❖❖❖

THIS WEEK

JAMES BOND'S TASTES

THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN GUN

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

LA PULPERIA

By John Mariani

GOING AFTER HARRY LIME

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

MORE BANG FOR THE BUCK

By John Mariani

Judy

Carmichael. Go to: WVOX.com.

The episode will also be archived at: almostgolden.

Judy

Carmichael. Go to: WVOX.com.

The episode will also be archived at: almostgolden.

❖❖❖

JAMES

BOND'S TASTES:

THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN GUN

By John Mariani

The

Man with the Golden Gun

(1965) was Ian Fleming’s twelfth and last Bond

novel (published posthumously), and it was

fairly limp (and poorly reviewed) by

comparison to its antecedent, You Only

Live Twice, in whose ending the British

spy was r ecovering in Japan

from amnesia and needed to go to Russia to jog

his memory. The Man with Golden

Gun slides over whatever happened there,

opening with the news that MI6 presumed 007

dead for more than a year, only to find him

return so brainwashed by the Russians that he

tries to assassinate his boss M with a cyanide

pistol.

ecovering in Japan

from amnesia and needed to go to Russia to jog

his memory. The Man with Golden

Gun slides over whatever happened there,

opening with the news that MI6 presumed 007

dead for more than a year, only to find him

return so brainwashed by the Russians that he

tries to assassinate his boss M with a cyanide

pistol.

After being “de-brainwashed,” Bond is

back on the job, sent to Jamaica (a frequent

Fleming location) to kill Francisco “Pistols”

Scaramanga, a paid assassin of several British

agents. He is known as "The Man with the Golden

Gun" because his preferred weapon was a

gold-plated Colt .45 revolver with solid-gold

bullets.

Bond is said to be still drinking too

much, but there are few references to his

appetites in the book; he still favors bourbon

over Scotch and Champagne over all. M, over

lunch at his club Blades, orders an Algerian

wine called Infuriator, which Bond loathes.

Scaramanga prefers Jamaican Red Stripe

beer.

prefers Jamaican Red Stripe

beer.

Bond masquerades as Scaramanga’s personal

assistant at his bordello in the Thunderbird

Hotel, where 007 is welcomed with a meal of eggs

Benedict and a bottle of Walker’s Deluxe

bourbon. Bond learns that Scaramanga is involved

with a syndicate of American gangsters and KGB

agents. Not much of a world-shattering threat

here: Scaramanga and his investors want to

increase the value of the Cuban sugar crop, run

drugs and prostitutes into the U.S.

Over lunch with Scaramanga, Bond orders

Beefeater’s pink gin with “plenty of bitters” to

go with shrimp cocktail, steak and French fries.

Bond meets up

with his CIA friend Felix Leiter, pretending to

be an electrical engineer in Scaramanga's

meeting room, where Leiter learns that

Scaramanga plans to kill Bond. At dinner in the

hotel dining room, the meal consists of “desiccated

smoked salmon with a thimbleful of small-grained

black caviar, filets of some unnamed native fish

(possibly silk fish) in a cream sauce. A ‛poulet

suprême’ . .

. and the bombe surprise.”

Bond meets up

with his CIA friend Felix Leiter, pretending to

be an electrical engineer in Scaramanga's

meeting room, where Leiter learns that

Scaramanga plans to kill Bond. At dinner in the

hotel dining room, the meal consists of “desiccated

smoked salmon with a thimbleful of small-grained

black caviar, filets of some unnamed native fish

(possibly silk fish) in a cream sauce. A ‛poulet

suprême’ . .

. and the bombe surprise.”

After a KGB agent exposes them, Leiter

and 007 manage to kill many of the bad guys and

hop aboard Scaramanga’s train, where Bond, even

during a gunfight, fantasizes about a meal of

cold lobster salad, cold cut meats, pineapple

and local fruit, roasted in a stuffed suckling

pig with rice and peas, and champagne, rum punch

and Tom Collins cocktails. Both Bond and

Scaramanga are wounded, and Scaramanga limps off

into the swamps. When Bond finds him, he is

eating a boa constrictor and drinking its blood,

offering some to Bond, who replies, “No thanks.

I prefer my snake grilled with hot butter

sauce.”

The villain offers Bond

money—he refuses—and asks Bond not to kill him

in cold blood and to allow him a moment to

pray—“I’m a Catholic!” he declares—but then

pulls out a golden derringer with a snake venom

bullet and shoots Bond, who returns fire, kills

his foe, then collapses in pain.

It

takes weeks for Bond to recover fully, and then

M offers him a knighthood, which 007 mulls over,

saying it makes him shudder at the thought of

being called Sir James Bond.

The

1974 film made from The Man

with the Golden Gun was

the ninth, and Roger Moore’s second appearance

as the British agent. The plot had nothing to do

with the book’s, as became the standard practice

in subsequent Bond films. There is little

reference to food and drink, though right at the

movie’s beginning Scaramanga’s midget

assistant/henchman Nick Nack (Hervé Villechaize)

brings a tray of Moët Champagne and a bottle of

Guinness Stout with oysters to Scaramanga

(Christopher Lee) and his moll, Andrea Anders

(Maud Adams).

Bond is sent to find

Scaramanga (who is known to have a third nipple)

after MI6 receives a golden bullet etched with

“007” on it. Bond retrieves another golden

bullet from a belly dancer’s navel. (She, too,

is partial to Moët; Bond orders Dom Pérignon at

his hotel; both are Moët brands, which tells you

something about product placement). The bullet

is traced to a gun maker in Macau.

Accompanied

by Andrea, Bond goes to Hong Kong and checks

into the Peninsular Hotel (left), then

goes to the Bottoms Up Club, where Nick Nack

steals a high energy device called the Solex

Agitator. Bond is arrested for pulling his own

gun outside the club, but the Hong Kong police,

led by Lieutenant Hip, bring him to meet M and Q

onboard the RMS Queen

Elizabeth, which, after

a fire in 1972 capsized and

Accompanied

by Andrea, Bond goes to Hong Kong and checks

into the Peninsular Hotel (left), then

goes to the Bottoms Up Club, where Nick Nack

steals a high energy device called the Solex

Agitator. Bond is arrested for pulling his own

gun outside the club, but the Hong Kong police,

led by Lieutenant Hip, bring him to meet M and Q

onboard the RMS Queen

Elizabeth, which, after

a fire in 1972 capsized and  was left

rotting in the Kowloon harbor. There he is

ordered to retrieve the Solex Agitator.

was left

rotting in the Kowloon harbor. There he is

ordered to retrieve the Solex Agitator.

Posing

as Scaramanga (complete with fake nipple), Bond

flies to Bangkok to meet entrepreneur Hai Fat,

who had the scientist who created the Solex

killed. Bond’s plan fails when Scaramanga

himself is found to be operating at Fat's estate

at Dragon Garden, Castle Peak Road, Castle Peak.

Bond is then captured and sent to a martial

arts academy at Muang Boran, where students are

instructed to kill him. Bond

fights two of them and is then

rescued by Hip and two teenage girls trained in

martial arts.

and is then

rescued by Hip and two teenage girls trained in

martial arts.

Fat’s

men follow Bond, who escapes on a motorized sampan

on Bangkok’s canal system. He reunites with his

assistant Mary Goodnight, with whom he has a

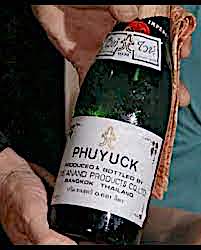

dinner at the Oriental Hotel, where the waiter

offers them a bottle of Phuyuck ’74 (the same

year as the movie) wine.

Scaramanga

kills Fat and obtains the Solex. Anders begs

Bond to kill Scaramanga, and promises to get the

Solex, but she is murdered at a Muay Thai boxing

event at the Lumpini Stadium the next day. Bond

does obtain the Solex with the help of

Goodnight, who is kidnapped by Nick Nack, with

Bond in pursuit, not, however, in his usual

Aston Martin but instead in a borrowed AMC

Hornet.

the help of

Goodnight, who is kidnapped by Nick Nack, with

Bond in pursuit, not, however, in his usual

Aston Martin but instead in a borrowed AMC

Hornet.

Bond takes a seaplane to Scaramanga's private

island at Phang Nga Bay, where Nick Nack

receives him with a bottle of Dom Pérignon ‘64

(Bond says he prefers the ’62). Scaramanga

destroys Bond’s plane with his Solex laser,  then,

over a lunch of mushrooms and other delicacies,

Bond comments on his host’s choice of wine,

“Hmm, slightly reminiscent of the ’34 Mouton.” Scaramanga

says “I must get some for my cellar.”

then,

over a lunch of mushrooms and other delicacies,

Bond comments on his host’s choice of wine,

“Hmm, slightly reminiscent of the ’34 Mouton.” Scaramanga

says “I must get some for my cellar.”

He then proposes a duel on

the beach. After pacing off, 007 finds

Scaramanga has vanished. Nick Nack leads Bond

back to  Scaramanga’s house,

which has a fun house of mirrors and diversions.

Bond manages to kill Scaramanga and retrieve the

Solex, blowing up the island and taking his

foe’s Chinese junk to escape with Goodnight for

an eight-hour sail to Hong Kong.

Scaramanga’s house,

which has a fun house of mirrors and diversions.

Bond manages to kill Scaramanga and retrieve the

Solex, blowing up the island and taking his

foe’s Chinese junk to escape with Goodnight for

an eight-hour sail to Hong Kong.

NEW YORK CORNER

LA PULPERIA

623 Ninth Avenue

646-669-8984

.jpg)

No one is sure how Hell’s Kitchen, the

neighborhood bound by the Hudson River on the

west, 30th Street on the south and 59th Street

on the north, got its name. Some say it’s a

tangling of the name of a 19th century German

restaurant, Heil’s Kitchen, others because of

its disrepute as a crime-ridden area. Yet, even

though real estate developers dub it “Clinton,”

no New Yorker uses that name.

Whatever its

origins, Hell’s Kitchen has long been a section

teeming with restaurants of every stripe, not

least the Jewish delis of the Garment District.

These days it is more diverse than ever, with a

slew of new Latin American restaurants that add

measurably to the area’s gastronomic clout.

Whatever its

origins, Hell’s Kitchen has long been a section

teeming with restaurants of every stripe, not

least the Jewish delis of the Garment District.

These days it is more diverse than ever, with a

slew of new Latin American restaurants that add

measurably to the area’s gastronomic clout.

La Pulperia is very much one of those

showcasing a panoply of regional cuisines, based

on the creativity of Executive Chef Miguel Molina,

who hails from Guerrero, on Mexico’s

west coast. He arrived in New York in 1996 and

worked in French and Italian restaurants

throughout Manhattan and Brooklyn, and now creates

his own ideas from a long career that began on his

parent’s farm restaurant.

The interior of La Pulperia has a maritime

motif throughout, but I wish that the designer,

Andres Gomez, had put more thought into the

acoustics, for this is a very loud restaurant with

booming music, whose 88 decibels equate to the

sound of a bulldozer coming through the room. I

happened to be dining with an interior designer,

who said the room had not a single soft, sound-absorbing

surface or anti-buffering components that would

lessen the noise and heighten the joviality of the

place.

room had not a single soft, sound-absorbing

surface or anti-buffering components that would

lessen the noise and heighten the joviality of the

place.

That said, the food is terrific. Tuna con

Tomate (right) is a twist on the

simpler, traditional pan con

tomate found in Spain; pan-seared tuna is

sliced thin and placed on toast with a spicy salsa

made of grated heirloom tomato, lemon zest,

garlic, parsley, chives and aleppo

peppers ($20). Croquetas de

Bacalao stay more traditional and are

wonderful to bite into as long as you know they

are piping hot, filled with salted cod and served

with citrus aïoli ($15).  Smoky

sun-dried tomato tapenade is the base for a

yellowtail hamachi tostada,

with avocado, jalapeños, and radishes, topped with

crispy fried leeks and ancho chile powder ($20).

Smoky

sun-dried tomato tapenade is the base for a

yellowtail hamachi tostada,

with avocado, jalapeños, and radishes, topped with

crispy fried leeks and ancho chile powder ($20).

The

ceviches are glistening fresh, and the mixto ($19)

is the best way to sample the range, as a cocktail

made with shrimp, white fish, squid, jalapeño, red

onions, cilantro and avocado. Parsnips add a sweet

flavor to grilled octopus, along with a dash of

white truffle oil, shaved fennel and caramelized

onion (($27).

Another mixto of seafood (right),

cooked as a main course and intended for two or

more, is a Brazilian favorite composed of abundant

squid, langoustine, mussels, white fish, scallops,

clams, cod and peppery Spanish chorizo in a

dandelion-based broth, topped with green

coconut-cilantro rice ($38). Argentina adds to the

menu with a huge parrillada

(priced for two at $110, but it can feed three or four

handily) of New York strip sirloin, skirt steak,

short ribs, chicken, chorizo, morcilla,

salsa criolla, papas à la Provençal, and a

green salad spiked with  chimichurri.

The

simplest entrée is the day’s whole fish, expertly

deboned (market price).

chimichurri.

The

simplest entrée is the day’s whole fish, expertly

deboned (market price).

Desserts ($12) include a “Volcano

Chocolate” lava cake exuding dulce de leche,

topped with orange mascarpone cream. I can never

refuse hot, fried churros

fritters, which are eaten throughout the day in

Spain, and are served with a rich, warm dulce de

leche.

You’d expect an array of fanciful cocktails

and won’t be disappointed, along with both white

and red sangria. They also stock dozens of

tequilas and mezcals that would take weeks to go

through.

La Pulperia is one of those New York Latino

restaurants that show a range of foods

and ingredients you’d have to travel throughout

Central and South America to find with such

radiance and creativity.

Open for dinner nightly; brunch

Sat. & Sun.

GOING AFTER HARRY LIME

By John Mariani

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Joseph

Southey called Leonid Lentov to ask if

he’d see the two Americans and was not surprised

when the Russian said he would be very happy to

do so. David

followed up and was equally surprised when

Lentov did not even ask why David was calling,

saying only, “Yes, yes, Southey told me about

you. Come over whenever you want. I may have

some good stories for you.”

As a detective David was always

suspicious of people who too readily volunteered

information, not least those who might have

something to gain from being so readily open to

questions. He also knew not to trust everything

any spy would tell him because such people were

trained liars, and often intertwined fact and

fiction after many re-tellings of so many “good

stories” that the truth was often no more than a

kernel in a rotted-out cob of fictions.

Still, David was one of the best at

clearing away the outright fabrications of

informers and cutting closer to what probably

happened. David knew that the more a person

spoke voluntarily the more likely he was to

provide good leads while trying to embellish his

own importance. The more they gave an

interrogator, the more informers believed they

would be believed. But with spies—and David had

no particular experience interrogating them—the

game was different. Agents—especially double

agents--were trained to undergo interrogation,

even torture, knowing full well that they only

needed to hold up as long as it seemed plausible

that they could stand no more pain. Of course,

the interrogators were well aware of this, too,

which made the whole thing of questionable

value. And

the informers always had good stories set to be

told, some actually the truth, some even

exposing their colleagues to danger, just enough

to make them sound cooperative. It was all part

of the training.

David was well

familiar with such tactics, but he always asked

himself, what’s in all this for the person under

scrutiny? Is he really giving up under duress?

Or is he begging for mercy in order to spread

dis-information? Or does he really want to get

free of his criminal past and gain protection

from the interrogators? It

could be a combination of all of those reasons,

but saving one’s dignity never had anything to

do with any of them. Sometimes money did.

David was well

familiar with such tactics, but he always asked

himself, what’s in all this for the person under

scrutiny? Is he really giving up under duress?

Or is he begging for mercy in order to spread

dis-information? Or does he really want to get

free of his criminal past and gain protection

from the interrogators? It

could be a combination of all of those reasons,

but saving one’s dignity never had anything to

do with any of them. Sometimes money did.

In the case of Leonid Lentov there was no

question of offering him money, first, because

there was no money to offer and, second, unlike

in police dealings with criminals, bribery was

completely forbidden under the journalistic code

Katie lived by. The most she could do was buy a

source a meal or a few drinks. Money

was never promised or passed in an envelope.

Lentov didn’t sound like he expected any.

Southall (above) was a suburban

part of London not in line for gentrification.

It was poor, with a large enough complement of

Indians to earn the nickname “Little India.” For

that reason, the storefronts were crucibles of

aromas floating out into the street air—scents

of cumin, fenugreek, cardamon, roasted peanuts

and sesame seeds, the same smells David

remembered from the Indian restaurant he’d eaten

at on Brompton Road. The grocery store signs

were written in Punjabi, the DVD stores were

plastered with posters of Bollywood stars, and a

pub called The Glassy Junction  even

accepted rupees.

even

accepted rupees.

In every

way the settling of Leonid Lentov in Southall

was a form of secluded banishment by MI6. For,

although he was in no danger of being

assassinated by the Soviets, shunting him out of

the center of London was both prudent and a

deliberate snub to a man for whom MI6 had no

further use, much as the KGB did with Kim

Philby. Out of sight and mind.

There was no tube station at Southall, so

Katie and David took a train out of Paddington

Station, a fifteen-minute ride, arriving at a

small brick-clad station with bilingual signs in

English and Punjabi. Lentov’s flat was about

five blocks away, but he’d asked the two

Americans to meet him at The Glassy Junction on

South Road.

The pub was in a nondescript three-story

building topped with a sign saying GLASSY

JUNCTION in English and a larger-than-life

cut-out of a mustachioed, turbaned Sikh above

the entrance. Katie and David went inside to

find the pub looked like so many others, except

there was a Sikh behind the bar, a painting of

cows above the bar and Indian pop music playing.

From a rear corner table a large man was

gesturing to them to come over. Though bearded,

the man was clearly not a Sikh.

“Welcome!” the man said in a booming,

accented voice. “I am Leonid Lentov, and you

must be the Americans who called me.”

Katie and David introduced themselves and

sat down in the booth where Lentov had been

drinking a pint of ale. He got up to greet them,

six feet-four inches of him, with a beard

somewhere between Rasputin’s and Andrei

Solzhenitsyn’s in length, gray and unkempt, as

was his rough tweed jacket. Lentov’s

face, however, showed no trace of peasant blood:

Very handsome, with high cheek bones, thick

black brows and eyes that had the glint of a fox

rather than a wolf in them, as if you had to pay

strict attention to see if they ever blinked. It

also seemed clear to Katie and David that

alcohol had worked its way deep into his

demeanor and physical appearance. A

century before he might have been White Russian

but he was born under the U.S.S.R. and grew up a

good Communist.

“So

how do you know my friend Southey?” he asked,

signaling the bartender to bring two more ales.

David explained how they’d come to meet

Southey through Frank English, and how Southey

had said Lentov would be a good source for

Katie’s story.

“So you are a journalist,” he said as a

statement to Katie, “and you, sir, are an ex-New

York City policeman?”

“I was chief detective investigating mob

activities there, yes.”

“Italian Mafia, correct?” Lentov’s

English was excellent—he had been in the

diplomatic corps—with just a slight rolling of

his r’s and hard s’s. “Pretty

soon

you won’t have to worry about them in New York

anymore. The Russian Mafia will push them out.

Armenians and Albanians, too. They are the worst

of all. Kill their own brother for nothing.”

“Italian Mafia, correct?” Lentov’s

English was excellent—he had been in the

diplomatic corps—with just a slight rolling of

his r’s and hard s’s. “Pretty

soon

you won’t have to worry about them in New York

anymore. The Russian Mafia will push them out.

Armenians and Albanians, too. They are the worst

of all. Kill their own brother for nothing.”

David needed to save face, saying, “Oh,

yeah, they were in my sights, too.”  He then rattled off the names of some of

the eastern European gang leaders. “Armen

Kazarian (left), Razhden Shulaya (right),

a lot of other creeps. I retired a few years

ago, so I haven’t kept in touch.”

He then rattled off the names of some of

the eastern European gang leaders. “Armen

Kazarian (left), Razhden Shulaya (right),

a lot of other creeps. I retired a few years

ago, so I haven’t kept in touch.”

Lentov smiled and leaned back on the

tufted banquette. “So, what do you want to know?

About Graham Greene? I knew him a little.

Burgess and MacLean? I was just entering service

when they escaped. Philby, him I knew well.”

Katie and David had discussed beforehand

that they would allow Lentov to tell his own

story before getting into the one they were

pursuing. David suspected that this was not

Lentov’s first drink of the day and that the

Russian would be more forthcoming as the

afternoon went on. David paid for Katie’s and

his ales and gave the bartender a fifty-pound

note, indicating he should keep the pints

coming. Katie was supposed to charm Lentov

before asking the questions she needed answers

to.

“Just to fill in some background, Mr.

Lentov,” she said, “I’d like to know more about

your own career and how you got to this point in

your life.”

Lentov finished his glass and called for

another. “Beware such questions—may I call you

Katie?—because Russians like nothing more than

talking about themselves, especially when their

lives were, shall we say, put in jeopardy. We

all grow up believing we are guilty of

something.”

“We have all day,” said Katie, thinking

that her own Catholic upbringing had instilled

the same feelings of guilt.

And so for the next

hour and a half Leonid Lentov spoke of his life,

one that had come to a dead end too early,

especially after enjoying the perks of being in

the Soviet diplomatic corps in London after the

war, where he'd lived off and on in the 19th century

Victorian mansion, in Kensington Palace

Gardens, the largest building on the street (left).

And so for the next

hour and a half Leonid Lentov spoke of his life,

one that had come to a dead end too early,

especially after enjoying the perks of being in

the Soviet diplomatic corps in London after the

war, where he'd lived off and on in the 19th century

Victorian mansion, in Kensington Palace

Gardens, the largest building on the street (left).

In

so many ways Lentov seemed destined for the kind

of life most Russian could barely dream of. His

family had, indeed, been white Russians—the name

given to those who opposed the Communists during

the Civil War—but bribery had brought them

through the worst of it, and Lentov’s father,

who spoke perfect French and English, worked his

way up into the diplomatic corps, where his son

Leonid was expected to follow. Highly

intelligent and ambitious, Leonid Lentov rose

quickly within the Soviet system, even as he

clung to the idea that he was superior to all

his communist superiors.

Another round of drinks arrived.

“I knew that eventually I would be tapped

by the K.G.B. to work as an agent in London,” he

said. “Everyone was. It was no secret. The

British knew we were all spies to one degree or

another, and we knew that many of our opposites

in Moscow were MI6. It was all a game. Very few

people got hurt.”

“So, you mean, if you or your opposite

were discovered to be a spy, you wouldn’t be

executed?” asked Katie.

Lentov laughed. “Of course not! We were

too valuable alive. That’s why it was such a

tremendous shock and embarrassment for the Brits

to lose not just Burgess and MacLean but also

their handler, Kim Philby. It was a farce and

many heads rolled at MI6—figuratively speaking,

of course.

The only time anyone was executed was if

one of your own people was found to be a double

agent, like those three were. They all would

have hanged if they’d been arrested.”

“So catching you was something of a coup,

then,” said David, using a slight bit of

flattery.

Lentov shrugged. “I was not a big fish.

But I would rather have stayed in London once I

was found out than go back to Moscow, where I

would be living like a peasant for the rest of

my life.”

Lentov looked around the pub and said,

“Of course, living the way I do out here is not

what I expected, but it’s a much better life

than I would have had in Moscow, or wherever the

Soviets would have sent me.”

“So, you were offered a deal by British

Intelligence,” said Katie.

Lentov nodded and said, “It was probably

time for me to jump anyway. By the 1980s I’d

become completely disillusioned with the

Communist ideologues running my

country—Brezhnev, Andropov, Chernenko. Philby

would rage at the TV every time Brezhnev (right)

would come on. Men of no intelligence, mere

bureaucrats with no idea of what was going on in

the rest of the world. Gorbachev did, of course,

but by then I was working for MI6 as a double

agent.”

Lentov described how the Brits had shoved

him into a car, brought him to MI6 and

confronted him with the evidence that he had

been responsible for the arrest of two of their

agents in East Germany and threatened him with a

life sentence in prison if he did not cooperate.

“The choice was easy,” said Lentov. “I

was getting older, I enjoyed my life here in

London, had no family, and came and went pretty

much as I wished. My spying for the Soviets

rarely involved anything as important as my

exposing those two British agents—for which I

was highly praised by Moscow but got nothing

from it—and the Brits were only asking me to

stay put in the Soviet Embassy here and feed

them information.”

The arrangement didn’t

last long. After three years Lentov was due to

be re-assigned to a post in Pakistan he had no

interest in taking.

“I’m sure the Soviets were on to me by

then,” he said, “so I told my MI6 handlers the

game was over.

And here I am, living in Southall,

drinking in an Indian pub, telling my sad story

to two Americans.” He raised his glass and

toasted in Russian, “Nasdrovia!”

Although David was well familiar with why

turn-coats—whether against the crime mobs or

intelligence agencies—were spared assassination,

though it was not clear to Katie.

“So you never felt you had to look over

your shoulder after the Soviets found out about

you?” she asked.

Lentov chuckled. “Thank

you for your concern, Katie, but in my line of

work, I was always looking over my shoulder.

Now, like so many other former spies, I am a

toothless dog. I know nothing, I have access to

nothing, and, like Kim Philby, I am worth

nothing to anyone. And the Cold War is long

over. We are all good friends now, correct?”

That was Katie’s opening to begin her

line of questioning about Philby, or anyone else

that Graham Greene might have known in the

K.G.B. right after the war.

“Well, then,” she began. “As someone who

was in London all that time and knew all the

agents and double agents, as well as Philby and

Graham Greene, can you throw any light on what

I’m looking for? I assume you’ve seen the film The

Third Man?”

It was clear that the alcohol was having

little effect on Lentov but he seemed very happy

to tell Katie and David whatever they wanted to

know—although David suspected Lentov might also

tell them a lot of what he thought they’d want

to hear.

“The movie was very close to the way

things operated after the war,” said Lentov.

“Greene had been in MI6, you know, so he got the

details right.”

“Would that include criminal activities

like selling bad penicillin on the black

market?” asked David.

“Very probably,” Lentov answered. “But

that would be what you call chicken feed

compared to other drugs.”

“And so you think Greene would have been

right to think the Soviets would provide a safe

refuge for Harry Lime in their sector?”

“Absolutely! As they say in the movie,

everyone in Vienna was involved in the black

market, but the Soviets had the means and power

to make it flourish and to take their unfair

share of the profits.”

“So, in effect,” said Katie, “Harry Lime

was working with and for the Russians.”

Lentov nodded and said, “But let’s

remember that Lime was a fictional character,

Katie. But, if he did exist, yes, the Russians

would in all likelihood be his benefactors. They

would take their cut, yes.”

“So,” Katie asked slowly, “do you think

Greene based Lime on anyone he knew in Vienna?

Could it have been Kim Philby?”

Lentov reminded the Americans that Philby

was not known to have been anywhere near Vienna

in those days, and, he said, “It’s difficult for

me to believe that he could be acting as a

double agent somewhere else and still have time

to run a drug operation in Vienna.”

“True,” said David, “but we’re not

looking for an exact identification with Lime.

If Greene already knew—or even suspected—that

Philby was a double agent while continuing to

befriend Greene, do you think it possible that

it could have been the case that Philby was

involved as well in the black market in Vienna,

or anywhere else in Europe, after the war.”

Lentov sat back, breathed deeply, looked

at his watch, then called for another pint.

“Let me tell what I know of Philby,

before and after his escape from Beirut,” said

Lentov. “You know, before I was outed as a spy,

I could travel back and forth to Moscow and,

since I’d known him in London, I was able to

visit him at his flat. I found him almost as

fascinating as Greene did, but Philby and I both

used Greene as a mouthpiece. He was such a

gullible man. When Greene died, I felt rather

sorry for him.”

Lentov went on to describe Philby as a

master of disguise—not make-up and wigs, but in

changing his physicality to put a person at ease

upon meeting them while at the same time

impressing them with his personal charisma.

Philby was handsome, well read, well traveled,

and, among his colleagues at MI6, deeply

respected for his insight. How many times had he

saved comrades’ lives by his ingenuity, getting

them out of harm’s way with uncanny precision—as

he had with Burgess and MacLean! How fine a

family man he was when he married for the second

time and fathered five children! A drinker who

never seemed to get drunk! A man who could speak

with authority on the best hotels, the best

hunting rifles, the best coffee in Venice, the

finest restaurant in Istanbul! Yes, were a

novelist to choose the ideal British spy, Kim

Philby would have been ideal.

“Philby’s greatest gift was to appear to

be your very good friend,” said Lentov. “ I

thought he was to me. Even after I became his

opposite—a Russian who spied for the British—we

had a marvelous relationship. It’s not all that

unusual among retired spies, you know. Rather

like RAF pilots buying drinks for Luftwaffe

pilots they shot down in the war and vice versa.

Philby never accused me being a turncoat. He

knew how the game worked. Mostly we just talked

about the old days. Of course, his old days were

far more exotic than mine.”

Katie interrupted, “Is it true that—at

least from all I’ve read and gotten from

others—that, although he insisted he never gave

up his ideals about communism, he was a very

sad, disillusioned man at the end of his life.”

Lentov shook his head and said, “Philby

ended up like me. His ideals? I don’t know. His

benefactors at the K.G.B. certainly did not

treat him the way he had hoped. He became a

heavy drinker.”

Lentov told of how Philby had expected

full military honors on his return to Moscow,

and perhaps a position high in the senior

rankings of the K.G.B. Instead

he was ignored, and, with his third wife—a

Russian twenty years his junior—he lived in a

small, dreary flat near Pushkin Square, with

little or no access to the outside world except

via mail—all of which was censored, coming in

and going out, including Graham Greene’s many

letters. The K.G.B. told Philby

they had information that MI6 was going to try

to assassinate him, so he needed full-time

guards to protect him.

When visitors—Lentov excepted—sought to

visit Philby, they would be met at the Moscow

airport and put in a taxi whose driver pulled a

curtain and was not allowed to speak except by a

car phone with authorities. At

Philby’s address, the visitor was greeted by a

K.G.B. agent and escorted upstairs to the flat. At an

exact, pre-appointed time, the visitor was

required to leave, first frisked to see if

Philby had given the visitor something to get

out of the country.

“I saw him perhaps six times in all those

years before I myself was moved out here to

Southall,” said Lentov. “Then I was allowed no

contact with him whatsoever. Greene

might have before he died.”

Katie and David seemed drained by

everything Lentov had told them. Katie even felt

a little sorry for Philby, while David knew that

was part of Lentov’s intent. Yet, despite it

all, they were still no closer to Harry Lime

than before.

Katie thanked Lentov for everything he’d

shared with them, then said, “Well, I suppose

this is still very much a mystery. If only we

could actually talk to Kim Philby, have him shed

light on it all.”

“Well,” said Lentov, “that would be very

difficult to arrange.”

“Especially since Philby’s dead,” said

David.

Lentov smiled, paused, then

said, “Oh, Philby’s not dead.”

© John Mariani, 2016

❖❖❖

MORE BANG FOR THE BUCK

By John Mariani

Given their rarity—usually by

design—great wines are made to be expensive: the

2019 DRC’s Romanée-Conti is currently selling at

$34,000, and it’s nowhere close to being ready to

drink. But there are also too many wines whose

makers think they should be getting prices above

$100 a bottle merely on chutzpah. More sensible

vintners know they will sell more good wine when

it’s priced more amenably. Here are several that

make very good sense and are worth every penny.

Given their rarity—usually by

design—great wines are made to be expensive: the

2019 DRC’s Romanée-Conti is currently selling at

$34,000, and it’s nowhere close to being ready to

drink. But there are also too many wines whose

makers think they should be getting prices above

$100 a bottle merely on chutzpah. More sensible

vintners know they will sell more good wine when

it’s priced more amenably. Here are several that

make very good sense and are worth every penny.

FULLDRAW FD2 2018

($55)—This young Paso Robles Willow Creek District

AVA owned by Connor and Rebecca McMahon produces

Rhône varietals, like this well fruited Grenache and

Syrah. This is a boutique winery founded ten years

ago on a 100-acre site with rich limestone that

provides their wines  with a brisk minerality. The price

is just right for this caliber of Rhône Ranger,

which are too often big bombs of little finesse.

with a brisk minerality. The price

is just right for this caliber of Rhône Ranger,

which are too often big bombs of little finesse.

ALKINA KIN SHIRAZ 2021 ($36)—

FEL

WINE ANDERSON VALLEY CHARDONNAY 2021 ($34)—I am

among many who have long criticized so many

California Chardonnays for tasting like candy-coated

charred oak, but FEL enjoys the Anderson Valley cool

climate to produce far more balanced wines sourced

from Ferrington Vineyard.

This Chard spends a long 10 months sur lie

aging and fermenting in neutral French oak.

Director of Winemaking Ryan Hodgins and winemaker

Sarah Green insist on a "hands off" approach in

the cellar, so the wine does not taste manipulated

to taste a particular way, letting Nature takes

its course instead.

CHAMPAGNE

GREMILLET ($40)—In the rarified culture of

Champagne, where houses measure their esteem by

centuries, Gremillet,

in Aube, is a late bloomer, having been

founded only in 1978. Their blends come exclusively

from the first pressing and have a longer aging

process than the AOC rules suggest, i.e., 22

months for their non-vintage Champagnes, which is

where the bargains are. Jean-Michel Gremillet

received 30 acres of vines (most in Côte de Bars)

from his mother, Lulu, and now his eldest son,

Jean-Christophe, is cellar master. Because

they are not bound by old traditions, Gremillet

still experiments year by year and now has an array

of Champagnes in their portfolio, all costing about

$40-$50.

CHAMPAGNE

GREMILLET ($40)—In the rarified culture of

Champagne, where houses measure their esteem by

centuries, Gremillet,

in Aube, is a late bloomer, having been

founded only in 1978. Their blends come exclusively

from the first pressing and have a longer aging

process than the AOC rules suggest, i.e., 22

months for their non-vintage Champagnes, which is

where the bargains are. Jean-Michel Gremillet

received 30 acres of vines (most in Côte de Bars)

from his mother, Lulu, and now his eldest son,

Jean-Christophe, is cellar master. Because

they are not bound by old traditions, Gremillet

still experiments year by year and now has an array

of Champagnes in their portfolio, all costing about

$40-$50.

BODEGA TRIVENTO RESERVE

MALBEC 2021

($11). I don’t know who pronounces such things, but

April 17 has been declared Malbec World Day, which

is a good enough excuse to enjoy this underrated

varietal that grows well in Argentina. Trivento is

the country’s best selling winery. With such clout

it can appeal even to vegans because the wine is

fined without using animal by-products. Whatever. At $34

this is a remarkable Malbec, which is a dark

blending varietal in Bordeaux but here shows nuance

and levels of rich flavors that will go well with

any red meat (which is ironic, vegans don’t eat meat

and don’t know what they’re missing.)

MACROSTIE SPARKLING BRUT

2019 ($48)—The options for those who don’t want to

pay Champagne prices for a fine sparkling wine are

now myriad, and MacRostie’s 2019 is testament to

advances made in the category. Following her

reputation for making highly valued Pinot Noirs and

Chardonnays, winemaker Heidi  Bridenhagen

made this cuvée of those two varietals from San

Giacomo Vineyards for the Chardonnay and Thale’s

Estate for the Pinot Noir. Nature delivered a fine

growing season in Sonoma in 2019, so delicacy could

be achieved without sacrificing good fruit. After

tirage, the wine was aged for 30 months to develop

flavors and aromas. It makes a fine aperitif with

just about any first course as well as seafood.

Bridenhagen

made this cuvée of those two varietals from San

Giacomo Vineyards for the Chardonnay and Thale’s

Estate for the Pinot Noir. Nature delivered a fine

growing season in Sonoma in 2019, so delicacy could

be achieved without sacrificing good fruit. After

tirage, the wine was aged for 30 months to develop

flavors and aromas. It makes a fine aperitif with

just about any first course as well as seafood.

CROSSBARN SONOMA COAST

PINOT NOIR 2020 ($37)—Paul Hobbs, whose namesake

winery is among my favorite California estates,

founded Crossbarn in 2000, beginning with Cabernet

Sauvignon, and is now making a range of wines that

include this well priced Pinot Noir . Balance is

what I seek in Pinot Noir, which is a tricky wine to

get right, but this one has the right fruit and acid

in tandem with a structure of tannin. It’s

interesting to find that Crossbarn’s website

recommends this wine with pizza with sausage,

bucatini all’amatriciana and five-spiced braised

pork shoulder, with which I heartily agree.

NIPPOZZANO VECCHIE

VITI CHIANTI RUFINA 2019 ($23)—The highly promoted

virtues of Chianti  Classico have become so

hazy because of changes in the D.O.C.G. rules that

backing away to sample some of the bottlings from

the less well-known regions of Tuscany that make

Chianti is all to everybody’s benefit—especially

since Rufina itself is

now in the D.O.C.G. category. It’s made from

Sangiovese and other local varietals and is a label

with the famous Frescobaldi vintners umbrella. The

wine spends aging time in both barrels and bottle,

emerging at an ideal 13.5% alcohol to give it both

body and layers of peppery flavors characteristic of

Chianti.

Classico have become so

hazy because of changes in the D.O.C.G. rules that

backing away to sample some of the bottlings from

the less well-known regions of Tuscany that make

Chianti is all to everybody’s benefit—especially

since Rufina itself is

now in the D.O.C.G. category. It’s made from

Sangiovese and other local varietals and is a label

with the famous Frescobaldi vintners umbrella. The

wine spends aging time in both barrels and bottle,

emerging at an ideal 13.5% alcohol to give it both

body and layers of peppery flavors characteristic of

Chianti.

DR.

KONSTANTIN FRANK CÉLEBRÉ RIESLING CREMANTE ($25)—Dr.

Konstantin Frank has been an innovator for many

decades in New York’s Finger Lakes and this superb

100% Riesling displays the tantalizing quality of

this tangy varietal. The grapes are very lightly

pressed, with the secondary fermentation taking

place in bottle for a minimum of 24 months. The

slight sweetness is very appealing, as you’d find

in first-rate Trocken German Rieslings. It’s good

for a feast, not least with shellfish, fishes like

salmon and blue-veined cheeses.

❖❖❖

BLOCK

THAT METAPHOR!

BLOCK

THAT METAPHOR!

"One of Mr. Torrisi’s gifts is his ability to let

you taste two ideas at once, as if he were playing a

harmonic line under the melody. Some of his dishes

remind me of Brian Wilson’s songs. They can have a

gentle, lyrical and introspective feeling while

showing a remarkable grasp of techniques that can be

used to achieve new effects. (Mr. Carbone, in this

scenario, is Mike Love, or at least his positive

traits; the restaurant that most clearly bears his

imprint, Carbone, is a master class in manipulating

the appeal of shared memories, good times and fun,

fun, fun.)." Pete Wells, NY Times (3/1/23)

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher

Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish.

Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2023