MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

October 30, 2022

NEWSLETTER

Founded in 1996

ARCHIVE

Judy Garland in Halloween

IN THIS ISSUE

YALE STUDENTS ENJOY THE BEST

FOOD OF THEIR YOUNG LIVES

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

MICHAEL'S NEW YORK

By John Mariani

ANOTHER VERMEER

CHAPTER FORTY-THREE

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

CLIMATE CHANGE IS AFFECTING WINERIES

SOONER RATHER THAN LATER

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

Dean Defino on the Relevancy

of the Cinema Canon. Go to: WVOX.com.

The episode will also be archived at: almostgolden.

Dean Defino on the Relevancy

of the Cinema Canon. Go to: WVOX.com.

The episode will also be archived at: almostgolden.❖❖❖

YALE STUDENTS ENJOY THE BEST

FOOD OF THEIR YOUNG LIVES

By John Mariani

I’ve never met anyone over the age of thirty who has fond memories of school cafeteria food, except my wife, who grew up in Paris, where a school lunch was three courses, including cheese. Indeed, school food usually compares with airline and hospital food, and in primary and secondary schools mandated healthy food options are usually trashed by students consuming chicken fingers and burgers on a daily basis.

On the college level, however, I have

noticed significant changes. Under

student persuasion, food service has generally

improved—every college now seems to serve sushi at

least once a week and vegetarian options are now a

given. But I was not prepared for the breadth, depth

and high quality of the food service at Yale

University, where a $7,000 food plan is included in

the $80,000 tuition.

On the college level, however, I have

noticed significant changes. Under

student persuasion, food service has generally

improved—every college now seems to serve sushi at

least once a week and vegetarian options are now a

given. But I was not prepared for the breadth, depth

and high quality of the food service at Yale

University, where a $7,000 food plan is included in

the $80,000 tuition.On my visit to New Haven my tour took me into the two new colleges (which are dormitories) of Franklin and Berkeley, where three meals a day are offered. By 12:25 these beautiful new dining halls, done in the Oxford-inspired neo-Gothic architecture of the rest of the school, are thronged with ravenous students whose options range from house-made bread, sandwiches, soups, salads and pasta to desserts.

There are even two pizza options derived from the New Haven styles featured at Frank Pepe’s and Sally’s Apizza. There is even a kosher kitchen at the Slifka Center for Jewish Life (right).

As much as possible the food served is based on as much local product as possible, and in 2020 a survey of students showed that they wanted a better understanding of carbon emissions associated with food intake, with 86 percent of respondents in favor of posted environmental impact ratings. (A minority said they were offended by the poster because the ratings wrongfully made them feel guilty about their dining choices.)

At all the colleges students dine with teachers, and, if you are invited in by either, the public can, too; at the largest, oldest dining hall, called the Schwarzman Center, anyone can walk into the Commons and pay for a meal, which includes Persian-spiced rotisserie chicken, saffron butter fingerling potatoes, roasted tomato

with

feta, pork

with black bean sauce, spicy noodle salad, wok-fired

dishes, Chinese dumplings and warm chocolate chunk

cookies.

with

feta, pork

with black bean sauce, spicy noodle salad, wok-fired

dishes, Chinese dumplings and warm chocolate chunk

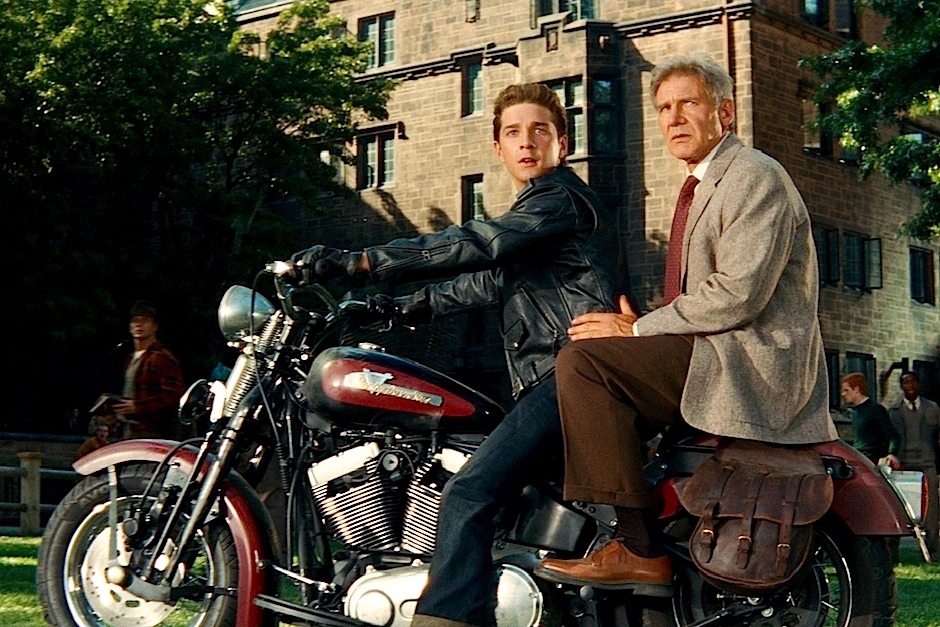

cookies.So large and grand is the Center’s dining hall that Stephen Spielberg took it over for weeks in 2007 to film a scene in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, wherein a character escapes through it on a motorcycle.

Within the Center, there is a pay-as-you-go room not on the meal plan where fresh gelato, pastries and espresso can be enjoyed before a fireplace and farther on The Ivy is a late-night venue where students with the munchies can order tacos, sliders, Ghanian beef chili and sushi rolls. Then there is The Well, a pub (you need to be 21 to drink in Connecticut) for beer and wine and tidbits of Wok-Fired Peanuts with Thai Chili, Lemon & Basil Salt, Truffle Grilled Cheese on Rye, even a Cheese & Charcuterie Platter.

The Center is named after Yale grad Stephen Schwarzman, CEO of The Blackstone Group, who gave the university $150 million for food service facilities.

Serving 15,000 meals a day is a daunting process, overseen by a staff of 800 within the Yale Hospitality group, which supports over 14 residential dining halls, 13 restaurants and cafes and extensive catering facilities. (No students are employed by Yale Hospitality.) Without being doctrinaire about it, their intent, according to Associate Vice President Rafi Taherian, is to make “good for people and good for the planet.” Hamburgers are only occasionally on menus, though the excellent fried chicken is one of the best sellers each day.

Working closely with the

Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, NY, and

Johnson & Wales in Providence, RI, the company

brings in celebrated chefs to share their expertise

with the culinary team, and has collaborated on

“Ingredients for a Sustainable World: The Chef’s

Good Food Handbook” and the 2019 Food Forward Forum

with the Good Food Fund in China and partnering with

the Mediterranean diet round table to create

plant-forward menus.

Working closely with the

Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, NY, and

Johnson & Wales in Providence, RI, the company

brings in celebrated chefs to share their expertise

with the culinary team, and has collaborated on

“Ingredients for a Sustainable World: The Chef’s

Good Food Handbook” and the 2019 Food Forward Forum

with the Good Food Fund in China and partnering with

the Mediterranean diet round table to create

plant-forward menus. During the pandemic, with Yale closed, the group had to shut down its catering department but retained all employees, who were kept busy with developing new approaches, economies and menus.

That all this costs a fortune for a non-profit-making organization has not been a problem, since Yale, with a $41.4 billion endowment, can well afford to subsidize food service and do so with a commitment to variety, quality, sustainability and service.

One would think that’s a reasonable expectation for an $80,000 tuition, but payment is based on need, so that 45% of Yale’s students do not pay a dime, and a majority receive financial aid. (The New York Times reported the median family income of a student is nearly $200,000, with 19% coming from families in the top one percent of American wealth distribution.) And it’s why Yale’s eating facilities are called “dining halls.” No one would ever dare call them a “college mess.”

❖❖❖

MICHAEL'S NEW YORK

24 West 55th Street

212-767-0555

By John Mariani

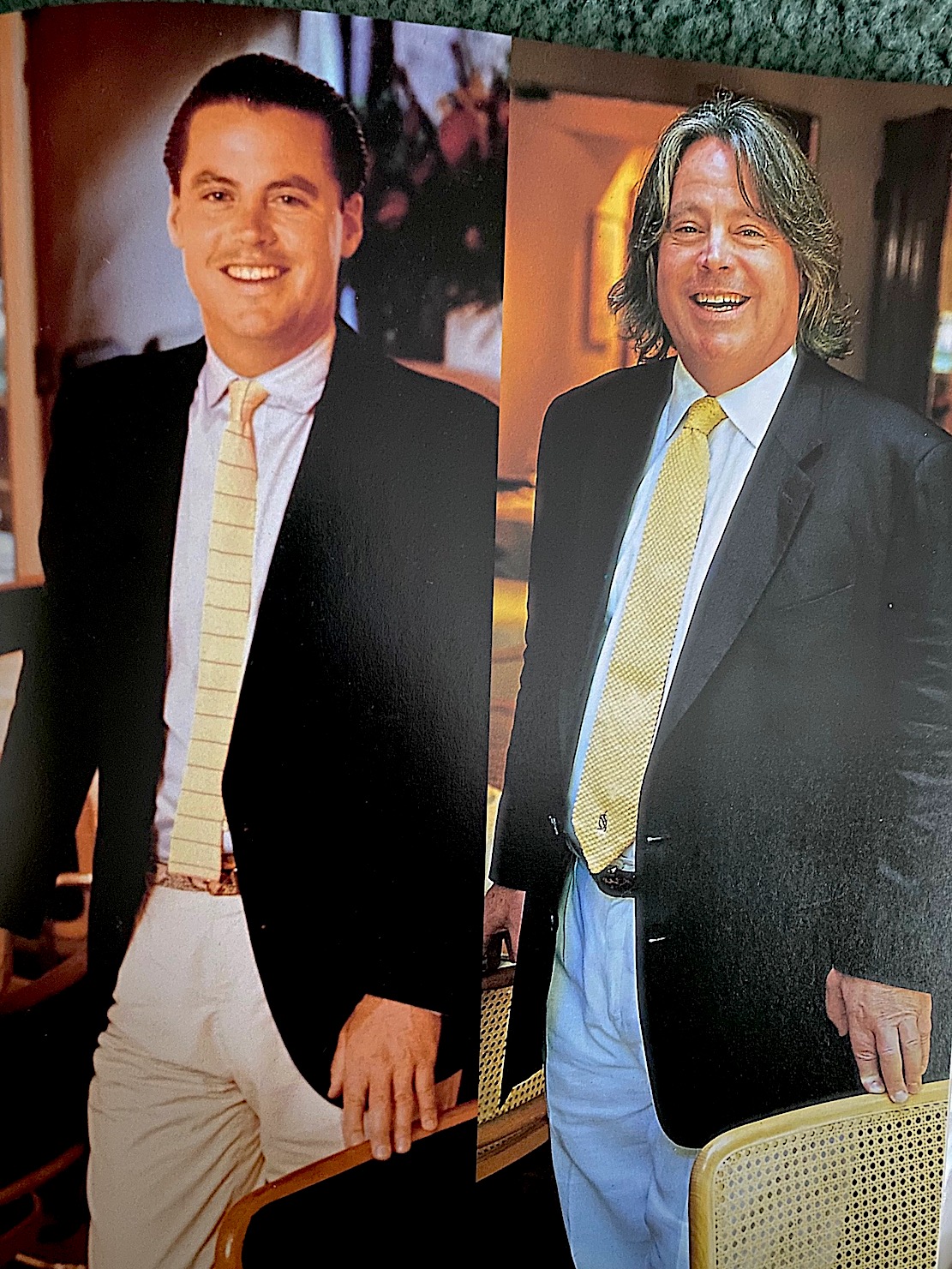

EVEN THOUGH though the story of Michael McCarty has been told many times, his breakthrough on the California restaurant scene was nearly half a century ago and his New York appearance thirty-three years ago, so there’s little news to report. Which is really the point of doing so. As the enduring popularity of McCarty’s two Michael’s restaurants proves, their longevity alone is worthy of high praise.

Both

restaurants look similar and are hung with the works

of once struggling artists that now command millions

of dollars, in New York the walls are hung with

paintings by David Hockney, Jasper Johns, Frank

Stella, Helen Frankenthaler, and watercolors by

McCarty’s wife Kim.

Both

restaurants look similar and are hung with the works

of once struggling artists that now command millions

of dollars, in New York the walls are hung with

paintings by David Hockney, Jasper Johns, Frank

Stella, Helen Frankenthaler, and watercolors by

McCarty’s wife Kim. McCarty, who proudly accepts the moniker wheeler-dealer, readily claims to be a pioneer of California cuisine and style with his big white umbrellas, big white plates, white walls, contemporary jazz and waiters in Polo by Ralph Lauren chinos, pink Oxford shirts and knit ties. Right from the beginning, 1979, Michael’s in Santa Monica took off, manned by young, often inexperienced chefs like Ken Frank and Jonathan Waxman and attracting a celeb clientele that had rarely ventured over the hills (Beverly, that is, and BelAir) to laid-back (gritty) Santa Monica.

The food was French, based on the lighter cuisine of the Riviera, whose climate and laid-back ambience were similar to Santa Monica’s. McCarty, born in Briarcliff, New York, and trained in France, was 24 when he took out a

.jpg) $250,000 bank loan he and his

wife repaid in 18 months. He bought the New York

restaurant location in 1989 after ten years of

haggling with its former owner of the Italian

Pavilion.

$250,000 bank loan he and his

wife repaid in 18 months. He bought the New York

restaurant location in 1989 after ten years of

haggling with its former owner of the Italian

Pavilion. All that’s history, but after all these years, through all the fads and fancies of American gastronomy—the NY Times called Michael’s New York a “trend-immune institution”—Michael’s on both coasts are doing as well or better than ever (after closing in March 2020 on Friday the 13th during the pandemic for 13 months), and McCarty still splits his time between his namesake restaurants, bouncing from table to table to greet and kibbitz with long-standing regulars that in New York have long been the titans of the various media, at breakfast, lunch and dinner.

So, not having been back

since before Covid hit, I thought a return to

Michael’s New York was a good idea as a venue in which

to interview a visiting

California winemaker (who didn’t know anything about

McCarty and had never eaten at his California

restaurant).

So, not having been back

since before Covid hit, I thought a return to

Michael’s New York was a good idea as a venue in which

to interview a visiting

California winemaker (who didn’t know anything about

McCarty and had never eaten at his California

restaurant). Within minutes of our arrival at a packed house, with a private party going on in the rear garden, McCarty was at our table, a good deal heavier but just as ebullient as when he was the skinny 24-year-old in the Armani suits and leopard print shoes he sported when we first met back in 1979. He was quick to tell me his Executive Chef Kyung Up Lim has

been with him for eighteen years;

Manager Steve Millington has been there for 23. Little, it

seems, ever changes much at Michael’s. It’s a tact

that Jonathan Tisch, CEO of Loews Hotels, described

with the Yiddish word heimisch,

“homey.” “Michael has this ability to be very heimisch.”

been with him for eighteen years;

Manager Steve Millington has been there for 23. Little, it

seems, ever changes much at Michael’s. It’s a tact

that Jonathan Tisch, CEO of Loews Hotels, described

with the Yiddish word heimisch,

“homey.” “Michael has this ability to be very heimisch.”

The 600-label wine list is as strong as ever, favoring California bottlings, including some from his own Malibu vineyard, and sommelier Mario Molise is as affable as he is helpful. The lunch and dinner menus are the same, changing seasonally, and still contain signature items. If little of it seems innovative now, it’s like asking why the Eagles keep singing the same 20 hits on tour, which have been covered by countless others.

The

yellowfin tuna tartare with jalapeño, avocado,

Hawaiian ginger and carrot dressing ($26) still seems

a textbook version of a dish now ubiquitous. The kale

salad is Caesar-style, with fennel, pistachio and

Parmesan breadcrumbs ($20), and a new special that

evening was luscious, very rich butternut squash

ravioli ($28). There are three pizzas listed, and none

would win a pizza contest in New York, but the

mushroom pie with fontina, Vidalia onions and thyme

and Iberico salami ($24) is worth sharing.

The

yellowfin tuna tartare with jalapeño, avocado,

Hawaiian ginger and carrot dressing ($26) still seems

a textbook version of a dish now ubiquitous. The kale

salad is Caesar-style, with fennel, pistachio and

Parmesan breadcrumbs ($20), and a new special that

evening was luscious, very rich butternut squash

ravioli ($28). There are three pizzas listed, and none

would win a pizza contest in New York, but the

mushroom pie with fontina, Vidalia onions and thyme

and Iberico salami ($24) is worth sharing. It bears repeating that dishes perfected over 43 years at Michael’s other chefs have tried their hands at, but the crisp-skinned roasted free- range chicken scented with tarragon and sided with spinach ($36) is still a paragon of how all the elements of flavor, texture and juiciness should coalesce in the style of France’s “poulet au grandmère.” The same goes for the massive, tiered burger, which is made with ground ribeye and served with arugula, tomato, onion and pickle on a sesame bun, with either cheddar or Gruyère cheese ($38) that comes with frites that evoke everyone’s guilty pleasure over McDonald’s fries, though these have much more potato flavor. Grilled branzino with capers and spicy salsa verde and charred lemon ($38) was very good, too.

Desserts ($14) are few in number (there’s a cheese selection too), including a flourless dark chocolate cake with whipped cream; a fine crème brûleé; and an Eton mess of autumn berries, crumbled meringue and vanilla ice cream.

Decibel levels have increased everywhere and have done so at Michael’s. Americans didn’t used to be so damn loud, and McCarty believes it’s because they were for so long pent-up inside and get excitable at a restaurant. But the crowd dissipates around 8:30, when the atmosphere becomes more comfortable. And in the garden and outside tables, the noise is considerably dampened.

At a time when so many chefs/restaurateurs are looking to expand operations they have little interest in ever being at, McCarty is seemingly omnipresent in Santa Monica and New York. There had been ups and downs with some projects that didn’t pan out over the years, including a bankruptcy in 1994, aborted plans for a hotel, a devastating fire in 1993 that burned his Malibu house and vineyards down, and a withering Times review in 2008. Asked about that review’s effect, McCarty shrugs: “Five days later Lehmann Brothers collapsed and Bernie Madoff pushed us off the front page, so it had zero effect.”

Now, at

69, McCarty seems as content as a man can be in what

he’s called “the

biggest nickels-and-dimes business you’ve ever seen,”

secure in playing the congenial host every night to

people who have been coming for decades and know him

on a first name basis.

Now, at

69, McCarty seems as content as a man can be in what

he’s called “the

biggest nickels-and-dimes business you’ve ever seen,”

secure in playing the congenial host every night to

people who have been coming for decades and know him

on a first name basis.And so, Michael’s goes on its way and so does McCarty, still boyish in his demeanor, yet a canny professional who has achieved the status of eminence gris without a hint of world weariness. If you like the celebrity aspect to restaurants, his 2007 book Welcome to Michael’s: Great Food, Great People, Great Party! teems with stories, photos and blurbs from the rich and famous. “What I describe as a defining moment is when Michael went from gel in his hair to the dry look,” said Tom Brokaw, “He knew he arrived.”

And somehow, even if you only drop into Michael s’ every five years for a Cobb salad or steak frites, you’ll feel time stand still for two delicious hours.

Open Mon.-Fri. for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Sat. for dinner.

ANOTHER VERMEER

By John Mariani

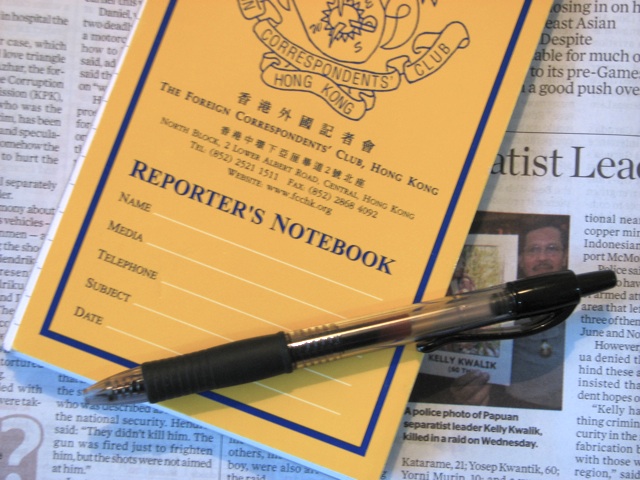

All

the pieces were starting to fit together,

as Katie kept writing furiously in her notebook,

and David was waiting to hear where Shui’s

alleged crimes might come into the developing

picture.

All

the pieces were starting to fit together,

as Katie kept writing furiously in her notebook,

and David was waiting to hear where Shui’s

alleged crimes might come into the developing

picture. “During all those years,” Shui continued, “I have been fortunate to become rather wealthy and, with what my family brought out of China, I have developed quite a large collection. I must not boast, but I believe others will say it is of very high quality. But, of course, I do not have the Vermeer.

“I remember the painting very well. I saw it every day at home. So, when the auction was announced, I knew that I had to have it, not only for sentimental value but because it is by one of the West’s greatest artists. So, in answer to your first question, yes, I will be bidding very strenuously on the Vermeer.”

“Do you think there will be many others?” asked David.

Shui wagged his head and said, “Perhaps not so many. The painting is expected to be very, very expensive, perhaps as much as $100 million, and there are very few people who can bid that high.”

“But you can?” asked Katie.

“I am hoping it will not go that high.”

From this point on, Katie knew she had to be very discreet in her questioning, and she was turning over in her mind whether she should even get further into the “accident” at the hotel. She and David already knew that Shui’s knowledge of the incident was based on an insider reporting back, perhaps the assassin himself, as ordered. Shui’s shock at finding Katie and David in his lobby at ten o’clock that morning was palpable, and Katie sensed he wanted David and her gone as quickly as possible.

She began by flipping through the pages of her notebook and pausing before asking another question—a reporter’s ploy for putting the interviewee ill at ease.

“Now, Mr. Shui,” she began, pausing again slightly, “In your world I’m sure you are familiar with some of the other potential high bidders for the painting.”

“Some of them, I suppose.”

“And you might have known Ryoei Saito of Japan?”

“I did, by reputation.”

Katie tried to play a card she couldn’t really back up: “And did you know Mr. Saito may well have died from arsenic poisoning?”

Mr. Shui’s neck stretched up a little. “No, I did not.”

“How about João Correia, from Brazil?”

“I have never met him.”

“Jan Dorenbosch?”

“Yes, we’ve done business together.”

“Nicholas Danielides, the shipbuilding magnate from Greece?”

“We don’t travel in the same circles, but yes.”

“And how about Igor Stepanossky, who I understand just had a terrible accident while hunting in Croatia?”

Shui seemed to be breaking out in a light sweat on his upper lip. “I do not know him.”

“And . . . last but not least, Leonard Lauden, who also just had a terrible accident?”

Shui looked shaken but in control. “So, Ms. Cavuto, Mr. Greco, it is true what I heard about you. You are making up some kind of crazy conspiracy theory to suit your story. And I sense that you are asking me these questions because you think I am in some way involved in these accidents. Am I correct?”

“I’m sorry, Mr. Shui,” David interrupted, “may I ask just where did you hear that we were making up a conspiracy theory?”

Now Shui was smiling. “Why, from your friend Mr. John Coleman.”

Katie and David snapped up straight. She dropped her pen and said, “Oh my God!” David said, “Holy shit!” Katie’s mind was racing, trying desperately to understand how Coleman could have told Shui about their conspiracy theory. She had voiced her ethical opposition to Coleman about his accepting a trip to Taiwan from Shui, but why would he have arranged for the interview, then warn Shui of their intentions? Katie had not told Coleman about the Chinese delegate’s confession pointing the finger at Shui because David and she had only learned about it that morning from Gerald Kiley.

David spoke first. “What are you talking about, Mr. Shui? How is John Coleman involved in this? He was the one who arranged this interview and you said yes.”

“Yes, and then, just before you left the United States he called to tell me that you are pursuing this wild conspiracy theory that links me to those accidents that have occurred with some of my collector colleagues.”

“Yes, and it is true that we were going to give you the opportunity to answer our belief that you were involved." “Well, of course, your whole theory is preposterous,” said Shui. “I don’t even know some of those people. We are competitive but not cutthroats, Mr. Greco.”

David looked at Katie for a cue to bring in the info they’d received that morning. Katie nodded

“Mr. Shui, we received news this morning from Interpol that you were involved in at least one of the incidents.”

“And which would that be?”

“The attempt to kill Leonard Louden.”

Shui rose from his chair and put his fists on the desk.

“And just what did Interpol tell you?”

Katie spoke. “That a Chinese delegate to the U.N. named Wei Chin was hired by you to assassinate Leonard Louden. Chin escaped from his embassy this week and confessed everything to the F.B.I., Interpol and the I.N.S.”

“I know of no such man,” roared Shui. “And I certainly have no dealings with the Red Chinese delegation. This is a ridiculous accusation.”

“Interpol is taking it very seriously, Mr. Shui,” said David.

“And so are we,” said Katie. “It seems pretty clear to us—and I daresay the Taipei police will soon agree—that those two dead Americans in the Grand Hotel were murdered by someone you hired to create a gas leak in the room you so much wanted us to stay in.”

Shui turned to his associates and began speaking very fast, very forcefully, in Chinese. They responded in monosyllables as Shui kept up his rant. Katie and David sensed the two men were being chewed out for botching the attempted murder at the hotel.

Katie spoke again. “So, Mr. Shui, is our theory completely false? Have you anything to prove otherwise? We don’t know what happened—yet—to Correia and Stepanossky—but we also believe there’s a trail of arsenic leading from this office to Ryoei Saito. It’s all going to be part of my story, unless you convince me otherwise.”

Mr. Shui spoke again to his men, then said, “Ms. Cavuto, I don’t think it will be you who will be writing any such story. If what you say is accurate about your F.B.I. and Interpol information, then I think it prudent on my part to fight such charges vigorously, but not in the American press. I’m afraid you two must leave now. Guanting and Guo will show you out.”

Katie and David looked at each other, thinking, if Shui is just kicking us out of his office, how is he going to stop Katie from writing her article? The answer soon became apparent. As the private elevator came to a stop at the lobby, Guanting said they would be leaving by a rear entrance, out of sight from the desk. The four of them went down a long hall, turned right and headed towards the rear of the building to a heavy security door that Guo opened by putting in code numbers.

Outside were two men dressed in casual clothes, with light overcoats. Guanting spoke to them and both the men opened their coats and pulled out guns. David immediately recognized them as Smith & Wesson Model 10 revolvers.

From behind, Guanting told the two men to use handcuffs, then shoved David towards the men, who handled him roughly in putting on the cuffs. Guo then shoved Katie forwards, knocking her to the ground. David tore himself away from the henchmen and tried to head-butt Guo, but was pulled back and restrained by the men. One of them slapped him hard across the face with the back of his hand and cursed at him in Chinese.

Guo brought Katie to her feet and put the cuffs on her. She looked at David and said, “Are these things always this tight?”

“Yeah, and you’ve got a woman’s wrists. They’re cutting into me,” then, “Hey, don’t worry, Katie. Kiley said Interpol and the Taiwan police will be moving on Shui fast.”

David knew what he said was true enough but not in time to rescue Katie and him from these thugs. He wondered if they were Shui payroll thugs or mob thugs hired by Shui. Probably the latter. Otherwise they wouldn’t have been in place so quickly. They’d be off the books and Interpol and police were unlikely to find them.

The four Chinese hustled Katie and David into a Toyota SUV with its windows blacked out, Katie in the front with the driver, David in back, wedged between the other thug and Guo. Guanting followed in another car.

“Where are they taking us, David? What’ll they do with us?”

“Probably kidnapping us like Correia. We should be okay. They’ll probably let us go after the auction."

“David, that makes no sense and you know it. Shui doesn’t just want us out of the way. I could always write the story after the auction. He wants us permanently out of the way.”

David thought it best to say nothing, keeping his eye on the road, trying to remember the route in case he and Katie were able to break free. He wasn’t surprised they hadn’t been blindfolded, as they would if this were a kidnapping. This was a one-way trip.

© John Mariani, 2016

❖❖❖

NEW BOOK DETAILS HOW CLIMATE CHANGE WILL ALTER

HOW WINES ARE MADE. . . SOONER THAN LATER

AN INTERVIEW WITH BRIAN FREEDMAN

By John Mariani

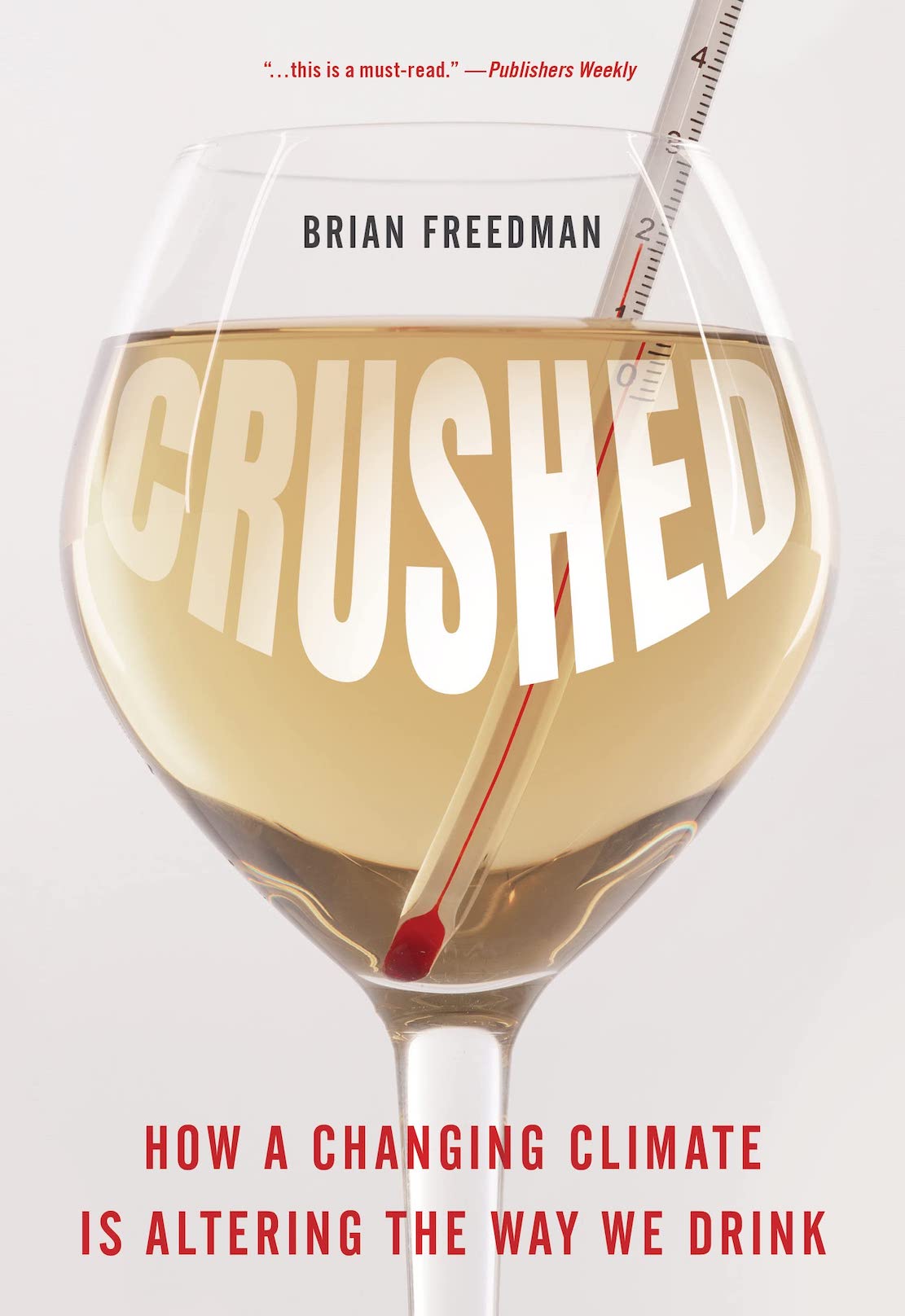

More than most industries, the global wine community has recognized how climate change will radically affect their vineyards, grape growing and flavor of their wines. As a result, many vintners have committed to extensive and expensive programs to ward off the worst effects, at a time when a United Nations report released last week warns that the world, especially richer carbon polluting nations, remains “far behind” and is doing very little to reach any of the global goals limiting future warming.

To gauge just how

serious and diverse the effects might be, I

interviewed Philadelphia-based wine writer Brian

Freedman about his important new book Crushed: How a

Changing Climate Is Altering the Way We Drink

(Rowman & Littlefield).

To gauge just how

serious and diverse the effects might be, I

interviewed Philadelphia-based wine writer Brian

Freedman about his important new book Crushed: How a

Changing Climate Is Altering the Way We Drink

(Rowman & Littlefield).When most people think of climate change they think of global warming. But in terms of some vineyards in some parts of the world, isn’t that a good thing?

In southeastern England, for example, a warming climate is allowing growers there to ripen not just Chardonnay but also Pinot Noir more reliably than in the past. One of the producers I spoke with for the book was even able to bottle a still, red Pinot Noir, which would have been unheard of a generation ago. It's not something he thinks will happen all that often in the short term, but the fact that it did is remarkable. Of course, parts of England hit 40 Celsius (104 Fahrenheit) this past summer, which is terrible for vines, people, everything. And there are now wines being made further south in Patagonia than ever before, and even in Northern Europe, which is fascinating.

The timetable for disaster has increasingly moved up. How are vintners in the forefront of battling climate change?

Many grape growers and winemakers around the world are making serious efforts to farm in a more sustainable manner, to plant vines that are more suited to the changing conditions in their specific locations, to find ways to pivot from the received wisdom of the past in light of the dramatically changing conditions of the present. A winemaker once told me that it's a bit easier for chefs, since they have a new chance every night to succeed, but winemakers have one chance a year, maybe 50 vintages over the course of a long career. That puts even more pressure on them to accept that climate change is not something to pretend isn't happening, and instead find ways to modify existing practices, if necessary, to ensure a successful future.

Is it now possible to theoretically make wine almost anywhere on Earth because of technological advances?

There are extremes of climate where vines just won't grow, and if they do, they won't ripen any kind of usable fruit. I don't see any Antarctic Albariño any time soon coming to a store near you. But as the north and south extremes are warming, the range of locations for growing wine grapes is expanding. And technological advances make it possible to produce pleasant wine from all kinds of grapes. The question, however, is what is wine? Is it just fermented grape juice, or is it an expression of a particular patch of the planet as seen through that fermented grape juice. I firmly believe it's the latter, which means that overly manipulating it in the winery detracts from that. There are also places that are just too hot or dry to grow grapes successfully, and those areas are expanding as well.

What’s wrong with having a wine at 14.5% alcohol and higher?

If the wine is balanced, nothing at all is wrong with a wine at 14.5% or higher. I've had delicious wine that's 15% alcohol and equally delicious wine that's 12% alcohol. The question for me is whether the wine in my glass accurately reflects the place where it was grown and the conditions of that particular vintage. It's also a question of balance: A wine with 14.5% alcohol and not enough acidity may be less pleasurable than a wine at 14.9% alcohol that has well-calibrated acidity to lend a sense of freshness and balance. I tend to drink the vast majority of my wine with dinner, so while I taste wine for work on its own without food, I consume wine with food that hopefully pairs nicely with it. A 14.5% red alongside a perfectly grilled steak sounds great to me ... then again, so does a 12% red!

Do you think California wineries manipulate their wines for popular taste?

Not at all. I think that there are wineries all over the world that have and continue to manipulate their wines to fit perceived popular tastes, but that's not limited to any particular place: It happens in the US, Europe, South American, Australia, anywhere grapes are grown and wine is made. The wine producers that I most respect and that I think offer the most rewards for consumers are the ones that allow their grapes and the conditions of the vintage to speak for themselves. If that means making higher-alcohol wines in a hotter and sunnier year and less-powerful and less fruit-driven wines in cooler or cloudier years, then that's where the real interest comes from., and those producers can easily be found in California, France, Italy, Argentina, Australia, anywhere grapes are grown and wine is made.

.jpg) Since

spirits are distilled, how does climate change

affect them at a time when dozens more distilleries

are being opened in Scotland and elsewhere?

Since

spirits are distilled, how does climate change

affect them at a time when dozens more distilleries

are being opened in Scotland and elsewhere?Climate change-related issues with the farming of cereal grains, whether on smaller farms or commodity-level operations, are rearing their head. Floods, frosts, diseases, plant viruses—it's an issue. Climate change is also affecting the aging of spirits, since their evolution in barrel, if the aging warehouse isn't climate controlled, is deeply affected by temperature and humidity. And one distiller I spoke with, who produces gin, was lamenting the lack of access to certain botanicals last year because a massive storm wiped out much of what he needed to source, and he had to scour the planet to find them. That affects the finished product, pricing, availability, and more.

What changes have allowed Israel’s wine industry to change its image of cheap, sweet kosher wine?

Israel has been producing wine for more than 5,000 years, and it's finally getting the recognition it deserves. It has everything going for it: A wide range of terroirs, from desert to more verdant areas to mountains to coastal climates; a long Mediterranean coastline; and one of the most forward-thinking grape growing and winemaking cultures in the world. Top producers like Tabor, Shiloh, Vitkin, Psâgot, Tulip and more are bringing back a focus on the health of the land in which their grapes grow, on working with varieties that thrive particularly well in the specific micro-climates and soils of the individual vineyards, and working diligently in the winery to express all of that in the finished wine. Israel is also a world leader in the agricultural technology that allows precise monitoring of vineyard conditions, drip irrigation, and more. As a result, the wines are among the most exciting in the world right now. Vitkin produces a stunning Grenache Blanc, Shiloh a phenomenal Petit Verdot, and so much more. The sense of discovery in the world of Israeli wine is unparalleled.

What changes happen in the soil when a vineyard burns down? Does the carbon addition help or hinder?

No one benefits when a vineyard burns down—the loss of life in many cases, of livelihood, is impossible to comprehend. Replanting a vineyard takes immense amounts of money and years of work and waiting. Nothing can justify that.

-1.jpeg)

Since Robert Parker retired has the influence of Wine Advocate waned?

I think that Parker's retirement happened at around the same time that the internet democratized wine criticism. There are, I think, many legitimate arguments to be made against any single person having so much power over an industry, but there are also arguments to be made against exclusively crowd-sourcing wine criticism. My best advice is to recommend that consumers find as many sources for wine advice as they can. There are great critics at the more establishment publications, including Wine Advocate, as well as great ones at online-only and newer sites. The trick is to taste as broadly as possible and find the critics whose palates overlap as much as possible with your own. But I will say this: Few things make me sadder than when I hear someone say they won't drink a wine that was scored below 90 points by such-and-such a critic. Don't be that person! One person's 88 is another's 91 is another's 90. It's wine—explore, experiment, and enjoy it!

Is the planting of too many disparate varietals detrimental to terroir and soil?

Planting different varieties is healthy for the soil, but so is planting single grape varieties, as long as the balance of the ecosystem is respected in both cases. This is why so many growers from California to Italy to Israel and beyond are increasingly planting cover crops, nitrogen-fixing legumes between their rows of vines, working to bring back microbial life in their soil, minimizing chemical inputs and more. You can do that with a single grape variety and you can do that with many varieties planted in the same vineyard. The key, as in everything with wine and life, is balance and respect.

❖❖❖

DEPT OF WRETCHED EXCESS, NO. 678

DEPT OF WRETCHED EXCESS, NO. 678Andy Lansing (left), president and CEO of Levy, will undertake his 20,000-calorie game day tour at Barclays Center ahead of the Nets v Knicks game on November 9th. Levy oversees the culinary outlets at over 250 iconic sports and entertainment venues and marquee events (Super Bowl, US Open, Grammy Awards, Kentucky Derby). This season, Andy resumes his annual ritual of eating his way through every food and beverage item being offered.

❖❖❖

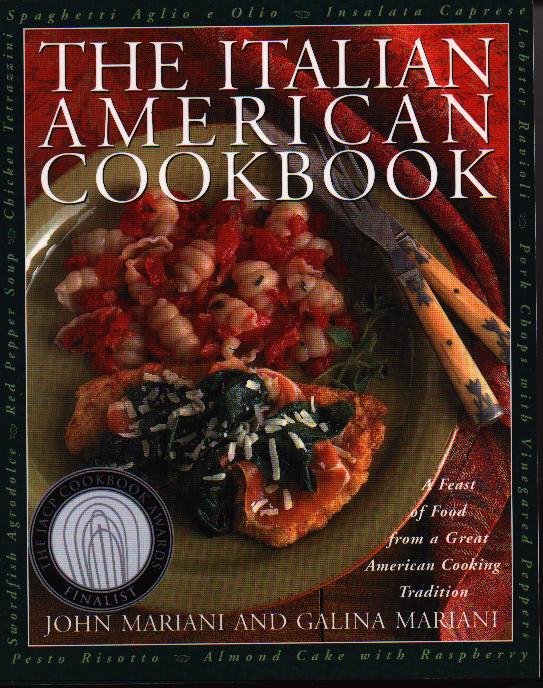

Now in Paperback, too--How Italian Food Conquered the World (Palgrave Macmillan) has won top prize from the Gourmand World Cookbook Awards. It is a rollicking history of the food culture of Italy and its ravenous embrace in the 21st century by the entire world. From ancient Rome to la dolce vita of post-war Italy, from Italian immigrant cooks to celebrity chefs, from pizzerias to high-class ristoranti, this chronicle of a culinary diaspora is as much about the world's changing tastes, prejudices, and dietary fads as about our obsessions with culinary fashion and style.--John Mariani "Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far outnumber their French rivals. Many of these establishments are zestfully described in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by food-and-wine correspondent John F. Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street Journal.

"Equal parts history, sociology, gastronomy, and just plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the World tells the captivating and delicious story of the (let's face it) everybody's favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews, editorial director of The Daily Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating read, covering everything from the influence of Venice's spice trade to the impact of Italian immigrants in America and the evolution of alta cucina. This book will serve as a terrific resource to anyone interested in the real story of Italian food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's Ciao Italia. "John Mariani has written the definitive history of how Italians won their way into our hearts, minds, and stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer, owner of NYC restaurants Union Square Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino. |

|

|

|

|

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish. Contributing Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical Advisor: Gerry McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2022