MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

August 14, 2022

NEWSLETTER

IN THIS ISSUE

THE

ENDURING IDIOCY OF

GROVELING FOR AN

“A” TABLE

NEW YORK CORNER

HARRY'S TABLE BY CIPRIANI

By John Mariani

ANOTHER VERMEER

CHAPTER 33

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

CHABLIS: A GOOD BISTRO WINE

BUT AN EXCELLENT BURGUNDY, TOO

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

❖❖❖

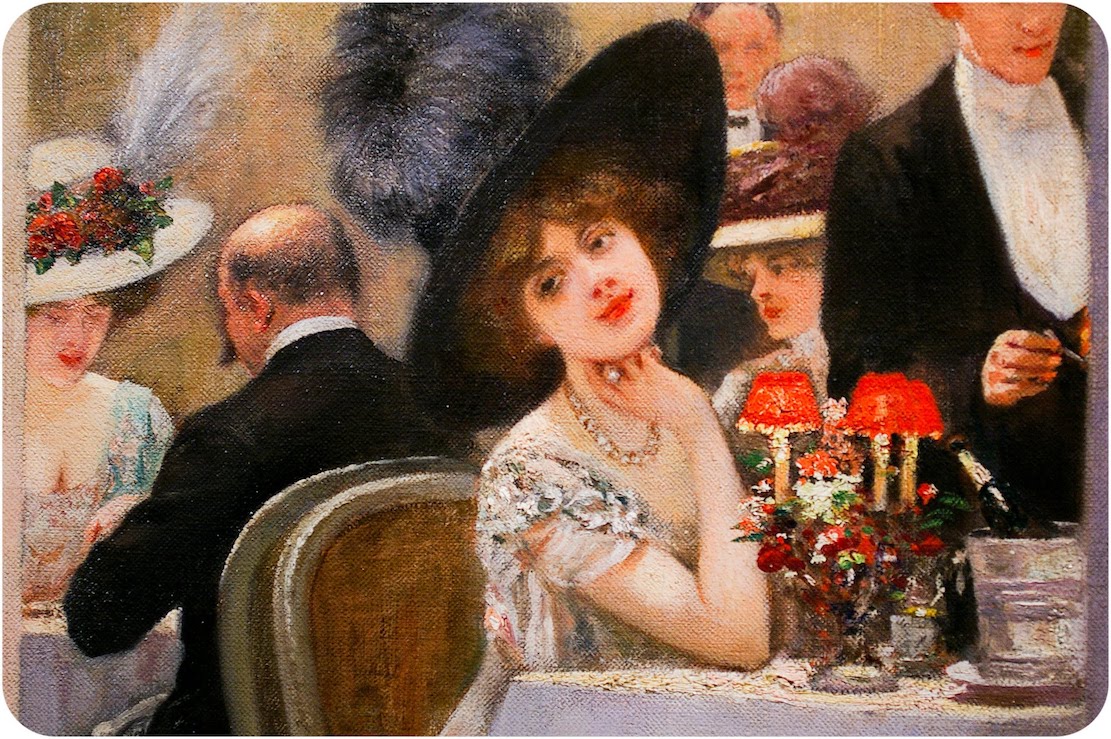

THE

ENDURING IDIOCY OF

GROVELING FOR AN “A” TABLE

LE CIRQUE, NYC, 1998

At a time when some of the toughest

reservations to get are at storefront eateries

in Brooklyn with long communal

tables, the outdated idea that restaurateurs

deliberately design their dining

rooms to have “good” and “bad” tables is as

preposterous as deliberately

writing a novel with good and bad chapters. As

every restaurateur will tell

you, theirs is a business that depends on the

total utilization of every square

foot of a room to maximize occupancy, while

allowing for flow, décor and the

ability of the kitchen to deliver a certain

amount of food per hour.

Yes, there

once really was such a thing

as “Siberia,” a term for a section

of a

restaurant dining room considered either socially

inferior or merely poor

seating that was coined back in the 1930s when

society woman Peggy Hopkins

Joyce (left) entered the class-conscious El

Morocco nightclub in New York and found

herself being led to a less than desirable table.

“Where are you taking me,”

she asked the maître d’hôtel, “Siberia?” An

alternate term for Siberia is the

“doghouse,” used by those who frequented

Yes, there

once really was such a thing

as “Siberia,” a term for a section

of a

restaurant dining room considered either socially

inferior or merely poor

seating that was coined back in the 1930s when

society woman Peggy Hopkins

Joyce (left) entered the class-conscious El

Morocco nightclub in New York and found

herself being led to a less than desirable table.

“Where are you taking me,”

she asked the maître d’hôtel, “Siberia?” An

alternate term for Siberia is the

“doghouse,” used by those who frequented  New York City’s Colony

Restaurant,

opened in 1926. An “A” table was one supposedly

given to VIPs that was usually

at a banquette against the wall in full view of

everyone on their way to a

lesser table.

New York City’s Colony

Restaurant,

opened in 1926. An “A” table was one supposedly

given to VIPs that was usually

at a banquette against the wall in full view of

everyone on their way to a

lesser table.

It hardly mattered to such people that the

food and drinks were going to be the same,

although some fools would argue that

a restaurant would have different cooks for

different guests and the chef would

tell his cook that he should make great food for

Table 4 but not to bother with

Table 18, which is a screwy and impossible way to

run a kitchen. A chef doesn’t

keep two pots of goulash on his stove in case Brad

Pitt or a restaurant critic

shows up.

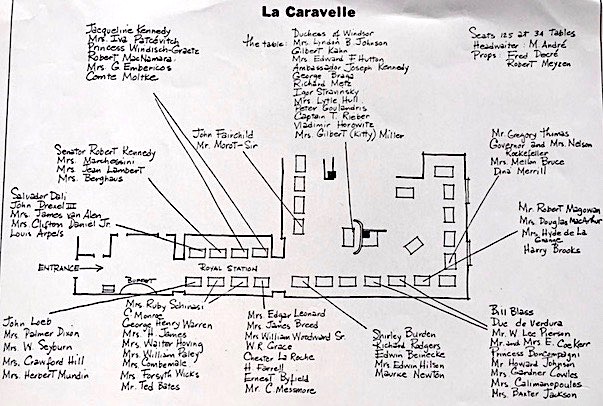

To be sure, in the days of New York's El

Morocco (right), The

Colony and `21” Club, all now defunct, arrant

snobbism did rule—the doorman at

`21’ was once quoted as saying, “Why should I be

nice to everyone? I don’t know

them.” And

I’m well aware that many, if

not most, restaurants have tables that might be

perceived as particularly

pleasant and that faithful, six-times-a-month

customers and, yes, celebrities,

are given those nicer tables, which seems to me to

be good business in the case

of the faithful regulars and obviously worthwhile

in the case of celebs. If you’ve

frequented a restaurant for years, you, too, will

be one of those favored.

But in so many

cases it is a person’s perception

about the value of a table

that creates trouble. The most notorious example

was when the newly arrived

(from L.A.) New

York Times restaurant

critic Ruth Reichl (left) in the 1990s

wrote a double review of what was then the

city’s most celebrated restaurant, as much for its

food as for its

international clientele and suave owner, Sirio

Maccioni (below), whom Reichl considered

“the most fabulous looking guy you ever saw in

your life.” After eating at the

restaurant six times (the Times

gave

their critics complete carte blanche with

expenses), Reichl contended that when

she was unknown she was given a bad table, endured

rude

But in so many

cases it is a person’s perception

about the value of a table

that creates trouble. The most notorious example

was when the newly arrived

(from L.A.) New

York Times restaurant

critic Ruth Reichl (left) in the 1990s

wrote a double review of what was then the

city’s most celebrated restaurant, as much for its

food as for its

international clientele and suave owner, Sirio

Maccioni (below), whom Reichl considered

“the most fabulous looking guy you ever saw in

your life.” After eating at the

restaurant six times (the Times

gave

their critics complete carte blanche with

expenses), Reichl contended that when

she was unknown she was given a bad table, endured

rude service and ate “a

parade of brown food.” But, she contended, when

“discovered” by Maccioni, she

caved into his considerable charm and had a great

meal. (Four years later she

awarded Le Cirque the top rating of four stars.)

service and ate “a

parade of brown food.” But, she contended, when

“discovered” by Maccioni, she

caved into his considerable charm and had a great

meal. (Four years later she

awarded Le Cirque the top rating of four stars.)

It should be noted that Reichl was easily

recognized all over town because she is a very

distinctive looking woman with

glasses and a mass of curly black hair that she

sometimes covered with a wig,

something no male or female restaurant critic for

the Times had ever done before.

Reichl was not the first to have

complained of a two-tier system of preference at

Le Cirque, but, despite her

insistence that she was undiscovered until that

last meal, Maccioni said she’d

been known from her first visit but they did not

fawn over her, lest they give

the game away. It also never occurred to her that

eating at Le Cirque six times

in a short period might have made her a treasured

regular.  As for the “brown

food” at the start, well, those are dishes she

ordered; when the food got

better, were they the same dishes but no longer

brown?

As for the “brown

food” at the start, well, those are dishes she

ordered; when the food got

better, were they the same dishes but no longer

brown?

Moreover, years later Reichl complained

she was given a terrible table just inside the

entrance of a re-located Le

Cirque, but in fact that was the same table

where

Sophia Loren (left) had been seated the

night before and one favored by many

other celebrities. Such carping has died down in

this present century (and Le

Cirque is closed), and as Maccioni used to say,

“The table does not make the

person; the person makes the table.”

The issue of perception continues,

however, with people who as first-timers find

themselves seated at a perfectly

nice table that they believe is punishment for

their lowly status. Given the

obvious fact that in a dining room of, say, 30

tables, 25 of them are going to

be placed all over the room, with perhaps five up

front or against a window or

banquette. As noted, restaurants are real estate,

but, unlike theaters, arenas

and airlines, restaurants cannot charge extra for

front row seats or

first-class, fully reclining seats.

Which

leads to the heinous practice of

people bribing the maître d’ at a restaurant.

While requisite in season at

Joe’s Stone Crab on .jpeg) Miami

Beach, whose oily maître d’ (right) was

once said to wield more

power than the city’s mayor, payment for a table

marks the average person as a

patsy who will thereafter always be a mark for the

staff. It goes without

saying that former plumbing contractor John Gotti

(below)got preferential treatment at

restaurants because he always tipped the staff the

entire amount of the bill.

Later, of course, he was taking his meals through

a slot in solitary

confinement at Chez Marion Penitentiary.

Miami

Beach, whose oily maître d’ (right) was

once said to wield more

power than the city’s mayor, payment for a table

marks the average person as a

patsy who will thereafter always be a mark for the

staff. It goes without

saying that former plumbing contractor John Gotti

(below)got preferential treatment at

restaurants because he always tipped the staff the

entire amount of the bill.

Later, of course, he was taking his meals through

a slot in solitary

confinement at Chez Marion Penitentiary.

If,

in fact, one does intend to become a regular at a

chosen restaurant, there’s

nothing wrong with making that clear to a maître

d’ and tipping him upon

leaving. He will remember. But to say that only

such payments guarantee good

service and a preferred table is not to understand

how restaurant seating is

arranged on an every night basis.

If,

in fact, one does intend to become a regular at a

chosen restaurant, there’s

nothing wrong with making that clear to a maître

d’ and tipping him upon

leaving. He will remember. But to say that only

such payments guarantee good

service and a preferred table is not to understand

how restaurant seating is

arranged on an every night basis.

Considerations of traffic flow are as

important as knowing how many tables can be

accommodated when the six o’clock

rush begins. Dining rooms have sections assigned

to captains and waiters each

night, and that will change each night. Staff

would grumble otherwise. Thus,

guests must be placed in each and all of those

sections.

Be aware, too, that tips to captains,

waiters, busboys and bartenders are always shared

at the end of the night and,

by law, whatever percentages they decide on cannot

be interfered with. Thus, a

good waiter will get the same amount as a bad

waiter, although the good waiters

will make sure the bad ones don’t stay long in

their jobs. So, to suggest that

a parade of nightly regulars and celebs will only

get the best waiters at the tables

perceived to be the best is simply not in accord with

the way things run in a

restaurant.

But, what if you are interested in

getting

a “good” table and good service (assuming the

restaurant doesn’t have special

cooks who only cook good food for special people)?

The answer is very simple:

Just ask. Very often upon arrival I have asked to

change tables because the one

over there is empty or the one over there is in a

quieter section. Almost

always (I’m speaking of places I’m not known), my

request is cordially granted.

I am not going to ask for a table I can clearly

see has a “RESERVED” sign on

it.

But, what if you are interested in

getting

a “good” table and good service (assuming the

restaurant doesn’t have special

cooks who only cook good food for special people)?

The answer is very simple:

Just ask. Very often upon arrival I have asked to

change tables because the one

over there is empty or the one over there is in a

quieter section. Almost

always (I’m speaking of places I’m not known), my

request is cordially granted.

I am not going to ask for a table I can clearly

see has a “RESERVED” sign on

it.

It’s certainly not a bad idea, when

possible, to drop by the restaurant earlier and

see what the lay-out and the

prospects will be for dining there that night—and

remember, everything is

easier at lunch. Or call ahead and tell the maître

d—not the person who answers the

phone!—about your preferences: This

will be a business meal where you need some quiet

reserve; or a romantic

dinner, perhaps a celebratory anniversary or

birthday; or a meal with an

elderly person who may need some help getting in

and out.

Remember,

restaurants are service

businesses; they are not in the business of

shunning, ridiculing or losing

customers unless they are rude and boisterous.

Restaurateurs work very hard to

win your business and they can only do that by

winning you over. Let them do so

in their own cordial way. Or you could always try

to get a reservation at that

communal table at the storefront in Brooklyn. Good

luck with that.

❖❖❖

HARRY’S TABLE BY CIPRIANI

235

Freedom Plaza South, at Waterline Square

212-339-2015

By John Mariani

New

Yorkers

have never wanted for Italian specialties shops,

but New Yorkers have

never seen anything quite like the new Harry’s

Table by Cipriani (hereafter

HTC), outside of the stunning, long-lived PECK in

Milan, and far more appealing

than the touristy New York EATALY stores. In its

breadth of space alone—28,000

square feet—HTC sets an unhurried pace, and, while

sometime in the future it

may be jammed, for the moment the eight-week-old

market is a civilized pleasure

to visit, shop in and eat at.

HTC

is located at ground level in the dwarfing,

monolithic Two Waterline

Square, near Lincoln Center, from which it currently

draws most of its

clientele. Since parking (outside of an expensive

lot) is almost impossible,

dropping by for those who do not live in the area

will require you take a taxi

or car service.

HTC

is located at ground level in the dwarfing,

monolithic Two Waterline

Square, near Lincoln Center, from which it currently

draws most of its

clientele. Since parking (outside of an expensive

lot) is almost impossible,

dropping by for those who do not live in the area

will require you take a taxi

or car service.

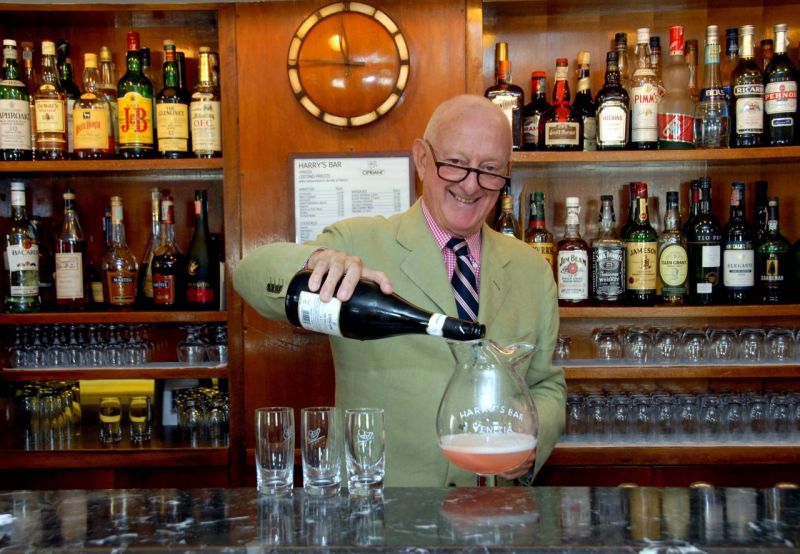

The sprawling food market is the first by the

Cipriani family, whose

legendary history dates back to 1931, when bartender

Giuseppe Cipriani opened

his Harry’s Bar in Venice on the first floor of an

abandoned warehouse on a

dead-end street off the Piazza San Marco. Small and

decidedly low-key in its

décor,

Harry’s Bar drew an international crowd, including

Americans who, until

1933, couldn’t get a drink in their own country.

décor,

Harry’s Bar drew an international crowd, including

Americans who, until

1933, couldn’t get a drink in their own country.

Commandeered as a Fascist canteen during the

war, Harry’s would re-open

to even greater acclaim and a celebrity guest list

that included Orson Welles,

Ernest Hemingway and most potentates of Europe, all

the while serving a small

menu of what became Cipriani classics, like the bellini cocktail, carpaccio,

tagliatelle

alla gratinate and risotto

with seppie.

Giuseppe and his son, Arrigo (right) ,

refused ever to open another restaurant

using the name Harry’s, but as of the 1980s,

Arrigo’s son did open restaurants

and function spaces under various Cipriani-related

names in New York, Miami,

Los Angeles, Abu Dhabi, Hong Kong, Monte Carlo,

Ibiza, Mexico City, Dubai,

Riyadh and Las Vegas, with more in the works. It is

the fourth generation of

Ciprianis, Maggio and Ignazio, that is now

overseeing HTC.

The sleek, airy space was designed by

London-based AD100 interior designer Martin

Brudnizki,

done in terrazzo, subway tiles, brass, natural wood,

globe chandeliers and blue

and orange colors, said to be inspired by a

traditional Italian street filled

with local vendors, such as a butcher and cheese

monger—though I know of no

street in Italy that remotely has the New York swank

of HTC.

As you enter you see a long receding space

that curves around to the

Bellini restaurant in the rear, with a splendid

outdoor piazza set with tables

and ringed with lights facing the Hudson River. Up

front you’ll smell the

Lavazza Italian coffee being brewed and

out-of-the-oven pastries available as

of 7a.m. Then there is a gelateria

and pasticceria, where

you’ll find the renowned vanilla

meringue and lemon pie that are served in all

Cipriani restaurants. As you move

along you find a juice bar (which seems a tad out of

character for an Italian

food shop), then a place for signature salads.

As you enter you see a long receding space

that curves around to the

Bellini restaurant in the rear, with a splendid

outdoor piazza set with tables

and ringed with lights facing the Hudson River. Up

front you’ll smell the

Lavazza Italian coffee being brewed and

out-of-the-oven pastries available as

of 7a.m. Then there is a gelateria

and pasticceria, where

you’ll find the renowned vanilla

meringue and lemon pie that are served in all

Cipriani restaurants. As you move

along you find a juice bar (which seems a tad out of

character for an Italian

food shop), then a place for signature salads.

Fresh

pasta, such as ravioli and

tagliatelle, can be purchased

uncooked, or made to order for

take-out or eat-in, along with a “Gastronomia” of Italian

dishes like the Venetian baccalà

montecato, artichokes alla Romana

and lasagna alla bolognese.

By

this time you are only hallway around: next is the

stop for panini

sandwiches, including the

Venetian soft sandwiches called tramezzini.

The bread selections are impressive. Then you come

to the pescheria, stocked with a variety of

seafood (though the offerings

should be topped

with crushed ice,

not just sit on it). Carne comes

from

the on-premises New England-based Fossil Farms

Artisan Butcher offering an

impressive array of beef, lamb and pork, grass-fed,

as in Italy, although

corn-fed American beef has much more marbling.

Of course, there’s pizza (below) in

multiple variations, and then an

extraordinarily beautiful case of cheeses, most

Italian, and salumi. The

Ciprianis have always had a caviar clientele, so

they have a caviar and smoked

salmon section from Caviarteria, although, by

international law, Russian and

Iranian Caspian Sea caviar is banned from sale. Here

the offerings are all farm

raised elsewhere.

If you’ve come by to shop, you can also eat

at casual tables at HTC,

with the food brought to you if you like, including,

perhaps, a crudo

tasting. A

bright, glistening bar that evokes the

original Harry’s Bar is a fine spot for a bellini

or other cocktail or glass of wine before heading

home or to Lincoln Center.

If I lived in this Upper West Side

neighborhood, I might still go

occasionally to the local warehouse-like Whole Foods

or Fairway for non-Italian

products, and I might go to Citarella for something

special. But  I

suspect I

might spend a good deal of time and money at HTC,

starting off with a

cappuccino and brioche in the morning, meeting a

friend for lunch, or cocktails

at six, and, if so inclined, to pick up some bread

and charcuterie, maybe a

little cheese, and, why not get a pizza, bring back

some pasta, and for a treat

a pint of gelato?

I

suspect I

might spend a good deal of time and money at HTC,

starting off with a

cappuccino and brioche in the morning, meeting a

friend for lunch, or cocktails

at six, and, if so inclined, to pick up some bread

and charcuterie, maybe a

little cheese, and, why not get a pizza, bring back

some pasta, and for a treat

a pint of gelato?

Had HTC had only these products, it would be

easy enough to do. But it’s

also such a beautiful space to linger in, I suspect

this would become my

neighborhood bar, grocery and place to get a bite of

this or that or that or

that, too. Since I do not live in

the

neighborhood, if I could find a parking space, I’d

go there for all the same

reasons.

Open

daily; Caffe 7 a.m.-9 p.m.; Market 11 a.m.-9

p.m.

❖❖❖

ANOTHER VERMEER

By John Mariani

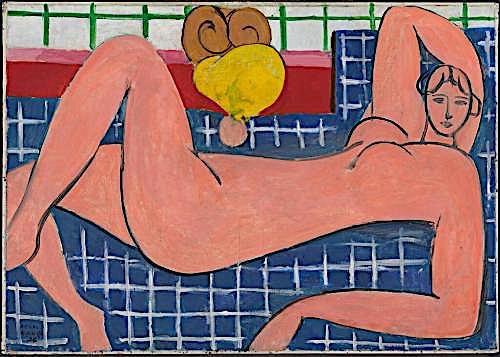

ART TODAY

Matisse

Reclining

Nude Sells for Record $9.2 Million

An

Interview

with Taiwan Collector Hai Shui

`````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````

Art Today

came out

on Wednesday with a profile of Hai Shui, and

while it stated that the

billionaire was considered a very tough

businessman by many critics, the

article did not expose anything truly

nefarious about him. It did note that the

Shui family had been one of those to get gold

and artwork out of China during

the revolution and that much, if not most, of

it was in his private collection.

The article confirmed that Shui had not

donated much to Taiwan institutions.

Katie had expected such an article, after

hearing that Shui

had flown Coleman over and wined and dined him

in Taipei. So she pretty much

decided not to share information with her old

friend, who called her that day.

“What, you’re not speaking to me, Katie?”

asked Coleman.

“Not at all, but I just think we should

follow our own

investigations separately on the Vermeer

auction.”

“Gee, and I was just about to tell you

the news.”

Katie forced herself to be silent, then

said, “It’s up to

you if you want to tell me.”

“Well, it’s nothing everyone won’t read

next Wednesday

anyway. I’ve got the time and place of the

auction. It’s going to be November

25th, three days before Thanksgiving, which of

course they don’t celebrate over

there.”

“Okay,” said Katie, stifling any emotion.

“And the auction house is named

Crofthouse, in Hong Kong. A

small but well-regarded house long owned by the

Brits. Quite a coup for them.”

Katie was writing the information down

and said, “Well,

thanks, John. You’re a good guy. Just try to

understand where I’m coming from

with this.”

“I do, Katie, but cut me some slack here,

will you. I do the

best I can with the little I’m given, and Shui

handed me a plum.”

“We all gotta do what we gotta do,” she

said. “And

when this is all over, I’ll buy you

dinner. How’s that?”

“I’ll look forward to it, Katie. Maybe a

good Chinese

restaurant. And good luck with your research.”

Katie

resigned herself to keeping on her track without

Coleman’s help, but as he himself said, she was

only getting advance notice of

info that would most likely be in the upcoming

issues of Art Today. And for her part she

really hadn’t given Coleman much of

anything useful for weeks.

Katie

resigned herself to keeping on her track without

Coleman’s help, but as he himself said, she was

only getting advance notice of

info that would most likely be in the upcoming

issues of Art Today. And for her part she

really hadn’t given Coleman much of

anything useful for weeks.

She phoned David and told him the news,

saying she’d put in

the appropriate calls to Crofthouse for their

official comment, then called Sotheby’s

and Christie’s to get theirs. As expected,

Sotheby’s and Christie’s had no

comment beyond wishing Crofthouse good luck with

the sale, so she called Kevin

O’Keeffe at the Mannion Gallery in New York, and

asked his response.

“Off the record?” asked O’Keeffe.

“You mean not for attribution?”

“Right, I don’t want to be named.”

“Okay, shoot.”

“This all seems very, very strange, but

in a way I

understand why the Chinese are choosing

Crofthouse. First, it’s located right

there in Hong Kong.”

“But don’t Sotheby’s and Christie’s have

offices there?”

“Yeah, Sotheby’s been there since the

seventies, Christie’s

since the eighties. Both sell primarily Asian

art. Crofthouse goes way back as

a British house, opening, I think, in the

fifties, so they’ve got a lot of

clout in that region and all the necessary

contacts and connections with the

mainland Chinese. Now that the Chinese regained

sovereignty over Hong Kong in '97, Crofthouse

would be a natural choice.

“But there’s another reason I think they

chose Crofthouse:

The painting has to be vetted, and I’m sure

Sotheby’s and Christie’s would

demand a much more vigorous investigation into

provenance and authenticity,

which, as you know, with that other supposed

Vermeer in the market, could take

a very long time. Something tells me Crofthouse

is willing to be a little less

demanding in that regard, probably arranging for

a few Vermeer scholars to take

a close look at the painting, maybe allow an

x-ray, but then put the piece up

for sale as scheduled. It would be a huge public

relations coup for

Crofthouse—which also stands to make at least

$10 million off the sale—and make

them the conduit for any sales the Chinese

arrange in the future. Asia is

becoming a very big market for art.”

“And, if it turns out to be a fake?”

asked Katie.

“Crofthouse won’t look so good, but with

the backing of the

experts and the Chinese government, I don’t

think they’re risking being

sued. Also,

authenticity is warranted

for only five years, and if the buyer cries foul

a year after the auction, the

burden of proof is on him, not the auction

house. It’s

tricky these days but this is China, not

Europe or the U.S.”

Katie asked, “Do you have a name I could

call at

Crofthouse?”

“Matter of fact, I know one of the

principals quite well. We

buy from and sell to each other. Name is Derrick

Donaldson, good man.”

“You think he’ll talk to me?”

“I’m happy to give him a call in

advance,” said O’Keeffe.

“I’ll let you know tomorrow.”

Now on this new trail, Katie also called

Prof. Elizabeth

Horner at Fordham, asking if she knew who the

Vermeer scholars were who were

going for the inspection. Horner gave her three

names, Andrea Kenner at the Rijksmuseum in

Amsterdam, Jacob Strohe at the Kunstmuseum (right)

in

Vienna and Marie-Céline Bourget at the Louvre in

Paris.

“And you think their reputations are

solid enough that

they’ll give their honest opinion?” asked Katie.

“They’ll be paid a great deal of money,

I’m sure,” replied

Horner. “That can sway a person, but they are

first-rate scholars, and if

there’s something readily suspicious about the

painting, they’ll certainly

report it.

Three pairs of eyes and

magnifying glasses are going to go over every

inch of that painting.”

It wasn’t easy getting to the experts.

Two of them, Strohe

and Bourget, had already left for Hong Kong.

Kenner was due to leave soon, and

Katie was able to reach her at her office in the

Rijksmuseum (below).

After the expected demurral about not

being able to say

anything authoritative until she saw the

painting, Kenner said she believed it

might very well be a Vermeer, based on the

photographs she’d seen.

“If it’s not a Vermeer,” she said, “it

looks to be an impeccable forgery.

The fact that it seems to be a third in a series

of scientists is interesting,

too, at a time when interest in science was

growing very rapidly in Holland.”

Katie

thought for a moment whether to tell Kenner

about the

alchemy reference, then did so, believing the

more Katie sounded like she knew

what she was talking about the more likely

Kenner would be to speak.

Katie

thought for a moment whether to tell Kenner

about the

alchemy reference, then did so, believing the

more Katie sounded like she knew

what she was talking about the more likely

Kenner would be to speak.

“Ah, yes,” said Kenner, “that was very

obvious from the

tools and beakers in the painting, which should

more properly be called The

Alchemist. And there might be some

symbolic reference in the fact that the globe—we

know where it came from—is

deliberately turned towards China, but it’s not

clear to me why.”

Katie decided it would sound too

conjectural to get into the

supposed connection to China’s seeking gold from

the West or about the Shui

family. She

thanked Kenner and asked if

she might check with her as her investigations

went along.

“I’m afraid none of us can speak to

anyone about that until

we release our official findings.”

A day later Katie was able to speak with

Jacob Strohe, who

said the same thing about the ongoing work.

“I have spent an hour or so with the

painting,” he said,

“and I can only say I am impressed with what

I’ve seen. But that is a very

preliminary opinion. We are also waiting for the

results of an x-ray, which

will tell us more.”

It took two more days to reach

Marie-Céline Bourget, who

refused any comment whatever beyond saying that

the painting was in fairly good

condition and that her work, along with Kenner

and Strohe, was made easier by

not having to imagine what was under layers of

dirt and varnish.

“Is there anything about the painting

that you think may be

a problem?” asked Katie.

“Nothing obvious right now,” Bourget said

in Oxford-accented

English with a French lilt. “I am a little

suspicious about the way the artist

rendered the right sleeve of the figure, which

doesn’t match the refinement

seen in the other two scientist paintings. You

know, we have The

Astronomer at the Louvre, so I am

very intimately familiar with that work.

But not much else is troubling me right

now.”

© John Mariani, 2016

❖❖❖

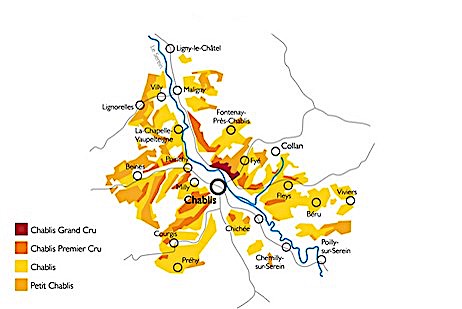

CHABLIS: A GOOD BISTRO WINE

BUT AN EXCELLENT BURGUNDY, TOO

By John Mariani

What’s in a name? In the case of Chablis,

far more than the producers of this white Burgundy

wine would like to hear. For

“chablis” is one of those wine names that has

acquired a freewheeling, generic

usage in the market. Many countries, including the

U.S., appropriate the name

without any relevance to the true Chablis.

American wine giant Gallo even makes

a Blush Chablis under its Livingston label.

True

Chablis, which takes its name from a

town of that name, can be a superb white wine, made

exclusively from Chardonnay

grapes, although it rarely reaches the level of more

prestigious white

burgundies made to the south in the Côte de Beaune.

Chablis is made under

strict French wine regulations that designate the

region’s vineyards. The best

of these are the 7 Grand Crus and the 17 Premier

Crus.

True

Chablis, which takes its name from a

town of that name, can be a superb white wine, made

exclusively from Chardonnay

grapes, although it rarely reaches the level of more

prestigious white

burgundies made to the south in the Côte de Beaune.

Chablis is made under

strict French wine regulations that designate the

region’s vineyards. The best

of these are the 7 Grand Crus and the 17 Premier

Crus.

About 32

million bottles of Chablis are

made each year from vineyards comprising 4,300

hectares (10,500 acres) in 20

villages. About a third of that is vinified by the

cooperative La Chablisienne,

but more and more individual proprietors are now

bottling their own Chablis,

leading to different styles of the wine.

Two centuries ago Chablis was vastly

successful as a cheap white wine easily shipped to

nearby Paris. When railroads

proliferated in France the mid-19th century, wines

shipped from regions farther

away challenged Chablis’ dominance of the market.

Still, Chablis endures as the

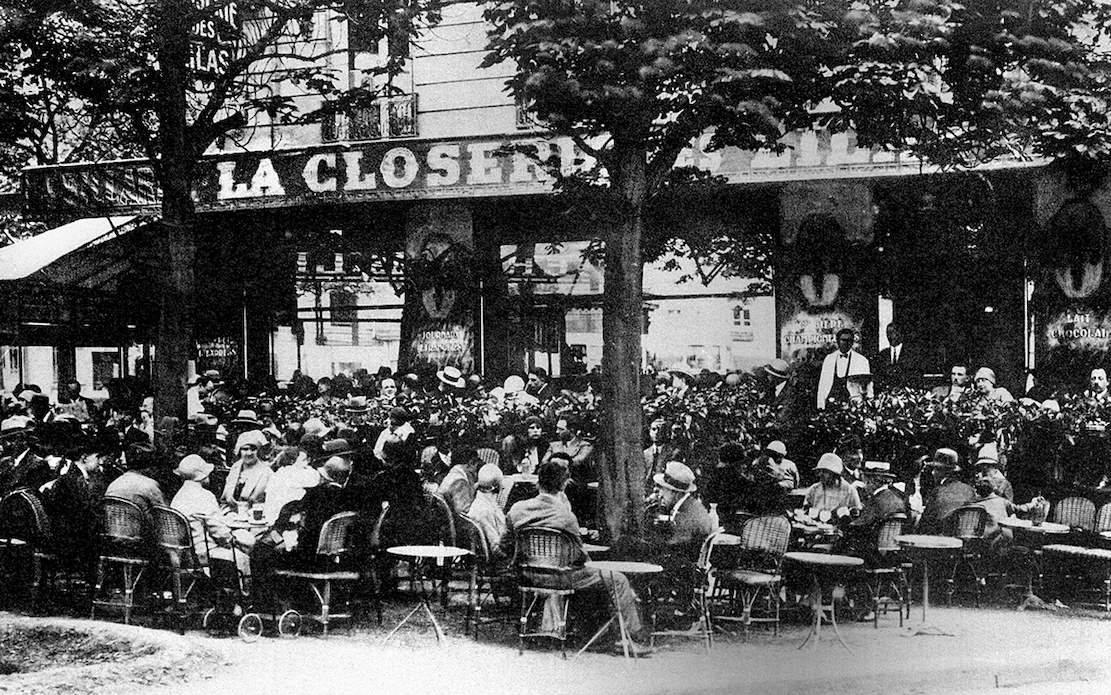

steely, mineral-rich wine traditionally quaffed with

oysters and shellfish in

Parisian bistros like La Rotonde, La Coupole, and

Closerie des Lilas.

The identifying mineral character of

Chablis comes from soil rich in limestone, clay, and

fossilized oyster shells.

There has been a debate in recent years among

producers as to whether Chablis

should be aged in oak barrels. Many producers

believe Chablis retains its

distinctive “gunflint” (“pierre à fusil”)

flavor

better in the sterile atmosphere of stainless steel;

others,

particularly among the Grand Cru and Premier Cru

producers, say a few months in

oak imparts more character to Chablis.

What I love about good Chablis is its

distinctive quality and its lack of pretension. It

should be drunk cold, in or

out of doors, and goes as well with lunch as with

dinner, with fish as well as

chicken. In The

Sun Also Rises Ernest

Hemingway wrote of his characters drinking Chablis

with sandwiches while on the

train from Paris to Spain, noting, “The grain was

just beginning to ripen and

the fields were full of poppies.”

Perhaps more important

to Chablis’

character is the time it takes to mature in the

bottle. Unlike most white wines

in the world, including California Chardonnays,

Grand and Prémier Cru Chablis

may not reach their peak for seven to fifteen years,

the same as big name

burgundies like Meursault and Corton-Charlemagne.

Over time, Chablis’ flavors

deepen, the minerals and acids come into balance and

the bouquet develops. For

this reason the better Chablis are not released for

two or more years. Right

now wine from the highly regarded 2020 vintage is

available at wine shops.

La Chablisienne Premier Cru 2020 ($30)—A classic effort from Vaillon, well made, flinty but with good fruit, ideal with chilled fresh oysters, or mussels with a touch of mayonnaise.

Jean-Paul & Benoit Droin’s Premier Cru 2020 ($30)—Chablis from the Montmains vineyard has always shown a perky acidity, with the nose tight, the minerals in modest evidence, all of which should come into balance in a year or two. The producer has yet to release its 2020 Grand Cru.

Jean-Marie Brocard’s Premier Cru Montmains 2020 ($35)—Shows some real finesse and complexity, but this is one I want to hold onto because a few years from now it should really be magnificent.

Domaine William Fevre 2020 ($55)—From Bougros, with lots of mineral notes both in the nose and the taste. First came an acidic rush, then vibrant tingles of that gunflint flavor that distinguishes Chablis from the rest of Burgundy’s wines. Its Premier Cru costs about double.

There is still a lot of cheap, inferior Chablis from France on the market, so if you like the taste of the wine, it’s better to buy from the Grand Cru and Premier Cru categories, even if you have to wait a while for them to reach their peak.

Below the Grand Cru and Premier Cru categories (which themselves may be de-classified if the wine doesn’t meet quality standards) bottles are labeled just Chablis, with no vineyard names attached (there is also an even lower category called Petit Chablis). So, more or less, you get what you pay for, and that should not be upwards of $15. If you do buy one of those, maybe pour it into a carafe and serve it up with oysters and charcuterie, the way they do at a Paris bistro. At least it will be authentic.

❖❖❖

WHICH BEGS THE QUESTION, WHAT THE HELL

WERE THEY PUTTING IN THEM BEFORE?

"It’s

Time to Put Actual Veggies Back

Into Veggie Burgers" by Jaya Saxena, Eater.com

(7/15/22)

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

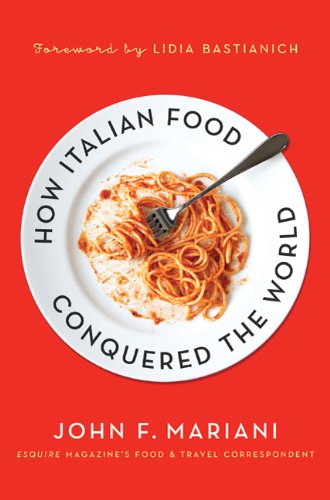

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las

Vegas

Eating Las

Vegas

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher

Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish.

Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2022