MARIANI’S

Virtual Gourmet

December 4,

2022

NEWSLETTER

IN THIS ISSUE

JAMES BOND'S TASTES:

THE SPY WHO LOVED ME

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

HINOKI GREENWICH

By John Mariani

ANOTHER VERMEER

CHAPTER 47

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

THE WINES OF PUGLIA

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

biographer

Mary Dearborn on Part 2 of "Ernest

Hemingway: A Life." Go to: WVOX.com.

The episode will also be archived at: almostgolden.

biographer

Mary Dearborn on Part 2 of "Ernest

Hemingway: A Life." Go to: WVOX.com.

The episode will also be archived at: almostgolden.

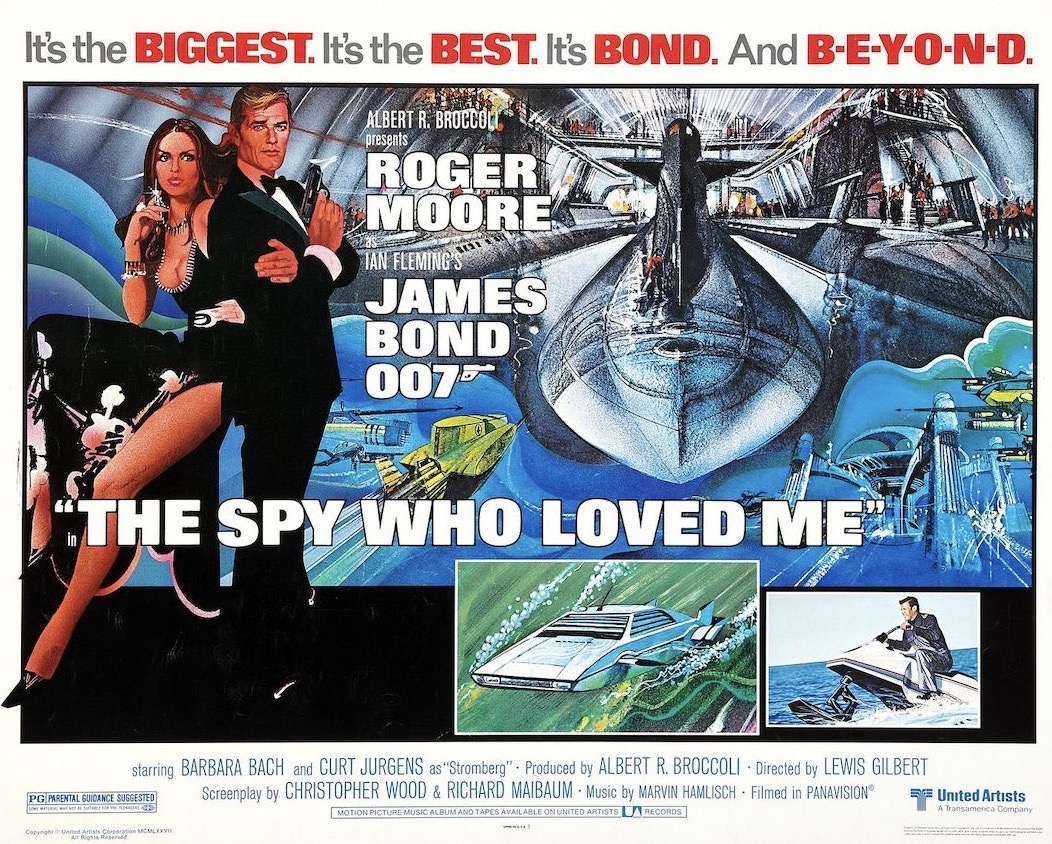

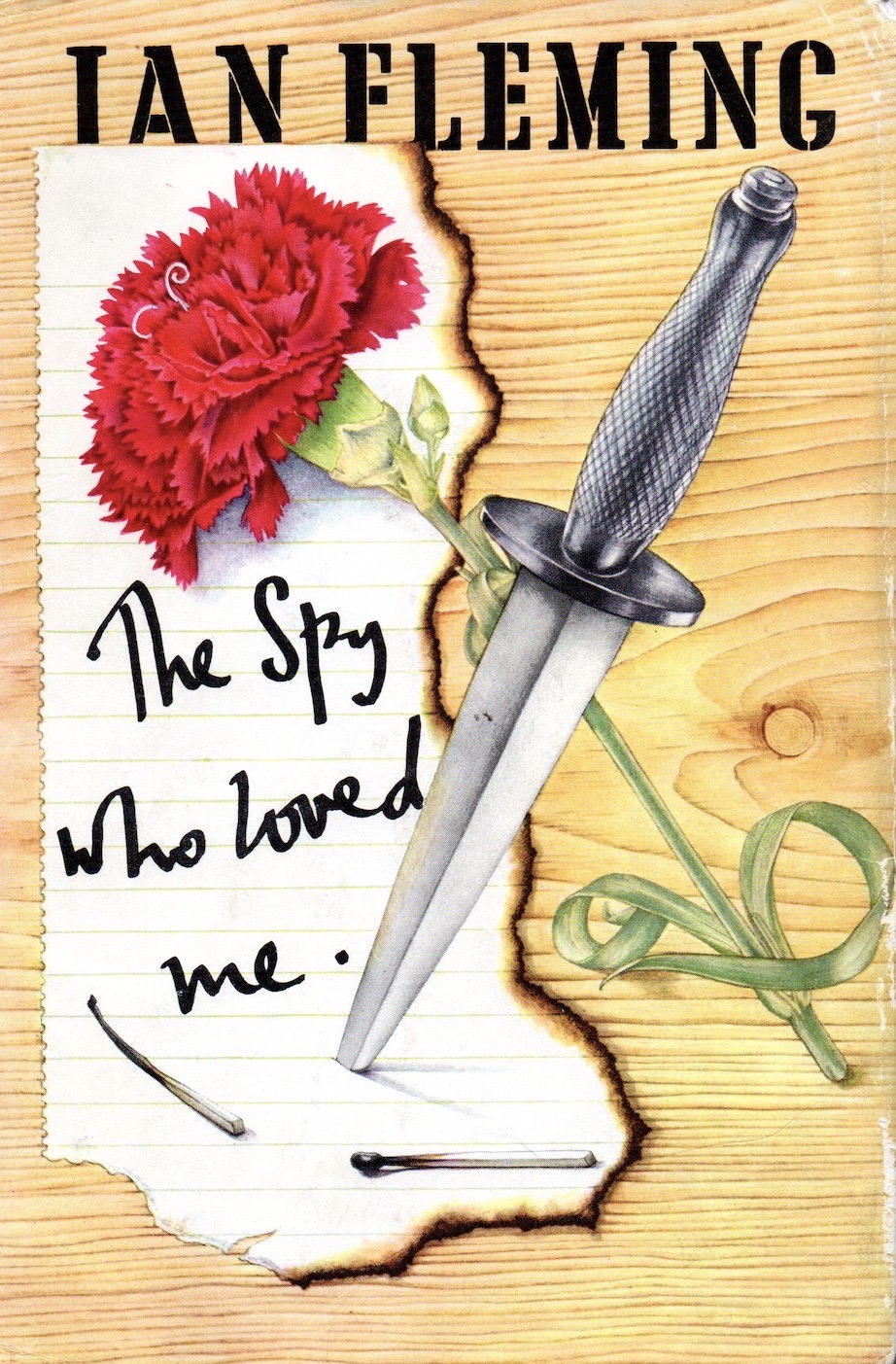

JAMES BOND'S

TASTES:

THE SPY WHO LOVED ME

Ian Fleming’s 1962

James Bond novel, the ninth in

the series, was his own least

favorite, for its experimental

first person narrative of a

Canadian woman whom Bond—who

shows up two-thirds of the way

in—eventually saves from thugs

was not his forte. It received

poor reviews and Fleming

refused to sell the story to

the Bond filmmakers, allowing

them only to buy the title.

The

book’s plot has Viv Michel

reminiscing about failed love

affairs and an abortion she’d had

in Switzerland. She travels

through the Adirondacks on her way

back to her Canadian home,

checking into a motel two mobsters

intend to set on fire to collect

insurance money, with her inside.

Bond appears on the scene only

because, while on his way to

Toronto to pick up a defecting

nuclear scientist, he gets a flat

tire near the motel.

The

book’s plot has Viv Michel

reminiscing about failed love

affairs and an abortion she’d had

in Switzerland. She travels

through the Adirondacks on her way

back to her Canadian home,

checking into a motel two mobsters

intend to set on fire to collect

insurance money, with her inside.

Bond appears on the scene only

because, while on his way to

Toronto to pick up a defecting

nuclear scientist, he gets a flat

tire near the motel.

Bond manages to kill the

mobsters, named Sluggsy and

Horror, then sleeps with Viv,

leaving a goodbye note to her the

next morning. Nothing in the short

novel has anything to do with

Bond’s tastes. There are only

glancing references to Viv

enjoying some pink Champagne, foie

gras, caviar, spaghetti

“bolognaise,” egg-and-bacon

sandwiches and a bottle of

Kentucky Gentleman bourbon.

Neither does the book’s

plot have anything to do with the

movie, the tenth in the series,

which came out in 1977, starring

Roger Moore in his third turn as

007. Given the success of previous

Bond films, The

Spy Who Loved Me had a huge

$13.5 million budget and

involved many international

locations. It went on to gross

$185.4 million worldwide.

In

the movie, Bond investigates the

disappearance of two submarines,

one British, the other Soviet. In

Austria, he is almost killed by

Soviet agents skiing down a

mountain. He is next in Egypt to

find who is selling a sub tracking

system. There he meets the

beautiful Anya

Amasova, KGB agent Triple X

(Barbara Bach), and encounters the

fearsome Jaws (Richard Kiel), a

giant with steel teeth.

In

the movie, Bond investigates the

disappearance of two submarines,

one British, the other Soviet. In

Austria, he is almost killed by

Soviet agents skiing down a

mountain. He is next in Egypt to

find who is selling a sub tracking

system. There he meets the

beautiful Anya

Amasova, KGB agent Triple X

(Barbara Bach), and encounters the

fearsome Jaws (Richard Kiel), a

giant with steel teeth.

Together 007 and Triple X

travel to Sardinia to find a

shipping magnate named Karl

Stromberg (Kurt Jürgens), who had

recently launched a gigantic

supertanker, the Liparus, on which

he is seen having a lavish meal of

lobster, stone crabs, oysters,

poached fish and Champagne, along

with a bottle of Tabasco.

Bond

and Anya must escape Jaws, who is

on a motorcycle, and another

assassin, Naomi (Caroline Munro),

in an attack helicopter.

They escape in a Lotus

Esprit that Q Branch

has converted to drive

underwater.

Anya discovers that Bond

had killed her lover, so she vows

to kill Bond, as soon as their

mission is complete. They board a

submarine to track the Liparus, but are

captured by the crew of the

tanker, from which Stromberg plans

to launch nuclear missiles from

the captured British and Soviet

submarines to obliterate Moscow

and New York, which would trigger

a global nuclear war.

Bond

manages to re-program the

submarines into firing the nukes

at each other, destroying the

subs. He then rescues Anya, kills

Stromburg and drops Jaws into a

shark tank. Anya decides not to

kill Bond, and the Royal Navy

recovers a waterproof pod in which

the two spies are in an intimate

embrace.

Bond

manages to re-program the

submarines into firing the nukes

at each other, destroying the

subs. He then rescues Anya, kills

Stromburg and drops Jaws into a

shark tank. Anya decides not to

kill Bond, and the Royal Navy

recovers a waterproof pod in which

the two spies are in an intimate

embrace.

The film has the most

exotic locales of any in the

series, beginning with Bond’s

skiing away from an overnight

lover, who calls agents to kill

him. The mountain was called

“Berngarten,” but the ski scene

(in which Bond seems to be falling

to his death but is saved by a

Union Jack parachute ) was

actually filmed on the 3,000-foot Asgard

Peak

in Auyuittuq National Park on

the east coast of Nunavut,  Canada.

Canada.

In Egypt, Bond, dressed in

Bedouin robes and looking like

Lawrence of Arabia, enjoys a meal

of fruit in a tent arrayed with

beautiful women he may choose

among. Later, at Cairo’s Mujaba

Club, Anya sips rum on the rocks

and orders Bond his famous martini

“shaken not stirred.” (So much for

his ever traveling incognito.) She

also uses that description when

Jaws gets crushed between a van

and a wall but survives “shaken

but not stirred.”

Outside of town Bond

attends a spectacular son

et lumière filmed at the Giza

Necropolis complex, about 15 miles

southwest of the

city. (Such shows are  still

presented in that location nightly

for tourists.) After he meets

Anya, they drive to Luxor, on the Nile about 450

miles south of Cairo, and find

Jaws stalking them around the Temple of

Karnak.

still

presented in that location nightly

for tourists.) After he meets

Anya, they drive to Luxor, on the Nile about 450

miles south of Cairo, and find

Jaws stalking them around the Temple of

Karnak.

In Sardinia, on the

island’s jet set side of Costa

Smeralda, Bond checks into the

Hotel Cala di Volpe (above).

The final scenes on the water were

filmed off New Providence Island

at Coral

Harbor, where Thunderball and the

opening scene of Casino

Royale had scenes.

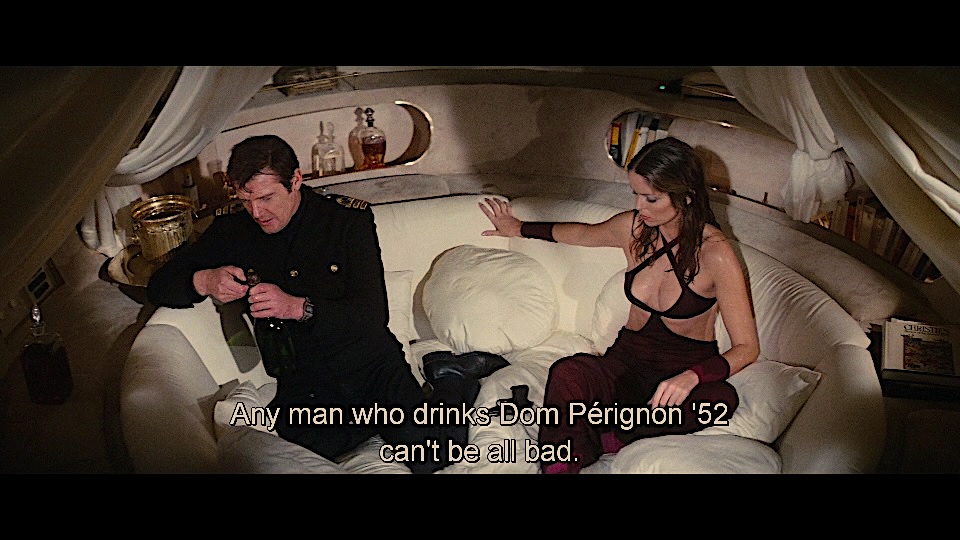

At the movie’s

end, cocooned in their watertight

pod, 007 and Anya sip Dom Pérignon

’52 that Stromburg had stored

there. Bond observes, “Any man who

drinks Dom Pérignon ’52 can’t be

all bad.”

HINOKI

GREENWICH

363 Greenwich Avenue

Greenwich, Connecticut

203-900-0011

By John Mariani

For a relatively small

town—basically, a main street named

Greenwich Avenue—Greenwich, Connecticut, has

a very affluent population. So, all a

restaurateur needs is to find a stylish

niche to fill in order to attract those for

whom caviar, foie gras, wagyu beef and

Champagne are readily affordable.

That was

certainly the thinking behind Hinoki

Greenwich, which was opened last May and was

expanded in September by owners K Dong and

chef Stephen Chen, who realized that there was

a place in Greenwich for an expansive Asian

restaurant that went beyond the sushi bars

already dotted around southern Connecticut. (They

already

have three

restaurant concepts together, a wholesale

seafood distribution company, a few

partnerships and plan to expand Hinoki to

Darien next year.)

That was

certainly the thinking behind Hinoki

Greenwich, which was opened last May and was

expanded in September by owners K Dong and

chef Stephen Chen, who realized that there was

a place in Greenwich for an expansive Asian

restaurant that went beyond the sushi bars

already dotted around southern Connecticut. (They

already

have three

restaurant concepts together, a wholesale

seafood distribution company, a few

partnerships and plan to expand Hinoki to

Darien next year.)

The style, they thought, would nod

towards izakaya

meals, in which many small tastes are offered.

But there would also be a section for sushi and

sashimi,

an array of Chinese dim sum

and several larger courses of a kind not

usually available locally. Hinoki Greenwich

compares  with those

vast, loud Asian nightclubs like Tao, Morimoto

and Buddakan in Manhattan, but without the

madness and party scene those places attract.

with those

vast, loud Asian nightclubs like Tao, Morimoto

and Buddakan in Manhattan, but without the

madness and party scene those places attract.

Hinoki is set in three rooms, one a

bar, another a dining room, and the third,

when it’s up and running, an omakase

dinner room for a chef’s choice menu. The name

Hinoki refers to a wood used throughout that

emits a lovely scent.

What really distinguishes Hinoki is the

quality and sourcing of ingredients. All food

is dependent upon the consistent quality of

product, which huge restaurants needing huge

quantities cannot guarantee. And, when it

comes to raw seafood, there is no margin for

error, which is why most sushi

restaurants’ raw seafood is so often bland. At

Hinoki, the individual flavors of the various

tuna, yellowtail, black cod, king salmon,

fluke and other species are distinct, and

those flavors are enhanced without being

covered up with sauces and spices.

Our

party left choices from every part of the menu

up to Manager Liam Zhang, who first brought a

plate of lustrous baby yellowtail with yuzu

and kosho

chile, a little tomato and, surprisingly,

parmesan cheese ($22). Toro tuna was topped

with truffle oil, olive oil and slices of

Australian black truffles ($28). Thin sliced

salmon mimicked prosciutto set over Asian pear

that looked like melon ($22). Toro

came topped with caviar ($18). A hot appetizer

of duck wrapped pancake ($19) was delicious,

and a “taco” of wagyu beef wrapped in nori

seaweed ($20) was a

Our

party left choices from every part of the menu

up to Manager Liam Zhang, who first brought a

plate of lustrous baby yellowtail with yuzu

and kosho

chile, a little tomato and, surprisingly,

parmesan cheese ($22). Toro tuna was topped

with truffle oil, olive oil and slices of

Australian black truffles ($28). Thin sliced

salmon mimicked prosciutto set over Asian pear

that looked like melon ($22). Toro

came topped with caviar ($18). A hot appetizer

of duck wrapped pancake ($19) was delicious,

and a “taco” of wagyu beef wrapped in nori

seaweed ($20) was a  capital

idea with both crunch and juiciness.

capital

idea with both crunch and juiciness.

There are eight dim sum

choices. We had the very flavorful pork soup

dumpling ($16 for four) that bursts in your

mouth with a rich broth, although the noodle

could have been thinner.

All these preambles to the main courses

were light enough to leave us hungry for what

was to follow. Miso black cod, a meaty fish

with a remarkable silkiness, was grilled after

being marinated in miso and served with

grilled endive ($45), one of the best  renderings of this

dish I’ve had. A tempura-fried branzino with a

lychee sweet-sour sauce ($38) was pleasant

enough, but I found the King crab truffle hot

pot with wild mushrooms, cheese and truffles

more of a hodgepodge of ingredients mixed

together ($39).

renderings of this

dish I’ve had. A tempura-fried branzino with a

lychee sweet-sour sauce ($38) was pleasant

enough, but I found the King crab truffle hot

pot with wild mushrooms, cheese and truffles

more of a hodgepodge of ingredients mixed

together ($39).

The large bar is a splendid design that

takes its shimmer from the bottles of spirits

arrayed, and there are some very rare items up

there, especially among the Japanese whiskies.

The wine list, however, is modest.

On a laid-back Monday the attractive

waitstaff played their part by spending much

of their time at the bar on their cell phones.

Also, depending on the music playing, you’ll

hear either a pounding bass line or some

pleasing sounds of jazz.

Hinoki

Greenwich is a refined and quite

serious Asian restaurant focused on quality,

so that you may well find many of the dishes

on others’ menus, but the flavors have more

spark to them at Hinok, while Chef Chen’s

innovations make it all the more reason to

go.

Open for

lunch and dinner seven days a week.

❖❖❖

ANOTHER

VERMEER

By John Mariani

CHAPTER FORTY-SEVEN

Katie and David thanked the Currens for

all their help and hospitality, and Mrs. Curren

said it had been their pleasure. “We don’t

really get to see that many Americans here,” she

said. “More

Brits than Yanks. Oh, and, David, your new suit

was delivered this morning.”

David wasn’t about to model the new dark

gray suit, but he knew this was by far the

best-fitting suit he’d ever put on. Nothing like

the off-the-rack suits he bought at Men’s

Warehouse on sale that took a beating while he was

on the force. Since retiring, he’d only really

worn a jacket when he was out to dinner with

Katie, and he really was looking forward to

showing himself off in his new threads at the

auction the next day.

That morning, after breakfast, David came

out of his room wearing the suit, trying not to

smile too much.

“My God, David,” said Katie, who was

dressed in a smart shirt-waist blue dress. “You

look fabulous in that suit! Fits you like a

glove.”

David tried to shrug off the compliment,

but he’d never felt better about getting one from

a woman like Katie Cavuto.

Hong Kong’s art galleries and auction

houses were all located in the central part of the

city. Christie’s was on Chater Road, Sotheby’s on

Pacific Place and Crofthouse around the corner on

Star Street. Despite its longevity as an auction

house in Hong Kong, Crofthouse was fairly modest

in size, its offices on the first floor, the

galleries on the second.

The

brochure description of the Vermeer was very

carefully worded and, given British reserve, not

extravagant. It noted the probable date of the

painting, its similarities to The

Astronomer and The

Geographer, and the possibility that it had

been part of a triptych. It did not say how the

painting got to China, or when, only that it was

owned by the People’s Republic of China. Lastly, a

statement of authenticity was made, based on the

150-page experts’ report.

A daytime auction was held, as ever, for

fairly inexpensive or lesser works, while the

evening auction, to begin at 7 o’clock, was

reserved for the best lots of the event, ending

off with the sale of the Vermeer.

Numbered bidding paddles had been handed

out, V.I.P. seats assigned and the room started to

fill up by 6:30. Cameras were not allowed, but

there was an unusual number of journalist, from

the art magazines and the regular Hong Kong,

Chinese and international news organizations, who

had come to see if this would indeed be the

highest price ever paid for a painting.

Katie and David had been there since three

o’clock, anxious to get a quick education on how

auctions were held, observing the ballet that goes

on between auctioneer, his assistants and bidders

in the audience. Clearly, there were bidders who

did not use a paddle but, long known to the

auction house, used personal signals—a finger on

the left cheek, a pen in the breast pocket, legs

crossed or uncrossed—that indicated they were, or

were not, still in the bidding. In the daytime

auctions phone bids were a rarity, but at night

they became a major aspect of the bidding.

Katie knew a few of the journalists in the

room, but David knew no one, feeling like the odd

man out, but he was enjoying being with Katie on a

day when he had no investigating to do. After the

auction, he hoped to take her out to dinner, then

fly home the next day.

The

make-up of the evening audience was fairly well

split between Asians and Westerners, with what

seemed to be small coteries of acquaintances from

the art world, all gossiping about the Vermeer and

what it would sell for. The journalists, including

Katie, were asking them questions, getting

statements, hoping someone would say something

provocative. Many of the Asians came in together,

after having their last cigarettes outside.

The

make-up of the evening audience was fairly well

split between Asians and Westerners, with what

seemed to be small coteries of acquaintances from

the art world, all gossiping about the Vermeer and

what it would sell for. The journalists, including

Katie, were asking them questions, getting

statements, hoping someone would say something

provocative. Many of the Asians came in together,

after having their last cigarettes outside.

The auctioneer was a man who looked quite

young for the job. Derrick Donaldson was standing

off to his side, cupping his hand over a phone,

with another two assistants doing the same. The

auctioneer introduced himself, asked everyone to

be seated, and, without further ado, said, “Lot

223, a Chinese porcelain figure from the late Ming

Dynasty, a very beautiful piece from the

collection of Mr. Edwin Taylor of Hong Kong. Shall

we start the bidding at $15,000?”

For lots expected to sell for under

$100,000 the auctioneer’s first figure was

intended to send a signal as to how high the

increments would be, usually $5,000 to $10,000; if

above $100,000, bidding might go up by $20,000 or

more, if there was plenty of interest in the

piece. If bidding was slow, or none at all, the

auctioneer might make a “chandelier bid” of his

own, pretending someone in the audience or on the

phone had taken the last bid; if the ploy didn’t

work, the auctioneer would snap, “Pass,” and move

immediately to the next lot.

As the evening wore on, with 36 lots to be

sold, the artwork became finer and finer. Aside

from the Vermeer, there were only two pieces of

Western art—a Victorian night table and a small

18th century Italian landscape, both from Hong

Kong sellers. Bids were all over the price range,

with the best Chinese works doing quite well,

others garnering low bids. But as of 8:30, the

excitement over the upcoming Vermeer was palpable,

people whispering, looking over at the box seats

as at the opera, where bidders who did not wish to

be known rustled the curtains drawn in front of

them.

“And now, ladies and gentlemen,” said the

auctioneer, “our last lot of the evening, and one

that I can see is causing a great deal of

excitement in the art world.” Draperies parted

behind the auctioneer and two assistants carried

the painting out and placed it on an easel.

There were audible gasps from the audience,

not only because they were seeing a long-lost

masterpiece for the first time but because it

looked so small—a mere twenty by eighteen inches,

the same as The

Astronomer and The

Geographer—in a remarkably simple gilded

frame. On

size alone, it didn’t look like a $100 million

painting.

The auctioneer made brief remarks about the

painting without extravagant praise, and said,

nonchalantly, “Shall we begin at $50 million?”

One paddle was raised. The auctioneer went

up by $2 million, got a bid, then $5 million,

another bid. Things were going well, and all the

bidding was coming from the floor, beginning with

five paddles, then four, three, two by the time

the bid was $75 million.

“Do I hear $80 million?” The floor bids

stopped, but immediately the auctioneer was being

signaled by Derrick Donaldson that a caller had

come into the action.

“Eighty-five million?”

Another nod, this time from the assistant

on another phone.

“Ninety million?” said the auctioneer.

There was a pause.

The auctioneer looked over at his

colleagues. Nothing.

“Shall we say eighty-seven?”

A nod came.

“Eighty-nine?”

Yes, from Donaldson.

“Ninety? Ninety million dollars?”

Another pause, this one longer. It would be

unseemly for the auctioneer to suggest

eighty-nine-five, but he could clearly tell the

other phone bidder needed to be coaxed.

“We are at eighty-nine million for a unique

painting of a kind that we may never see the likes

of again. No one has bought an authenticated Jan

Vermeer in more than a hundred years. Once this is

gone, there may never be another chance. Will

anyone go to ninety?”

He gazed out over

the audience, which had grown completely silent.

There was no rustling of the box seat curtains.

“We have a bid for eighty-nine million

dollars. Going once. Going twice.” He had

the hammer raised. Then Donaldson waved his hand.

“Ninety!” said the auctioneer triumphantly.

“The bid is at ninety million dollars. Will anyone

go to ninety-five?”

Katie looked at David, wide-eyed.

“Ninety-five,” said the auctioneer, slowly,

sensing the momentum had run its course. “It’s now

ninety million dollars . . . going once . . .”—he

looked at Donaldson and his assistants, all subtly

wagging their heads.

“Last chance. Ninety million dollars . . .

going twice . . .”

Then he slammed the

hammer down.

“Sold

for ninety-million dollars! Congratulations to the

buyer, who has just paid the most money for any

work of art in history. And

Crofthouse is honored to have been the auction

house of record. Thank you, ladies and gentlemen,

that ends tonight’s very exciting auction.”

“Sold

for ninety-million dollars! Congratulations to the

buyer, who has just paid the most money for any

work of art in history. And

Crofthouse is honored to have been the auction

house of record. Thank you, ladies and gentlemen,

that ends tonight’s very exciting auction.”

Katie said, “Wow, ten million shy of what

everyone thought it would go for. I wonder

what happened.”

“Don’t ask me,” said David. “You’d better

schmooze with your colleagues and the other

bidders here, see if you can find out.”

Katie, along with other journalists

present, had already surrounded the five bidders

in the audience, who had gathered themselves into

a discussion of what had just occurred. Katie

identified herself and asked the bidders who they

were or for whom they were bidding.

Two

said they were bidding for anonymous collectors.

One was from the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, one

from the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, and one

from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose

floor bidder was the last to drop out, at $75

million.

Each

was asked if, given their museums’ resources, they

thought they had a real chance of getting the

painting. The people from the Simon and Met

museums said they were not authorized to go beyond

their final bids.

The man from the Getty said, “We might have

gone higher, but you have to be able to judge

where something might end up, and as an

institution, we can’t get into a feeding frenzy.

We felt that the tempo of the bidding indicated

the painting would go much higher.”

“Would you have paid $95 million?” asked

Katie. The man just turned up his hands and said,

“I really can’t comment on that.”

Katie then

went over to Derrick Donaldson, who was in

conference with his auctioneer and several

Chinese, who were there representing their

country’s sale. Donaldson was speaking to them in

perfect Mandarin, obviously trying to explain why

the final bid was so much lower than everyone had

expected. When they’d finished talking, the

Chinese stalked away, still gesturing, and Katie

moved towards Donaldson and asked if they could

speak.

“May I ask you a couple of questions?”

“Sure,” said Donaldson, seeming a little

shell-shocked. “But I can’t tell you who the buyer

is. Both the callers wish to remain anonymous at

this point.”

“Okay, but why do you think the final price

was so much lower than expected?”

Donaldson sighed and said, “Quite simply,

not enough bidders.

We’d anticipated that there were not going

to be any museums able to bid $100 million, and

they must have believed the phone bids would just

keeping going up and up. The two individuals in

the audience who were bidding I do know. One is a

French collector named Branaire, the other

Mexican, name of Santiago. I suppose it just got

too rich even for their bank accounts.”

“I take it Shui didn’t bid,” said Katie.

“Never heard from him.”

“What about Jan Dorenbosch, Nicholas

Danielides, Ivan Stepanossky, Robert Lauden, or

Harry Balaton?”

“I really can’t say, because I don’t know

the answer right now. I can

say we had some preliminary interest from Mr.

Steve Wynn, but he never ended up bidding.”

“And the guys in the box seats behind the

curtain?”

“Never made their move.”

© John Mariani, 2016

❖❖❖

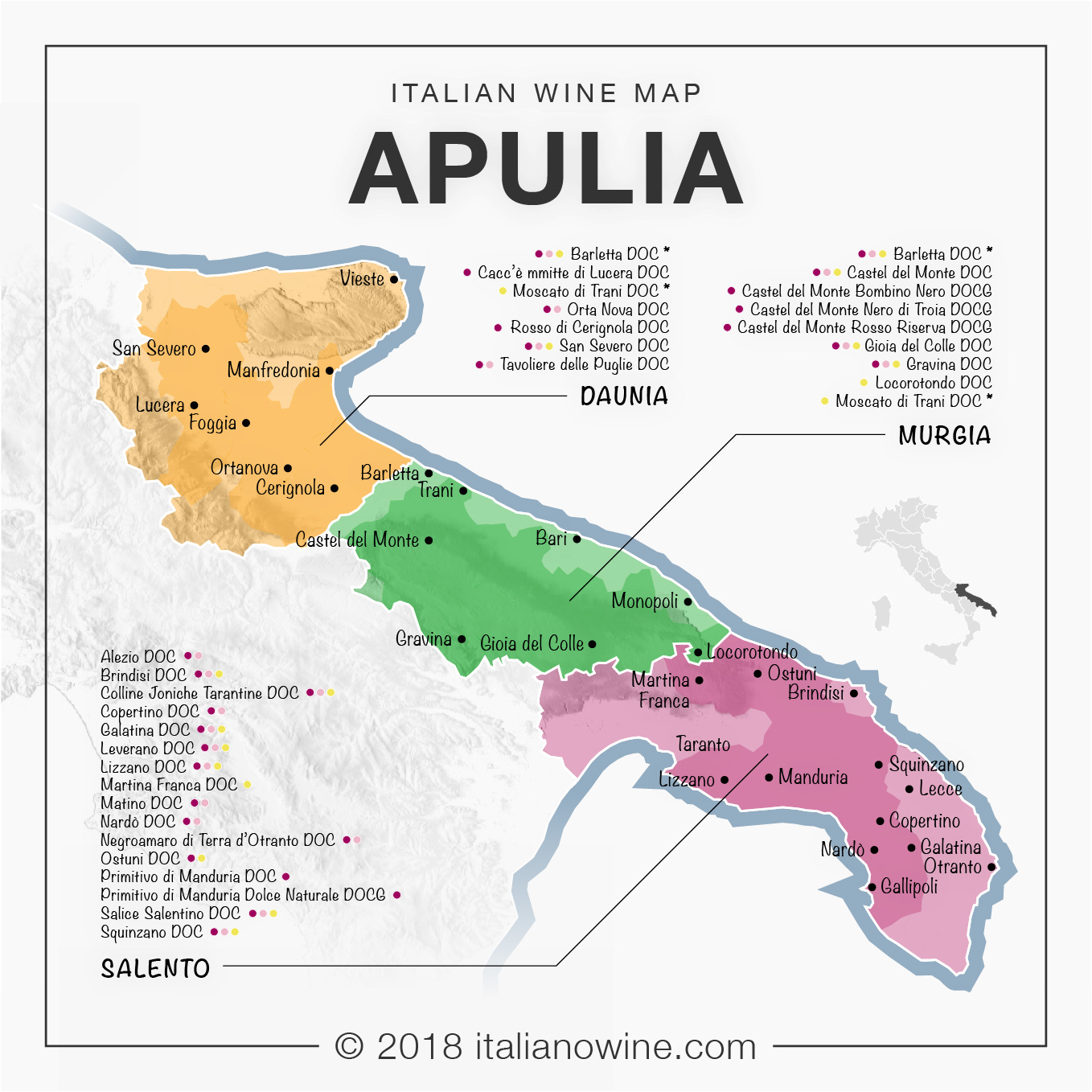

THE WINES OF PUGLIA

By John Mariani

Vineyards in Locorotondo, Puglia

Like Puglia itself—the heel of Italy—its

wine industry has gained both interest and respect

just in the last five years. In the past, large

numbers of cooperatives sold their wines in bulk,

but a younger generation has winnowed down the

best varietals and terroirs to produce excellent

wines that now compete, usually at a more modest

price, in the global market.

Today

Puglia produces 32 wines in the DOC appellation and

four DOCGs, with new IGP wines coming out all the

time. The

manifest success of Puglian wines is clear in its

bottling and export figures. While southern Italy

exports only 6% of its production, 90% of Puglia’s

bottled wine production is sold outside Italy. Plus, Puglia is

now the second largest Italian producer of organic

wines, after Sicily.

Today

Puglia produces 32 wines in the DOC appellation and

four DOCGs, with new IGP wines coming out all the

time. The

manifest success of Puglian wines is clear in its

bottling and export figures. While southern Italy

exports only 6% of its production, 90% of Puglia’s

bottled wine production is sold outside Italy. Plus, Puglia is

now the second largest Italian producer of organic

wines, after Sicily.

Varietals like Negroamaro, Bombino Bianco,

Gravina and Primitivo, once unfamiliar even within

Italy, are now celebrated for their distinctiveness.

Primitivo, once unfamiliar even within Italy, are

now celebrated for their distinctiveness. Primitivo

got a boost when it was found to be a forerunner of

what in the U.S. is called Zinfandel.

Agro-tourism has also been a boon to both the

region and the industry. Murgia, with many Adriatic

microclimates, has proven itself fertile ground for

Primitivo, as well as the Nero di Troia grape, as

the basis for Castel del Monte DOC wines like Rosso

Canosa and Rosso di Barletta, while fragrant white

varietals like Malvasia del Chianti, Greco and

Bianco d’Alessano go into Gravina.

The so-called “Itria Valley Triangle” that

embraces the provinces

of Bari, Brindisi and Taranto produces Martina and

Locorotondo, made principally from white Verdeca and

Bianco d’Alessano grapes. Outside

the “white city” of Ostuni, two indigenous grape

varieties, Ottavianello and Susumaniello, are now

being made in artisanal style and achieving a unique

renown of their own.

Much of the excitement in Puglian vineyards

is due to the appellation IGP (Indicazione

Geographica Produzione), which allows

producers to work with blends outside the DOC rules. A leading

innovator is Gaetano Marangelli (above) of

Cantine Menhir Salento in the southeastern part of

Salento, who is dedicated to inclusiveness of

viniculture and agro-tourism. “Fifty years ago all

the wineries also produced their own olive oil,

cheese, even chickens and eggs,” he says. “I and

some of my colleagues are trying to re store that.”

store that.”

To such end his property is home

to a 40-hectare organic farm named “Anna” that

supplies many of the provisions to the on-premises

Origano Osteria & Store, which also has a small

restaurant, and he is building a 30-room hotel. His

flagship wine, with only 15,000 bottles produced

annually, is the Pietra Primitivo Susumaniello,

which I would rank with many of the finest red wines

in Italy. If there were such a class as “Super

Puglians,” this would be one of them.

While recently in Puglia I also visited the

Vallone estate, dating to the second half of the

19th century, when Commendatore Vincenzo De Marco

began the production and marketing of bulk wines to

France and Tuscany.

The marriage of Donato Vallone to Marco’s

daughter Maria brought in the Flaminio Estate of

Brindisi to the family, and later, at the end of the

‘60s, the Castel

Serranova estate was added, now totaling 500

hectares.

Over a buffet lunch at Vallone’s estate (below),

my wife and I sampled wines obviously made by

oenologist Severino Garofano according to all modern

technologies. Balanced and distinctive as local

varieties, they went splendidly with Puglian

cheeses, meats and pastas presented.

I was very impressed by the Graticciata Rosso

IGP Salento, using

dried Negroamaro grapes from the 'Caragnuli'

Cru, an 80-year-old Apulian sapling vineyard in San

Pancrazio Salento.

After six years of experimenting, the wine

has emerged as a voluptuous and strikingly big wine

at 14.5% alcohol.

Castel

Serranova is a Cru from a vineyard called Vigna

Castello, the origin of the most classic of the

Salento blends, namely Negroamaro and Susumaniello. Vallone

makes both a red and a lovely rosé from the

Susumaniello, using the traditional static draining

technique to give complexity. Flaminia, from an

estate near Ostuni, is another line of the Vallone

wines using the grape Ottavianello, with a wonderful

perfume, similar to France’s Cinsault.

Castel

Serranova is a Cru from a vineyard called Vigna

Castello, the origin of the most classic of the

Salento blends, namely Negroamaro and Susumaniello. Vallone

makes both a red and a lovely rosé from the

Susumaniello, using the traditional static draining

technique to give complexity. Flaminia, from an

estate near Ostuni, is another line of the Vallone

wines using the grape Ottavianello, with a wonderful

perfume, similar to France’s Cinsault.

Vallone is dedicated to the balance of nature

within the vineyards, including the reduction of

unwanted invasive insects. “We used a spray that

confuses the males sexually, so they don’t mate,”

Francesco Vallone told me, “and out of fear our

workers put on masks and gloves so the same would

not happen to them.”

These innovations caused Vallone to diverge

from the strict DOC regulations. “We want to be IGP,

because we want to do what we want. We don’t want to

be judged under DOC bureaucratic standards.”

Of particular note is a new emphasis on rosé

(rosato)

wines in Puglia. Given the wide variety of red

grapes in the region,

innovative winemakers have picked up on the current

fashion for rosé as a year-round wine, not one just

for summer months. Since Puglia’s rosés differ so

widely, from pale pink to deep rose, there are

different levels of complexity and intensity, so

that they go especially well with the bounty of

seafood that is the mainstay of the region’s

gastronomy.

in the region,

innovative winemakers have picked up on the current

fashion for rosé as a year-round wine, not one just

for summer months. Since Puglia’s rosés differ so

widely, from pale pink to deep rose, there are

different levels of complexity and intensity, so

that they go especially well with the bounty of

seafood that is the mainstay of the region’s

gastronomy.

Rosés made

from Nero di Troia are particularly rich—they are

called the ”black rosés of Troy.” As with many

“lost” varietals, Bombino Nero was rediscovered in

Puglia and is one of the principal grapes used for

rosés, acquiring a prestigious DOCG appellation for

Bombino Nero Rosato Castel del Monte.

Tuccanese is also a re-discovered grape,

thought to be a clone of

the hearty Sangiovese.

Aleatico,

of Greek origins, is considered a

semi-aromatic grape variety, derived from Moscato,

and having a wonderful perfume. It is grown for DOC

wine in the areas of Bari, Brindisi, Taranto, Lecce

and Foggia. The Primitivo, whose resurrection as a versatile

grape has led to innovations, produces a bold,

deeply colored rosé with plenty of spice.

Ottavianello has also had a resurgence in the

current century, especially around Brindisi, often

made in a light, pale style with good

aromatics.

As recently as 2015

the authoritative

Oxford

Companion to Wine warned

that, “what Puglia urgently needs is to

ensure the survival of its centenarian bush vines

and most interesting indigenous varieties, and,

ideally, a viticultural in winemaking institute . .

. to shape its future.” That future has arrived far

more quickly than anyone could have imagined.

INJURED IN THE INCIDENT

“Yesterday, we had a customer come in and order takeout, a barbecue plate and a couple sides,” said Ashley Holt, whose mother, Debbie Holt, owns Clyde Cooper’s Barbecue in Raleigh and interacted with the customer. “She left and came back and said her barbecue was undercooked because it had a lot of pink in it. We explained that’s because it’s smoked. When pork is smoked, it turns pink.” Holt said a few minutes later a Raleigh Police officer came to the restaurant, talked to the customer outside and then entered Clyde Cooper’s, asking about the pork.

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las

Vegas

Eating Las

Vegas

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher

Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish.

Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2022