Ferran Adrià (like

Thomas Keller of The French Laundry before him and

Grant Achatz of Alinea and René Redzepi of Noma

after), was anointed because, as in Hollywood, a

few influential folks decided they were to be on

the au courant bucket

list-of-the-moment, and woe be to anyone in

the hustings to question these lordly judgments.

Because of this nonsense, we've been

saddled with the tyranny of the tasting menu for

twenty-five years of disguised foods and tasteless

foams and edible vegetation concoctions designed

more for ground cover than actual eating. As far

as I can tell, neither molecular cuisine nor eating

tree bark and live ants has caught on in the real

world— beyond trophy-hunting gastronauts who swoon

for the "next big thing" the way the fashion press

promotes outlandish threads to grab attention.

Shrimp and ants at NOMA

Which brings us back to

France. More particularly, French restaurants and

what makes them so special. Let's begin with food

that looks like real food, not someone's idea of

playing with their food, or trying to turn it into

something it isn't. This cooking philosophy alone

separates fine French cuisine from the pretenders

and gives it a confidence few restaurants in the

world can match.

Which brings us back to

France. More particularly, French restaurants and

what makes them so special. Let's begin with food

that looks like real food, not someone's idea of

playing with their food, or trying to turn it into

something it isn't. This cooking philosophy alone

separates fine French cuisine from the pretenders

and gives it a confidence few restaurants in the

world can match.

For one thing,

there's a naturalness

to restaurants in France that comes from the

French having invented the game.

Unlike many who play for the "world's

best" stakes, nothing about them ever feels

forced, least of all the cooking. With

four-hundred years to get it right, French

restaurants display everything from the napery to

the stemware with an insouciant aplomb that is the

gold standard.

You don't have to instruct the French how

to run a restaurant any more than you must teach a

fish how to swim. Or at least that's how it

appears when you're in the midst of one of these

unforgettable meals, because, to repeat, they've

been perfecting things for four hundred years. Everything

from the amuse

bouche to the petit fours

have been carefully honed to put you at ease with

being your best self at the table.

Having been at this gig for a while, I'm

perfectly aware

that the death of fine French

dining,

and intensive care service accompanying it, has been

announced about every third year for the past

thirty. I'm not buying any of it. When you go to

France (be it Paris or out in the provinces), the

food is just as glorified, the service rituals

just as precise and the pomp and circumstance just

as beautifully choreographed as it was fifty years

ago. The fact that younger diners/writers see this

form of civilized dining as a hidebound, time-warp

does not detract from its prominence in the

country that invented it.

Whether you're in Tokyo or Copenhagen, the

style and performative aspects of big deal meals

still takes their cues from the French. Only

elaborate Mandarin banquets or the

hyper-seasonality of a Japanese kaiseki dinner match

the

formality and structure of haute cuisine.

These forms of highly stylized

dining follow a path straight up the food chain.

There are rules and they are there for a reason,

usually having to do with how you will taste and

digest what is placed before you. Light before

heavy; raw before cooked; simple before complex --

you get the picture.

You usually begin with something fished

directly from the sea. Oysters and other shellfish

are a natural match, as is a shrimp cocktail. (A

good old-fashioned American steakhouse has more in

common, with high falutin' French than people

realize.) Their natural salinity stimulates

the appetite without weighing you down.

Man's evolution into more cultivated forms

of eating is represented by bread, as is the

domestication of animals by the butter slathered

upon it. If you want to stretch the symbolism even

further, look at olive oil and the fermentation of

wine and beer as representing mankind's earliest

bending of agriculture to his edible wants and

needs.

From there things get

more elaborate, depending on whether you want to

go the seafood, wild game or domesticated fowl

route. Vegetables get their intermezzo by using

salad greens as a scrub for the stomach to help

digest everything that precedes them. The French

think eating a salad at the start of a meal is

stupid, and it is. You finish of course with cheese—what

Clifton

Fadiman called "milk's leap toward

immortality"—and

then with the most refined of all

foods: sugar and flour and all the wonderful

things that can be done with them. A great French

meal is thus every bit the homage to nature as

Japanese kaiseki, albeit with a lot more

wine and creme brûlée.

From there things get

more elaborate, depending on whether you want to

go the seafood, wild game or domesticated fowl

route. Vegetables get their intermezzo by using

salad greens as a scrub for the stomach to help

digest everything that precedes them. The French

think eating a salad at the start of a meal is

stupid, and it is. You finish of course with cheese—what

Clifton

Fadiman called "milk's leap toward

immortality"—and

then with the most refined of all

foods: sugar and flour and all the wonderful

things that can be done with them. A great French

meal is thus every bit the homage to nature as

Japanese kaiseki, albeit with a lot more

wine and creme brûlée.

As I've written before, French food is

about the extraction and intensification of

flavor. Unlike Japanese and Italians, a French

cook looks at an ingredient (be it asparagus,

seafood, or meat) and asks himself: "Self, how can

I make this thing taste more like itself." All the

simmering, searing, pressing, and sieving in a

French kitchen is as far a cry from leaving nature

well enough alone as an opera is from the warble

of a songbird.

With this in mind, we set our sights on two

iconic Parisian restaurants: one, as old-fashioned

as you can get, and the other a more modern take

on the cuisine, by one of its most celebrated

chefs. Together, they represent the apotheosis of

the restaurant arts. They also signify why, no

matter what some critics say, the French still

rule the roost. Blessedly, there is no chance of

encountering Finnish reindeer moss at either of

them.

LA TOUR D’ARGENT

LA TOUR D’ARGENT

If experience is any

measure of perfection, then The Tower of Money

should win "best restaurant in the world" every

year, because no one has been serving food this

fine, for this long, in this grand a setting.

A restaurant in one form or another has been

running at this location since before the Three

Musketeers were swashing their buckles. What began

as an elegant inn near the wine docks of Paris in

1582 soon enough was playing host to everyone from

royalty to Cardinal Richelieu. It is claimed that

the use of the fork in France began in the late

1500s at an early incarnation of "The Tower of

Silver," with Henry IV adopting the utensil to

keep his cuffs clean. Apocryphal or not, what is

certainly true is that the king bestowed upon the

La Tour its crest, which is still there today.

History, of course, provides the

foundation, and the setting continues to provide a

"wow" factor unmatched by all but a handful of

restaurants in the world. No place but here can

you dine with the ghosts of Louis XIV, Winston

Churchill, and Sarah Bernhardt, all while seeming

to float above Paris on this open door to the

city's past—all of it available to anyone with the

argent to book a table.

But the proof is in the cooking, which on

our last two visits has been as awesome as the

view. It's no secret that the glory had started to fade twenty years ago, and that

Michelin, self-appointed the arbiter of all things

important in the French food world, had taken

notice, and not in a good way.

had started to fade twenty years ago, and that

Michelin, self-appointed the arbiter of all things

important in the French food world, had taken

notice, and not in a good way.

A reboot of sorts was announced over five

years ago, and by the time we visited in 2019, the

kitchen was performing at a Michelin two-star

level at the very least. Independent of the view,

the service, and the iconic wine program, the

cooking and presentation were well-nigh perfect.

It was all you want from this cuisine: focused,

intense flavors put together with impeccable

technique and an almost scientific attention to

detail.

Fréderic Delair carving a canard au sang

When we returned this

past winter, things seemed be have gotten even

better. This time we showed up with a party of

six. It was a busy lunch, filled with local

gourmets and some obvious big business types, but

also a smattering of tourists who like us had to

keep picking their jaws up off the table as

spectacle of Paris and its finest French food was

spread before them.

I have never been to La Tour at night, but

for my money, lunch is the way to go. The food is

unchanged (lunch specials are offered, but you can

order off the dinner menu and we did), and the

sight of the Seine stretching beneath you and

Notre Dame and the Île de la Cité in the distance

are worth the admission all by themselves. I

suppose the ideal time to dine here would be

arranging for a table at dusk, so you could see

the lights of Paris come alive in all their

blazing glory. But as I've argued before, lunch

has always been the ticket for us when we want to

eat and drink ourselves silly in a fine French

restaurant.

There's nothing silly, of course, about the

food. This is serious stuff, but there's nothing

stuffy about it, despite its pedigree—French

service having retired the snootiness-thing

decades ago. Meaning, if you show up properly

dressed and are well-behaved, they are friendly to

a fault.

There's nothing silly, of course, about the

food. This is serious stuff, but there's nothing

stuffy about it, despite its pedigree—French

service having retired the snootiness-thing

decades ago. Meaning, if you show up properly

dressed and are well-behaved, they are friendly to

a fault.

Credit for that must lie with owner André Terrail

(left), the third generation of the family

to be at the helm. (The Terrails have owned the

restaurant since 1911.) Since taking over a few

years before his father Claude's death in 'o6,

Terrail has kept the historical provenance of his venerated birthright  intact,

upgrading the cuisine while still managing to keep

the whole operation true to its roots. No easy

feat that. We don't know what the problems were

twenty years ago, but on our last two visits, we

didn't see any missteps, either on the plate or in

the service. And what appeared before us was every

bit as stunning as any Michelin 3-star meal we've

had in Paris or elsewhere.

intact,

upgrading the cuisine while still managing to keep

the whole operation true to its roots. No easy

feat that. We don't know what the problems were

twenty years ago, but on our last two visits, we

didn't see any missteps, either on the plate or in

the service. And what appeared before us was every

bit as stunning as any Michelin 3-star meal we've

had in Paris or elsewhere.

You take good

bread for granted in Paris, but even by those

lofty standards, this small baguette was a

stunner: perfect

in every respect: a twisted baguette of indelible

yeastiness, perfumed with evidence of deep

fermentation, the outer crunch giving way to

ivory-pale, naturally sweet dough within

that fought back with just the perfect amount

of chew. It and the butter  were

show-stoppers in their own right, and for a brief

minute, they competed with the view for our

attention. We could've eaten four of them (and

they were offered throughout the meal) but

resisted temptation in light of the feast that lay

ahead.

were

show-stoppers in their own right, and for a brief

minute, they competed with the view for our

attention. We could've eaten four of them (and

they were offered throughout the meal) but

resisted temptation in light of the feast that lay

ahead.

Soon thereafter, scoops of truffle-studded

foie gras appeared, deserving of another ovation,

and from there on, the hits just kept on coming: a

classic quenelles de brochet (right)—good

luck finding them anywhere but France these

days—then, a slim, firm rectangle of turbot in a

syrupy beurre blanc, or the more

elaborate sole Cardinale, then followed by a

cheese cart commensurate with this country's

reputation.

The star of the show has been, since the

1890s, the world-famous pressed duck (Caneton

Challandais), served in two courses, the

first with the deepest-colored Béarnaise we've

ever seen; the second helping bathed in the

richest, midnight-brown, duck blood-wine blanket

imaginable (left). Neither sauce did

anything to mitigate the richness of the fowl,

which is, of course, gilding the lily and the

whole point.

We could go on and on about how fabulous

our meal was, but our  raves

would only serve to make you ravenous for

something you cannot have, not for the next ten

months, anyway. Yes, the bad news is the

restaurant is closed for renovations until

February 2023. This saddens us, but not too much

since we don't have plans to return until about

that time next year. In the meantime, the entry

foyer probably could use some sprucing up (since

it looks like it hasn't been touched since 1953),

and we have confidence Terrail won't monkey with

the sixth-floor view, or the skinny little

pamphlet he keeps on hand for the casual wine

drinker.

raves

would only serve to make you ravenous for

something you cannot have, not for the next ten

months, anyway. Yes, the bad news is the

restaurant is closed for renovations until

February 2023. This saddens us, but not too much

since we don't have plans to return until about

that time next year. In the meantime, the entry

foyer probably could use some sprucing up (since

it looks like it hasn't been touched since 1953),

and we have confidence Terrail won't monkey with

the sixth-floor view, or the skinny little

pamphlet he keeps on hand for the casual wine

drinker.

If the measure of a great

restaurant is how much it makes you want to

return, then La Tour D'Argent has ruled the roost

for two hundred years. (Only a masochist ever left

El Bulli saying, "I sure can't wait to get back

here!") Some things never go out of style and La

Tour is one of them. We expect it to stay that way

for another century.

À Bientôt!

Part Two of this article will appear

soon.

❖❖❖

NEW YORK CORNER

HAWKSMOOR

109 East 22nd Street

By John Mariani

I’ve long since given up wondering if New York could possibly absorb another steakhouse, because the question is moot in the face of so many opening on what seems a monthly basis. Most follow the sacrosanct traditions of the New York steakhouse set decades ago, with menus deliberately very similar for the simple reason that those dishes are what guests expect and crave. And they are now the model for steakhouses all over the world.

Hawksmoor

is something of an exception, first for being an

import from the UK, where the first one was opened

in 2006 in London’s East End by founders Will Beckett and Huw Gott.

Second, there are

several items on the menu you won’t find elsewhere

in town. Third, the place eschews the usual design

elements of so many steakhouses by virtue of it

being set within the cavernous space of what was

once the United Charities

Building, gifted in 1893 by wealthy Scotsman John

S. Kennedy. With its majestic 26-foot-high

ceilings, stained glass windows and spreading

archways, the space allows for seating for 146 in

the dining room and 35 at the boisterous bar, with

two private rooms. Indeed, such a huge, echoing

space makes for a very, very loud dining

experience, not helped by the addition of piped-in

pounding bass-and-drums.

Hawksmoor

is something of an exception, first for being an

import from the UK, where the first one was opened

in 2006 in London’s East End by founders Will Beckett and Huw Gott.

Second, there are

several items on the menu you won’t find elsewhere

in town. Third, the place eschews the usual design

elements of so many steakhouses by virtue of it

being set within the cavernous space of what was

once the United Charities

Building, gifted in 1893 by wealthy Scotsman John

S. Kennedy. With its majestic 26-foot-high

ceilings, stained glass windows and spreading

archways, the space allows for seating for 146 in

the dining room and 35 at the boisterous bar, with

two private rooms. Indeed, such a huge, echoing

space makes for a very, very loud dining

experience, not helped by the addition of piped-in

pounding bass-and-drums. Fourth, Hawksmoor differs in its dedication to American farming processes by sourcing hormone-free cattle and biodiversity that promises “the best beef comes from happy cattle.” Whatever.

Upon opening last fall, Hawksmoor served American corn-fed beef (though not graded USDA Prime) but also promoted beef raised wholly on grass, as is the case in the UK and Europe. The reality is that grass-fed cattle never develop the kind of fat marbling that cattle on a corn (or corn-finished) diet acquire. That fat provides flavor pure grass-fed cattle will never have.

Still, on my recent visit, I was told that now most of the cuts on the printed menu are, in fact, finished on corn.

The

grass-fed cuts are listed on a blackboard (by the

ounce), with only so much of a daily supply as they

can get, so they may well run out of them quickly. I

had a 7:15 p.m. reservation, by which time they had

eighty-sixed at least one of those cuts. Which left

me to appreciate all the more the sweet, fatty beefy

quality of the steaks I did sample.

The

grass-fed cuts are listed on a blackboard (by the

ounce), with only so much of a daily supply as they

can get, so they may well run out of them quickly. I

had a 7:15 p.m. reservation, by which time they had

eighty-sixed at least one of those cuts. Which left

me to appreciate all the more the sweet, fatty beefy

quality of the steaks I did sample.You will be advised right off the bat that Hawksmoor’s steaks all rest for 15-20 minutes after leaving the grill, which is no big deal in terms of wait time if you’re enjoying cocktails and the exciting appetizers well worth ordering. There is a rosy-ink steelhead crudo ($22) laced with citrus, ginger and chili, and the half Maine lobster ($30 for about 12 ounces) is succulent, with a rich lavishing of garlic butter. Excellent fat sea

scallops ($26) sit prettily on the shell, though

without the coral (right), and are enhanced

by being cooked over charcoal, with a garlic and

sweet white Port sauce. Most of

all I liked a glass jar of potted beef and bacon

($18), a layer of fat and beef trimmings, a hearty

dish clearly derived from traditional British

cookery; it’s rich and creamy and comes with a

delightful onion gravy and Yorkshire pudding

popovers (sad to say quite soggy).

scallops ($26) sit prettily on the shell, though

without the coral (right), and are enhanced

by being cooked over charcoal, with a garlic and

sweet white Port sauce. Most of

all I liked a glass jar of potted beef and bacon

($18), a layer of fat and beef trimmings, a hearty

dish clearly derived from traditional British

cookery; it’s rich and creamy and comes with a

delightful onion gravy and Yorkshire pudding

popovers (sad to say quite soggy).In addition to those blackboard cuts (which range from $4 to $6 an ounce, so a 15-ounce steak will run about $75), there are nine steak cuts, with sauces extra, and six non-beef options. As noted, we ordered the corn-finished steaks, and they were first-rate in every respect, not least for the char on the exterior and the minerality of the dry-aging process.

The

14-ounce strip steak ($55) was excellent, as was the

carved sirloin on the bone ($4 an ounce). The rump

steak is not just the cheapest cut on the menu at

$32 for 12 ounces, but for my money the most

interesting, not because it has more flavor than the

rest but because it has a fine chewiness and

savoriness of its own you won’t find at other

steakhouses. Every cut, overseen by executive chef

Matt Bernero and delivered by executive grill chef

Paddy Coker, was cooked with obvious care and a

critical sense of timing.

The

14-ounce strip steak ($55) was excellent, as was the

carved sirloin on the bone ($4 an ounce). The rump

steak is not just the cheapest cut on the menu at

$32 for 12 ounces, but for my money the most

interesting, not because it has more flavor than the

rest but because it has a fine chewiness and

savoriness of its own you won’t find at other

steakhouses. Every cut, overseen by executive chef

Matt Bernero and delivered by executive grill chef

Paddy Coker, was cooked with obvious care and a

critical sense of timing.Side dishes like “mash & gravy” ($10) and creamed spinach ($10) were par for the course—they were already out of the butterball potatoes—while the mac & cheese ($10) could have used some spicing up.

Among the desserts, by Carla Henriques, hers is not the only sticky toffee pudding ($14) in town, but it may well be the best, equally matched by a Grand Rocher ($18) of chocolate and hazelnut. For something less sweet, the Meyer lemon “bomb” ($12) with lemon-ripple ice cream will serve well.

The wine list is outstanding in every category, with a judicious selection under $100, and on Mondays “we encourage you to bring your own bottle of wine and we’ll cork it for only $10.”

There is, in fact, a generosity of spirit at Hawksmoor that begins with a very cordial greeting at the front, led by manager Niamh Scott . The waitstaff, however, is hard put because they seemed to be short-handed, which is a problem in restaurants everywhere these days, and you’re likely to have to hail your waiter if you need something.

The London critics of Hawksmoor have owned up to the superiority of its beef to what is traditionally the case in Britain, where thinly sliced beef with pan juices is more usual and corn-fed beef a great rarity. That the founders knew they had to go even further with sourcing American beef for the New York restaurant they have set a self-imposed bar that may be self-limiting. For now, Hawksmoor is unique in New York on several counts and certainly one of the most beautiful new restaurants to open in the city in the past year.

❖❖❖

ANOTHER VERMEER

“I’m beginning to think,” said David, “that the old saying about a great crime being behind a great fortune might be appended to include, behind every great crime there is another great fortune hidden away.”

“So you think Saito would have had the gall to try to buy the Vermeer?”

“Well, if he sold just the van Gogh and the Renoir, he’d have the money, and a grateful art world would applaud him for not burying them in his tomb the way he said he might.”

Katie nodded. “Makes sense. He sells two master paintings, then buys another that had been hidden away for hundreds of years. And it’s a wash, so, if anything, his reputation loses some of its tarnish.”

“Exactly.”

“But then . . . he dies.”

“Well, he was getting up there.”

“But he was not at death’s door, or at least I don’t think he was. Do you think it’s possible Saito may have been, uh, bumped off to keep him out of the Vermeer auction?”

David widened his eyes and spread his palms. “Hey, I had no idea the art world was full of so many crooks and so much money passing around. I don’t think a hit on Saito is out of the question.”

“See, that’s why I need you,” said Katie, jumping up and hugging David. “I just don’t have your devious mind!”

“Flattery accepted,” said David, not wanting her to release her arms around him, but she turned away and said, “So now, somehow or other, we have to find out how or why Saito died. I wonder if there was an autopsy? Do the Japanese do autopsies when their billionaires keel over?”

“I suspect they do.”

“Because I didn’t read anything about a suspicious death in the files.”

“Did you read the Japanese papers?”

Katie sighed. “No, I can’t say I know how to read from right to left. But I do know who might. I’m going to call Professor Lìu. I’ll bet she speaks and writes Japanese.”

Katie picked up the phone and was able to get Prof. Lìu at her office on the Fordham campus.

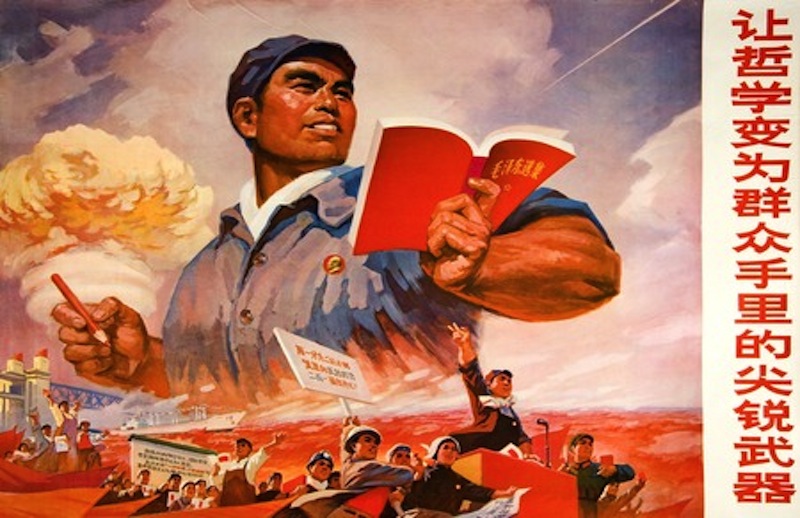

“Your contacts are right about China not

participating in the global art market until now,”

the professor said. “Now, I think it’s possible

that the Chinese may regard a 17th century Dutch

painting as some form of Western decadence

unworthy of being among their Asian

treasures—however decadent they

might be. Except

during that nihilistic Cultural Revolution under

Mao Zedong, when all taint of foreign culture was

to be eliminated, Communist regimes have always

pretended that art collections, like the gold and

silver and jewels in the churches, are to be kept

just to show off how decadent the West really is. It’s

nonsense, of course, but very little was ever

thrown on the fire, so to speak. Same with the

Nazis, although they called the art ‘degenerate.’

They burned books in public but they confiscated

the Rembrandts and Raphaels.”

“Your contacts are right about China not

participating in the global art market until now,”

the professor said. “Now, I think it’s possible

that the Chinese may regard a 17th century Dutch

painting as some form of Western decadence

unworthy of being among their Asian

treasures—however decadent they

might be. Except

during that nihilistic Cultural Revolution under

Mao Zedong, when all taint of foreign culture was

to be eliminated, Communist regimes have always

pretended that art collections, like the gold and

silver and jewels in the churches, are to be kept

just to show off how decadent the West really is. It’s

nonsense, of course, but very little was ever

thrown on the fire, so to speak. Same with the

Nazis, although they called the art ‘degenerate.’

They burned books in public but they confiscated

the Rembrandts and Raphaels.”“By the way, Prof. Lìu,” asked Katie, “do you speak and read Japanese?”

“Fairly well. Both the Chinese and Japanese use kanji ideograms for writing, and the majority mean the same thing in both languages.”

“Well, would it be too much for me to ask if you might help me read Japanese newspaper reports on what was the cause of death of Mr. Saito this year? I couldn’t find anything in the files. My magazine will be happy to pay you for your time and expertise.”

“Believe me, I’d love to help, though at the moment I am hopelessly tied up with work here. They just made me head of the department.”

“Congratulations,” said Katie.

“But you really don’t need me to find what you’re looking for. The New York Public Library has a complete collection of the Japan Times published in English. I’m sure they’ll have what you’re looking for.”

“I never thought of that,” said Katie, smacking her forehead. “Listen, thanks so much. You’ve been incredibly helpful with this story.”

“I’m very interested to see how it turns out,” said Prof. Lìu. “You can take me to lunch some time.”

“Done deal. Whenever you have the time, call me,” said Katie, who thought to herself, “I’ll take her to any Chinese restaurant she’d like,” then thought that was the dumbest thought she’d ever said, like her dates who thought Katie Cavuto would only want to go to an Italian restaurant for dinner.

Katie told David what Prof. Lìu had said, then asked, “Want to sit around the New York Public Library with me for the rest of the day?”

David shrugged. “Sure, why not?” happy that they’d be together in a quiet place, then maybe dinner later.

Katie adored the NYPL—David had only been inside once, while they were working on the Capone article—its nose-in-the-air lion statues guarding the front steps since 1911, the Beaux Arts façade, monumental pillars and staircases, the big room that held millions of index cards with the library’s holdings cataloged by the old Dewey Decimal System. She loved flipping those cards, then writing out her request on a white and blue slip of paper and bringing it to the librarian who would scribble something on it, give Katie a number, and send the slip down a pneumatic tube to be located and sent up on a dumb waiter to one of two vast, ornate Reading Rooms.

David didn’t fully understand Katie’s love of the whole place and process. He always hated going through the police records, always in musty storage, never with anything where it should be. It could take him days to obtain what he was looking for. Here at the NYPL, unless it was crunch time for term papers at the end of a school semester, the requested items came up within minutes, announced by a lighted number on a board to coincide with the one provided by the librarian.

“I never get tired of looking at this room,” said Katie, rolling her eyes from the floor to shelves crammed with tens of thousands of reference books, to the huge windows and ceiling—much in need of restoration—with its trompe l’oeuil painting of clouds. She loved the smell of the room—aging books—almost two city blocks long, the patina of the massive oak work tables and the green and brass lamps on them.

Katie had put in requests for various issues of the Japan Times, starting from the date when Saito had died that spring. Those issues had not yet been bound but were in order.

“Okay, let’s see what we can find,” she whispered to David, turning over the pages for June 3, 1997. “Bingo! Saito’s obituary!”

The article was fairly extensive, given Saito’s notoriety, but it told Katie little about the man’s bio and businesses she hadn’t already culled from other sources. The article began, “Ryoei Saito, whose family had some of the largest financial holdings in Japan, died at the age of 72 after being rushed to Takanawa Hospital after suffering from what appeared to be a heart attack.” Katie then skimmed down, looking for further information on the cause of his death, but there was nothing more, except a notice that “an autopsy was expected to be performed to determine Mr. Saito’s cause of death.”

“Well, that’s no help,” said David. “Maybe there’s a follow-up story on the autopsy, but how are we supposed to find it?”

Katie replied, “We’ll ask one of the librarians at the information desk. They pride themselves on answering the most obscure questions you can throw at them.”

They returned to the catalog room and Katie asked a young bearded librarian if there was any way to find the kind of article she was looking for.

“Let me get you someone who might help,” he said. He walked ten steps to the other side of the desk and brought back a Japanese-American librarian who asked, “How can I help you?”

“I’m looking for a

possible autopsy report on a well-known Japanese

businessman who died this summer,” said Katie. “I

found his obituary in the Japan Times,

which said an autopsy was expected to be done, but

I have no idea if the paper would report on that

or when. Do you have any idea how I can narrow

things down?”

“I’m looking for a

possible autopsy report on a well-known Japanese

businessman who died this summer,” said Katie. “I

found his obituary in the Japan Times,

which said an autopsy was expected to be done, but

I have no idea if the paper would report on that

or when. Do you have any idea how I can narrow

things down?”The librarian shrugged as if she’d just been asked to locate a copy of Huckleberry Finn, then said, “The Japanese authorities are very good and very timely about autopsies, and they’d issue their findings within a month of the autopsy being done. So I’d look in issues of the paper from, say, June 15 through July 15. If you don’t find it by then, the paper was unlikely to have reported on it.”

“And if they did not report on it,” asked Katie, “would that suggest there was nothing unusual in the autopsy?”

“I would think so. In which case, you might have to call the hospital, assuming they’d give out such information. The Japanese keep information like that very private. We do have a directory of Tokyo hospitals if you want to take down the number.”

Katie and David thanked the librarian, who told them where to find the directory, and they headed back to the Reading Room with a new number.

David was impressed. “This place is amazing. They’ve got everything in here, don’t they?”

“Pretty much,” said Katie, “or they’ll tell you where to find it. So, let’s first try to see if the newspaper covered the autopsy.”

“God, I hope so. I’d hate to have to drag it out of a Tokyo hospital.”

“Maybe Kiley at Interpol can help out with that?”

“I’d have to really convince him that there’s a good reason to do so, and he hasn’t been too keen on any of our theories so far.”

David explained that there were two types of autopsies: A forensic autopsy is used to determine the cause of death that might have been from an accident, suicide or homicide.

“With a forensic, they usually test for toxic substances, maybe poison,” said David. “A clinical autopsy is done more to find out more about a disease or condition. You usually need permission from the patient’s family.”

“Well, let’s see if there’s anything in the newspaper,” said Katie, who was able to get six issues at a time from the library stacks. “You take three and I’ll take three.”

Three dozen issues and two hours later Katie and David had found nothing. They looked blankly at each other.

“What do we do now?” said Katie.

“How about asking that Chinese professor of yours to call the hospital? You said she speaks Japanese.”

“Yes, but she’s a history professor not a physician.”

“What about your father? He’s a district attorney.”

“I can’t just ask him to call a hospital in Tokyo out of the blue and ask for an autopsy if it’s not related to something he’s working on. He’d never do that.”

David sighed and said, “Well, let me get out my little black book of cop friends and see if I can make contact.”

“You have contacts in the Japanese police department?”

“Well, they don’t really have an equivalent of our F.B.I., but when I was working on the New York mobs we’d occasionally make inquiries with the Japanese police about any connections our mobs had with their mobs. It’s worth a shot. I wonder what time it is in Tokyo.”

Katie checked her computer and found that it was five p.m. in New York would be ten a.m. in Tokyo.

“Perfect. I’ll call when I get home in an hour.”

“Who will you call?”

“I remember there was this very smart detective assigned to the mob squad. Name was Kato.”

“Like that dopey guy who lived on O.J. Simpson’s estate?”

“I was thinking more like the Green Hornet’s sidekick.”

“Who?”

“The Green Hornet? Masked crime fighter. Kato was his partner. Matter of fact, Bruce Lee played him on a TV show back in the ’60s.”

“Before my time,” said Katie.

“Anyway, Kato Yamashita was a crack detective and was very helpful when my department needed info on the yakuza mobs. I’ll call him when I get home.”

That killed David’s idea of having dinner with Katie, but he was feeling some of old adrenalin from when he was a cop on a case, and he wanted to act on his hunch as soon as possible.

Yamashita’s direct phone number was still in David’s police address book, and, with the help of an international operator, he got through to the Tokyo detective in his office. After refreshing his colleague’s memory as to who he was—it had been five years since they’d last spoken—David said he was now retired but working on a “case.”

Yamashita asked, “I’m sorry, Detective Greco”—using his former rank to show respect—“if you are retired from the New York police, does that mean you are a private detective working on a case?”

David knew immediately he had stumbled by calling it a case; he should have said project, because there was no case, official or otherwise.

“No, I’m actually retired but I’ve been helping an American journalist with a story about the international art market, and there is a figure well known in Japan, by the name of Ryoei Saito, whose recent death may bear on the story.”

“Yes, I know of Mr. Saito. He was a very wealthy businessman.”

“And from what I can gather, a crook.”

“Yes, he was tried and convicted. But because of ill health he never went to prison.”

“Right,” said David, happy that his colleague knew of Saito. “So, here’s what I’m interested in. How exactly did he die? The Japan Times said it was probably a heart attack and an autopsy was to be performed, but I can’t find out what the results were.”

“And you would like my office to inspect the autopsy report?”

David didn’t like Yamashita’s using “my office” instead of “me.” He was going by the book.

“Well, if that was at all possible, Detective Yamashita, it would be of enormous help.”

David heard nothing on the line, thinking the connection had been broken.

“Detective Yamashita? Are you there?”

“Yes. I am thinking.” Then, “I am so sorry, Detective Greco, but it is just not something my office can do. If this were an open case and had international importance, and, if this was an official inquiry by a New York police officer, my office would try to do something. But under the circumstances, I am afraid I cannot grant your request. I hope you understand.”

“I do,” said David. “I do. I was just maybe hoping you might do it out of what we call professional courtesy, but I realize I cannot ask that of you under the circumstances.”

“If things were different, I assure you I would try to help.”

There was nothing more to say, so David said thanks and even “Sayonara,” hoping he got the word for “goodbye” right. “Back to square one,” he muttered, then called Katie to tell her he’d struck out.

❖❖❖

THE WINES OF LURETTA

By John Mariani

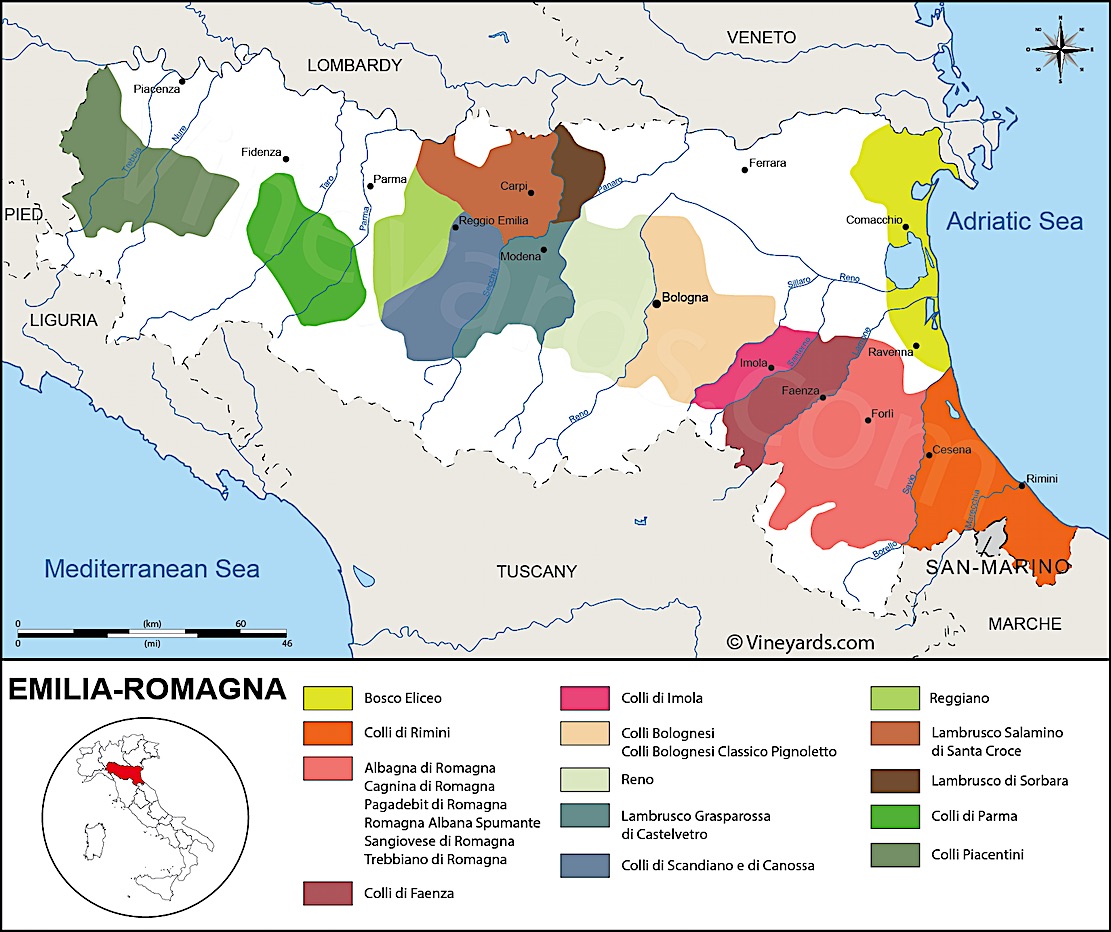

While the food of Emilia-Romagna, centered by Bologna, is considered some of the most sumptuous in Italy, its reputation as a wine region has lagged well behind others like Piedmont, Tuscany and Campania. Known primarily for its sparkling Lambruscos, which can be as cloyingly sweet as Hawaiian Punch, Emilia-Romagna’s only other familiar wine is Albana di Romagna. One winery, however, located in Piacenza, has been as forward-looking as any in Italy. Over dinner in New York I interviewed Lucio Salamini, owner of Luretta-Castello di Momeliano, which was only founded as of 1988, which now make a wide variety of non-traditional DOP wines.

Your estate is nearly half a century old, located in Piacenza in Emilia-Romagna, which has not had a reputation for fine wines. How have you worked to overcome the image that was set by cheap Lambrusco?

Piacenza is still an uncharted territory for many. It is part of Emilia Romagna, but it is a very distinct province from the others. Traditionally, we at Luretta do not make Lambrusco; instead we craft the Gutturnio, a blend of two grapes combined to obtain a perfect red to match our local food. We have hillside vineyards, like those of the major Italian wine regions, not the valley-floor viticulture that characterizes the area of Lambrusco di Parma, Modena and Reggio. In terms of fine winemaking, nowadays we’re living our little renaissance, a moment of redemption from our past history.

In the past, the oenological

research has always been scarce in our territory, and

this has prevented the development of the territory

itself. This is for two main reasons: starting from

the beginning of 1900, Piacenza had always been a

famous area for table grape production, rather than

wine grapes, which was also strongly supported by the

Fascist government that selected Piacenza as the city

to host the popular table grapes fair and helped the

farmers of the area both in the production and in the

export of this product. But within a few decades, in

the ‘50s, the soils of Southern Italy proved to be

more suited for wine grapes, so the vineyards of table

grapes in Piacenza began to be ex-planted and were

replaced by wine grapes that, until then, had been

marginal. At the same time, just a few years after,

the Italian economic boom of the ‘60s saw the

rise of the city of Milan, which is only 30 miles from

Piacenza. The number of workers who came to Milan from

all over the country created a strong demand for

low-priced table wine. At the time there was no meal

without wine for these new workers who until then only

knew the work in the fields. Piacenza had adapted to

produce wine grapes very well: an economical wine with

a medium-low quality. In fact, it was not necessary to

do qualitative research at a time when for the most

important thing was to contain costs to produce a

product for the less affluent classes.

In the past, the oenological

research has always been scarce in our territory, and

this has prevented the development of the territory

itself. This is for two main reasons: starting from

the beginning of 1900, Piacenza had always been a

famous area for table grape production, rather than

wine grapes, which was also strongly supported by the

Fascist government that selected Piacenza as the city

to host the popular table grapes fair and helped the

farmers of the area both in the production and in the

export of this product. But within a few decades, in

the ‘50s, the soils of Southern Italy proved to be

more suited for wine grapes, so the vineyards of table

grapes in Piacenza began to be ex-planted and were

replaced by wine grapes that, until then, had been

marginal. At the same time, just a few years after,

the Italian economic boom of the ‘60s saw the

rise of the city of Milan, which is only 30 miles from

Piacenza. The number of workers who came to Milan from

all over the country created a strong demand for

low-priced table wine. At the time there was no meal

without wine for these new workers who until then only

knew the work in the fields. Piacenza had adapted to

produce wine grapes very well: an economical wine with

a medium-low quality. In fact, it was not necessary to

do qualitative research at a time when for the most

important thing was to contain costs to produce a

product for the less affluent classes. After the 1984 methanol scandal, the so-called Italian "wine renaissance" also hit Piacenza, and little by little, even in our province, the search for quality began. Some companies, including Luretta, have believed in the potential of the territory since then and are incessantly working to enhance it by producing wine of international profile and height. The number of quality bottles crafted are unfortunately still low compared to the volume of wine produced in the area, but we're very committed to communicate and reflect the incredible potential of the Piacenza hills.

Describe the terroir of your estate in the Colli Piacentini.

The native vines are planted in the vineyards closer to the valley, around 820 feet above sea level, characterized by the "Terre rosse antiche" (old red soil) loaded with red clay. The international vines, on the other hand, are planted in vineyards ranging from an altitude of 800 feet to 1,400 feet in the lower Apennines, characterized by a greater concentration of limestone. Most of the vineyards are located within the small Val Luretta that gives the name to our company. They are characterized by a temperate microclimate, protected from spring rains, frosts, summer heat waves and large concentrations of humidity thanks to the constant air flow that characterizes it.

You are an organic farm. Is it biodynamic and, if so, in what way?

We produce organic wines, which means no use of pesticides, no chemical fertilizers, no irrigation, except in case of extreme drought, and no synthetic curative products that enter the plant's circulation, but only copper and sulfur-based defense products. In the cellar, I use only products allowed by the EU organic wine regulation.

You say that your Cabernet Sauvignon grapes are smaller but with thicker skins. What does this produce in the wine?

The fruit produced by organic farming is usually "uglier" but tastier. And the tastier the fruit, the easier it is to make a good glass of wine. Opposite to what is instinctive to think, the most important elements to produce good wine are in the skin of the grape, and not in its pulp, which is mostly made up of water. Therefore, the smaller the grape is, the higher the percentage of peel in the juice is, which results in a tastier juice.

Your Principessa in a 100% Chardonnay in the “classic method,” as in Champagne. How does it differ from Lambrusco in that respect?

Unlike the world of soft drinks, in wine you cannot add CO2, which must be naturally produced by the wine itself through the action of yeasts that transform sugar into alcohol and CO2. The two methods mainly used to obtain this result are the Charmat Method, where fermentation takes place in large containers, used for almost all the production of sparkling wines such as Gutturnio Lambrusco, Prosecco etc., and the Classic Method, or Méthode Champenoise, where the refermentation takes place in each bottle, which is then "cleaned" of yeast residuates through the rémuage and disgorgement phases. This is used for Champagne as well as for my sparkling wines, including the Princessa. I would like to say, though, that this distinction is only indicative; there are in fact excellent proseccos obtained with the Classic Method as well as excellent Lambrusco like that of my friends from the Cantina Della Volta in Bomporto.

Principessa ages on the lees for 18 months, which is more than the minimum of basic Champagnes, though not as long as for vintage cuvees at 36 months. How did you decide on your aging length?

With my wine Principessa, I work on an aging bottling that goes from 18 up to 24 months on the lees, in order to infuse complexity to the wine without making it too austere. We do not want to exceed the 24 months duration because the philosophy of Principessa is to be a fresh and fruity drink, not too complex, not too elitarian. This wine wants to pay homage to the tradition of the easy sparkling drinks of my area. Despite the greater complexity of the Classic Method, we want a sense of pleasantness to be the heart of this product.

Your dry Chardonnay, Selin dl’Armari, is aged for nine months in barriques. New oak? French oak? Since Chardonnay is a grape that is kind of a blank canvas, can you describe its bouquet and flavor?

Selin is my favorite wine, my personal project and a labor of love. It is produced with the grapes of a single vineyard, which has the same name as the wine. The field where the vineyard is located has always been called "Armari" ("closet" in English), and the vineyard is located on the hill of this field, which is shaped like a saddle, "selin" in my dialect. I have a passion for white wines and for white wines made with the use of wood, in particular. For Selin, I use only new 60-gallon Burgundy French oak barriques (my favorite barrel producer is François Frères), and I choose low toasting in order to reduce the smoky scents and enhance those of butter instead. The wine ferments the first two days in the stainless steel tank and then is transferred to the wood, where the fermentation ends, and then remains in refinement for a period ranging from 8 to 11 months, depending on the harvest. The lees are kept in suspension through weekly bâtonnages that confer body and roundness to the wine. In the August following the harvest, the wine is bottled and it rests for another 9 months. It goes on the market the following May, 20 months after the harvest. Selin dl'Armari's taste is rich with hints of butter on the nose with a great sensation of sweet white flowers such as acacia. In the mouth, the wine enters opulently, rich with sweet tannins from the wood, and then it releases the flavor and minerality typical of our soil. It is a very "Italian" Chardonnay, with the fatness of the fruit ripened in the warm climates of our hills prevailing over the acidity and nervous tones of areas such as Burgundy. It is more yellow than green, and it has more power than finesse. Only for this wine, we keep in the winery a magnum of each vintage, so customers can order the current vintage in the bottle and old vintages of their preference in magnum format, since 1999, the first year of production.

Malvasia is not a grape well known to most wine lovers, and is probably best known as the sweet passito from Lipari. Yours, called Bocca di Rosa, is delightfully aromatic but there is only a faint hint of sweetness. How do you vinify? What does the name mean?

In Italy there are 18 different types of Malvasia. The one of Piacenza is the Aromatic Malvasia of Candia and it can only be produced in our province. It has notes very similar to Muscat. In particular, the hints of acacia and elderberry deceive the taster who expects a wine with a sugary residue, which is instead a dry wine.The grapes are harvested completely ripe, when the grapes in the bunch are almost brown, cooled to 42° F, de-stemmed, then placed in the press. There it is left in skin contact for 12 hours, then softly pressed, separating the juice from the skins. This maceration brings color as well as a little tannin. The fermentation takes place in steel, and, in the March following the harvest, it is bottled. At this point, it rests in the bottle for at least 6 months before going on the market, during which the primary aromas of fruit and flowers begin to slightly evolve into balsamic and dry grass scents. The name Boca di Rosa, in fact, which means "mouth of rose, or taste of rose,” recalls

these scents.

these scents.Is Puck, your blend of 70% Cabernet Sauvignon and 30% Barbera, named after Shakespeare's elfish character in A Midsummer Night's Dream? It is never aged in wood, only stainless steel. Why?

During the lockdown time, I thought of creating a simple, light-hearted and irreverent wine. Just like the Shakespearean elf, after whom the wine is named. A wine that makes fun of all my austere, wood-made red wines! A light, fresh one. Only steel and concrete, without complexity but based on the fruit and the flower. And with screw caps, which in Italy is almost impossible to communicate to the market! A fresh, simple and irreverent drink totally focused on pleasantness and immediacy, without many evolutions and complexities.

Most Italian wineries focus on a very few varietals, like Sangiovese in Tuscany and Nebbiolo in Piedmont, yet you have fifteen different wines in your portfolio. Why so much diversity?

As I said before, Piacenza is a rough gem to be discovered. Anyone who has a vineyard in Barolo or Montalcino already knows what to do. We didn't know, and so, instead, we experimented, we embraced different paths. Many experiments have been negative and we have abandoned those roads. In other cases, we decided to follow their evolution, trying to understand together the true vocation of the territory.

What is the price range of your 15 wines?

In the U.S., they go from $23 to $50.

Are most of your wines sold in Italy or exported? How much goes to the U.S.? Has the war in eastern Europe affected sales of Italian wines?

I sell 60% in Italy and the rest abroad, mainly to European markets. I also sell to China, Japan and Malaysia. In recent years, I have looked to the markets of North America because I find them very sophisticated and attentive to unique and different taste profiles. The war had no effect on the European wine market itself, though it has had an effect on the procurement of materials. Ukraine was a large producer of paper, capsules and metal for sparkling wine cages, which suddenly became difficult to find products, and prices at least doubled.

How has climate change impacted Emilia-Romagna?

This is a very important topic. The climate has changed a lot here. The harvests happen one month earlier than 20 years ago. And, if this may not seem to be a negative variation, the dramatic facts are that the spring frosts, the much more frequent summer hails (in 2019, 10 hectares of vineyards were totally destroyed) and the great drought that is now constant in the months of July and August most certainly are. My belief in producing little to make better starts to fail. Too much concentration seems to lead to a loss in balance. I realized that the newest vineyards I planted lately with the goal to produce a little more have more vigorous vines with greater leaf coverage that better resist drought and keep the bunch in the shade rather than sun baked. The climate changes and viticulture has to adapt to these changes.

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las

Vegas

Eating Las

Vegas

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher

Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish.

Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2022