MARIANI’S

Virtual Gourmet

MARCH

1, 2026

NEWSLETTER

Founded in 1996

ARCHIVE

❖❖❖

THIS WEEK

Back in the Golden Age of Greenwich Village

in the 1960s, You Could Find All the

Great Folk Singers of the Era and Eat Well at

Legendary Restaurants. You Still Can.

By John Mariani

THE BISON

CHAPTER TWELVE

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

DAN DUCKHORN, NAPA VALLEY MERLOT PIONEER, DIES AT 87

By John Mariani

Back in the Golden Age

of the 1960s,

You Could Find All the Great Folk

Singers

of the Era and Eat Well at

Legendary Restaurants.

You Still Can.

As one of

New York’s oldest neighborhoods, dating back

to the end of the 17th century,

Greenwich Village had, since the 19th

century, become an enclave for the avant garde

and what was called bohemianism––it was at one

time or another home to Mark Twain, Robert

Louis Stevenson, Henry James, Walt Whitman,

Hart Crane, Eugene O’Neill, Jackson Pollock

and Andy Warhol. And for more than a century

its layout of winding and crisscrossing

cobblestone streets has changed not at all,

and height restrictions have kept its hamlet

charm intact.

Back in the

Sixties the Village was at its height as a

crucible for folk music and jazz talents who

played in a slew of clubs––none of them

swanky–– that included The Village Gate, The

Village Vanguard, The Bitter End, Café Au Go

Go, Café Wha? and The Bottom Line, where I, as

college student would go to see emerging acts

like Joan Baez, Peter, Paul & Mary, Dave

van Ronk, Nina Simone and Bob Dylan. Many of

those clubs had no liquor license so your

options were soft drinks spiked with

rum-flavored syrup or coffee brewed sometime

earlier in the day.

Back in the

Sixties the Village was at its height as a

crucible for folk music and jazz talents who

played in a slew of clubs––none of them

swanky–– that included The Village Gate, The

Village Vanguard, The Bitter End, Café Au Go

Go, Café Wha? and The Bottom Line, where I, as

college student would go to see emerging acts

like Joan Baez, Peter, Paul & Mary, Dave

van Ronk, Nina Simone and Bob Dylan. Many of

those clubs had no liquor license so your

options were soft drinks spiked with

rum-flavored syrup or coffee brewed sometime

earlier in the day.

Having little money to blow, I still

was able to have a good meal in a myriad of

places, most of them Italian given the

Village’s adjacency to Little Italy. Few were

distinguished but they were all extremely

cordial, the décor dated but cozy and a carafe

of wine cost just a few bucks.

The fare at the oldest bar in New York, The White Horse Tavern (567 Hudson Street) wasn’t the draw for beat poets like Jack Kerouac and Irish scribes like Brendan Behan, but the food today is typical pub fare––burgers, sandwiches, chicken wings. There are 18 beers and commemorative cocktails like the Dylan Thomas made with “Jack Daniels Double Neat Water Shot Back.”

Minetta

Tavern (113 MacDougal Street),

opened in 1937, counted

Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound among its

guests, and, under the ownership of

restaurateur Keith McNally, is considered one

of the city’s best steakhouses and a place not

easy to get into. Wait until 9:00 and you'll

have a better chance.

Minetta

Tavern (113 MacDougal Street),

opened in 1937, counted

Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound among its

guests, and, under the ownership of

restaurateur Keith McNally, is considered one

of the city’s best steakhouses and a place not

easy to get into. Wait until 9:00 and you'll

have a better chance.

Since 1918 Monte’s Tavern (97

MacDougal Street) has been an example of

how Italian immigrants, in this case Louis and

Sylvia Medica, thrived in the burgeoning food

business, and today Chef Pietro preserves that

legacy with lusty dishes of sausage and

peppers, lasagna, chicken Marsala and scampi

marinara in an Old World atmosphere that never dates.

atmosphere that never dates.

When lists of the best pizzerias in New

York are compiled, John’s of Bleecker

Street (278 Bleecker Street),

opened in 1929, never

fails to come in at or near the top. There are

dozens of varieties from the classics like the

Margarita to the

signature

“Boom Pie” with mozzarella,

tomato

sauce, roasted tomatoes, ricotta, garlic and

Fresh Basil. The scuffed-up décor has never

changed and the wooden booths are engraved

with decades of fans’ names.

Caffe

Reggio (119 MacDougal Street)

claims to be the first restaurant in New

York to serve cappuccino from a magnificently

noisy espresso

machine but its pastas like penne Genovese

and penne campagnola are very good and

its panino sandwiches the best in the

neighborhood.

Caffe

Reggio (119 MacDougal Street)

claims to be the first restaurant in New

York to serve cappuccino from a magnificently

noisy espresso

machine but its pastas like penne Genovese

and penne campagnola are very good and

its panino sandwiches the best in the

neighborhood.

The

Waverly Inn (16 Bank Street) in

the leafy west village dates to the mid-1800s

when it had a reputation for ghostly

visitations. Since 2006 it’s been owned by

former Vanity Fair editor-in-chief Graydon

Carter and it has long drawn a celebrity

crowd, including Taylor Swift and Bette

Midler, less crowded now than before, who come

for the signature chicken pot pie, Jonah crab

cakes and truffle mac & cheese. The

front room (below) is preferred but

it's ultra-noisy while the rear room is a bit

more civilized and has better lighting.

THE BISON

By John Mariani

David’s reluctance to

call FBI agent Frank English dated to an

incident when he’d withheld important

information from David about an earlier

investigation with Katie. David realized

English, with whom he’d previously had a good

professional relationship, was in no way

required to help an ex-NYPD cop with any

information, whether or not it was of a

secretive nature. Nevertheless, English had

given David some leads or names in his

subsequent investigations. David just didn’t

want to go to the trough if he didn’t need to.

In the case of Jeffrey Epstein, he did. He

took a deep breath and dialed English’s

number.

“Frank English, FBI, how can I help

you?”

“Frank, it’s David Greco.”

There was a pause—the agent

obviously hit a record button—then, “Whaddaya

want, David?”

“I’m

calling only because Terry Rush said you might

help with something I’m looking into in Palm

Beach. The Jeffrey Epstein investigation.”

Another

pause. “Yeah, Terry said you might call.”

“Terry

said the FBI has been keeping an eye on

Epstein for a while and you might fill me in.”

David

heard English sigh.

“This

another one of your jaunts with your

girlfriend, David?”

“Her

name’s Katie Cavuto, Frank, as you well know,

and she’s won a lot of prizes for articles

that contained info federal investigators

subsequently used in their own

less-than-productive research.” David realized

he shouldn’t antagonize the agent.

“Then have

her call me. I don’t owe you anything,

David, unless you’ve put a badge back on your

shirt and work for a legitimate police

organization.”

“Okay,

consider me a citizen calling the FBI under

the Freedom of Information Act to ask for some

info.”

“You’re

not going to get anything out of an on-going

investigation, David. You know that.”

“Frank,

if you can’t help, that’s fine; if you don’t

want to help, I get it. How about just telling

me two things?”

“Go

ahead.”

“First,

is it true you’ve got a file open on Epstein,

and second, does it have to do with the sexual

exploitation case the Palm Beach police are

looking at.”

“Yes and

yes. How’s that?”

“So, I’m going to assume

you’re looking at Epstein as a possible

kidnapper of young girls as well as at his

financial dealings.”

“Assume

away. I’m just not going to talk about it,

David. But I’ll throw you a line: You might

get more out of the DOJ or the IRS. I can tell

you they are definitely looking at Epstein and

a lot of his associates. Call these two guys:

Al Barber at DOJ and Anthony Cherico at the

IRS.”

“You

have their direct lines?”

English

said, “Do a little legwork on your own,

David,” and hung up.

David

smiled, thinking he’d actually gotten more out

of English than he’d anticipated.

Katie could

never get herself to go to an airport in

winter wearing clothes for the kind of warm

weather she expected in Palm Beach, so she

wore jeans, t-shirt, a cardigan sweater and

loafers on the plane, with enough summer

clothes for three days. As soon as she got to

Palm Beach airport she stuffed the cardigan in

her carry-on. David had already made a

reservation for her at his hotel, and, after

driving back from Miami, he was waiting for

her after getting through baggage claim.

Katie could

never get herself to go to an airport in

winter wearing clothes for the kind of warm

weather she expected in Palm Beach, so she

wore jeans, t-shirt, a cardigan sweater and

loafers on the plane, with enough summer

clothes for three days. As soon as she got to

Palm Beach airport she stuffed the cardigan in

her carry-on. David had already made a

reservation for her at his hotel, and, after

driving back from Miami, he was waiting for

her after getting through baggage claim.

“You don’t look ready for the beach,”

he said. “How about lunch?”

“I’m starving. What’s that Cuban place

you mentioned?”

David hailed a cab and they drove to

Havana Restaurant. He ordered arroz con

pollo, she ordered a Cubano

sandwich with ham, pork, cheese and pickles.

“How about a caipirinha?” asked David.

“You’re drinking caipiriñhas now

in the middle of the day?”

“I may start. Ramona Sanchez dutifully

drinks one every afternoon.”

“So how was Madam Sanchez?”

“I guess the word is ‘colorful.’ Very

smart, business savvy, at least the business

of running a call girl operation. And she

knows just about everyone in Miami, at least

the men.”

The

caipirhiñas arrived. David filled Katie in on

all she’d told him and also the little that

Frank English allowed.

The

caipirhiñas arrived. David filled Katie in on

all she’d told him and also the little that

Frank English allowed.

“So, I’m glad you’re here, Katie. I can

only get so far with an ongoing investigation

down here. As a reporter you can get to more

people.”

“Well, remember, David, I’m not on a

real assignment, though I guess I can say I’m

working on a story, which is true, even if

it’s my idea. So, who you got?”

David gave her the names and numbers of

Al Barber and Anthony Cherico.

“I already put in a call to their

offices, said you were coming down. My cop

friend Terry Rush knows them and said he could

probably arrange it so I can tag along with

you.”

While waiting for their food, Katie

called the numbers on her cell phone and left

messages. By the time they’d finished their

meal Barber at DOJ called and asked if she

could come over that afternoon because he was

leaving for a long weekend. Minutes later

Cherico called and said he could meet her at

four-thirty.

“We’d better get a move on,” said

Katie, asking for the check.

“So,” said David, “another caipiriñha?”

“I think I need a couple of café

Cubanos instead. Maybe before dinner.”

Which was

more than okay with David.

Federal

Attorney Al Barber’s office on West Flagler

Drive in West Palm Beach was an angular glass

and steel building set on a dismal-looking

part of the lagoon. Katie and David

identified themselves and were brought to a

nondescript office with a dark brown

desk, three

chairs, an American flag and a photo of

President George W. Bush.

“Heard a lot about you

two,” said Barber, who was rotund and bald,

with a salt-and-pepper goatee. He wore slacks,

a white button down shirt and foulard silk

tie. “Especially you, Ms. Cavuto. You’ve had

some tales to tell. And did so well. And

you’re David, who has been along on Ms.

Cavuto’s adventures?”

Both Katie and David thought the

comments were flippant, but Barber seemed

affable enough, offered them chairs and said,

“So how can I help you? You’re looking into

Jeremy Epstein? What exactly interests you in

him?”

Katie took the lead. “I interviewed

Epstein in New York when he was in the auction

for New York Magazine, but I was not

able to speak to him about the charges the

Palm Beach Police seem close to filing.”

“Not just them. Epstein’s got us, the

FBI and the IRS after him.”

“And what aspect are you looking into,

Mr. Barber?”

“Off the record I can say we’re

interested in his financial dealings, his

off-shore accounts, his bank transfers. Not as

sexy as snooping on his well-known orgies, but

maybe more serious for him in the end. What I

can tell you, because it’s been in the

news, is that Epstein has an uncanny ability

to pry money out of a lot of powerful people,

and many of those people attend his parties.

How he

obtained his money to buy his place here, his

New York mansion, his Caribbean island and his

ranch—he’s also got a yacht, registered in the

Cayman Islands—is a mystery to everyone, but

they don’t want to talk about it. We do, and

if it’s tied up with the sexual shenanigans,

we’ll want to know that, too. The

FBI’s looking into trafficking, the IRS is

doing what they do with tax fraud. The guy’s

getting it from all sides.”

How he

obtained his money to buy his place here, his

New York mansion, his Caribbean island and his

ranch—he’s also got a yacht, registered in the

Cayman Islands—is a mystery to everyone, but

they don’t want to talk about it. We do, and

if it’s tied up with the sexual shenanigans,

we’ll want to know that, too. The

FBI’s looking into trafficking, the IRS is

doing what they do with tax fraud. The guy’s

getting it from all sides.”

“But so far he hasn’t spent a day in

prison,” said David.

“Not yet.”

“We were also told that the local

police chief Michael Reiter has been

complaining that the state

prosecutor, Barry Krischer has been dragging

his feet, even putting up roadblocks to the

investigation.”

“That’s what brought the FBI in, and

the word is Epstein made both some promises of

paying off people and even threatened one or

two through some dirty cops. Epstein

has always paid some of them off. Krischer

is a good prosecutor when he wants to be and

when it’s politically expedient to advance his

career. He wants to be Florida’s Rudy Giuliani

(below) and start

off by getting to be mayor of Palm Beach.”

David winced.

“What,” said Barber, “you’re not a fan

of Rudy? I worked with him on some mutual

cases.”

“So did I, and as a prosecutor he was

tough on the mob, but he became like this guy

Krischer so he could run for mayor as a

crusader against crime.”

“That sounds like the Giuliani I know.

Krischer’s a bird of the same feather, and I

don’t think he wants to ruffle Epstein’s

because the creep is too well connected.

Christ, he pals around with everyone from Bill

Gates to George Stephanopoulos.”

“How about with the mobs?” asked Katie.

“Maybe just to keep things quiet, but

he likes to think of himself as this

high-class party giver and everyone owes him a

favor.”

“Do you know if Krischer ever attended

an Epstein party?”

Barber shook his head. “I doubt Barry’d

be that dumb, but then again, if he had, maybe

that’s why he’s dragging his feet on the case,

as you say.”

“We’re going to see an agent named

Cherico at the IRS after we leave here,” said

Katie.

Barber shook his head again, got up

from his desk and picked his jacket from a

hanger on a coat rack. “Don’t’ waste your

time. You won’t get piss out of Cherico. He’s

very much Mr. Clean and very much tight-lipped

about cases under investigation.”

“The why do you think he agreed so

readily to see Katie?”

“I don’t know, maybe as a favor to

Terry Rush or Reiter to see if he’ll loosen

up. If something gets into the news, Krischer

may think he has to do more than he’s doing.

But, listen, hope I’ve helped. I gotta go, got

a date to go fishing this weekend. I kind of

wish it were on Epstein’s yacht, but I haven’t

gotten an invitation. Hey, say hello to Tony

for me, will you?”

Barber walked the couple out, spoke to

the receptionist and left by a side door.

“So you think we should bother with

Cherico?” asked Katie.

“I would never break a date with an IRS

agent,” said David. “They don’t like that.”

“Hm, well, I’m sure we can pry

something out of him. Maybe give us more of a

connection with the FBI investigation. After

all, J. Edgar Hoover sent the IRS after Al

Capone on tax evasion after all else failed.

And Frank English did give us his name

specifically.”

“I think we should go, see what he’s

got to say, but I kind of think he would not

want me in on the discussion. Might spook

him.”

Katie agreed. They got a

taxi and Katie got out at the IRS offices on

North Flagler Boulevard while David went back

to the hotel.

© John Mariani, 2024

❖❖❖

MERLOT PIONEER, DIES AT 87

By John Mariani

Dan

Duckhorn, one of America’s most influential

winemakers, died on February 25 from heart

failure at the age of 87. With his then-wife

Margaret and eight co-investors, he was the first

champion of Merlot at his Duckhorn Wine

Company at a time in 1976 when few aficionados of

California’s Napa Valley wines showed much regard

for the grape variety Merlot, preferring instead the

blockbuster Cabernet Sauvignons that were hyped in

the media and wine competitions.

Merlot

was thought of as a grape to blend with Cabernet to

give it a smoothness, as had been done for centuries

in Bordeaux. After touring French vineyards, the

Duckhorns believed they could make 100% Merlots as

good as some of the great estates wines of

Saint-Émilion and Pomerol.

Merlot

was thought of as a grape to blend with Cabernet to

give it a smoothness, as had been done for centuries

in Bordeaux. After touring French vineyards, the

Duckhorns believed they could make 100% Merlots as

good as some of the great estates wines of

Saint-Émilion and Pomerol.

"I liked the softness, the

seductiveness, the color," he explained. "the fact

that it went with a lot of different foods; it

wasn't so bold, didn't need to age so long, and it

had this velvety texture to it. It seemed to me to

be a wonderful wine to just enjoy. I became

enchanted with Merlot."

Margaret, winemaker Tom Rinaldi and Dan Duckhorn,

1978

Their first harvest was in 1978,

consisting

of 1,600 cases in two bottlings—800 Three Palms

Vineyard Merlot and 800 Cabernet Sauvignon. “It was

a great year,” he said. “We could have made wine out

of walnuts

In 1988, Dan began

to acquire estates that would guarantee a continuous

supply of premium grapes, by which time the wine

writer for the New York Times pronounced him “Mr.

Merlot.”

Margaret Duckhorn (right),

who died in 2022, was known for her deep commitment

to the Napa Valley  wine industry

and was a generous philanthropist.

wine industry

and was a generous philanthropist.

A native California, Duckhorn an

earned his B.A. and M.A. in business administration

in 1962 from the University of California at

Berkeley. Afterwards he was in management for Matson

Navigation Company, Adpac Computing Languages

Company, and Crocker Associates in Salem, Oregon,

before returning to Napa Valley in 1971 to become

president of Vineyard Consulting Corporation. His

research on clones and rootstocks helped everyone

produce better fruit, and for his eminence among his

colleagues he would be ranked with giants like

Robert Mondavi, Mike Grgich and Warren Winarski.

I

remember my first taste of Duckhorn Merlots in the

early 1980s and was amazed at the richness and

complexity of this single varietal wine that did not

manifest the tannins and high alcohol of the

so-called “monster Cabs.” The Merlots were indeed

velvety and easy to match with so many foods, and

Duckhorn’s wines had a real impact on the

grape’s acceptance, not only in California, Oregon

and Washington,

but Italy, Chile, Argentina and Australia.

I

remember my first taste of Duckhorn Merlots in the

early 1980s and was amazed at the richness and

complexity of this single varietal wine that did not

manifest the tannins and high alcohol of the

so-called “monster Cabs.” The Merlots were indeed

velvety and easy to match with so many foods, and

Duckhorn’s wines had a real impact on the

grape’s acceptance, not only in California, Oregon

and Washington,

but Italy, Chile, Argentina and Australia.

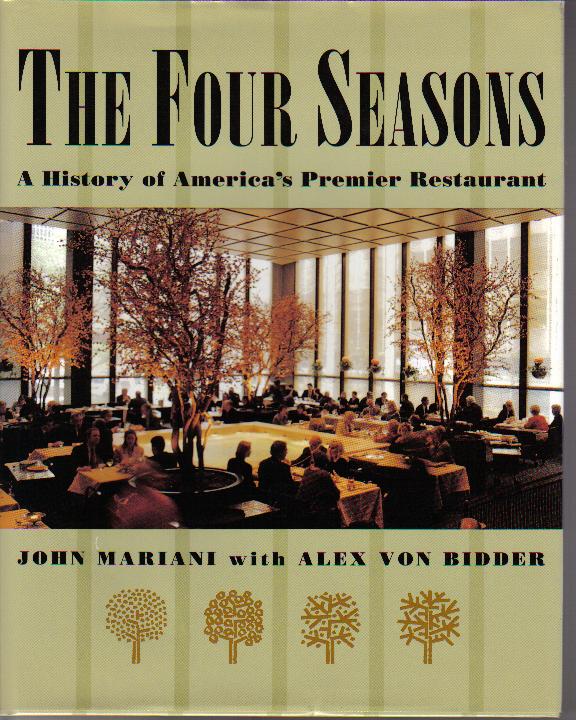

I also recall an all-Duckhorn

evening in the 1980s held at New York’s Four Seasons

restaurant, which had long championed California

wines since 1976 at annual wine dinners. The Merlots

showed splendidly from various vintages and estates,

proving that this once neglected varietal was, after

Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon, as versatile and

delicious as any made in the U.S.

In 2007, Duckhorn sold a

controlling interest of his company to GI Partners,

a private equity firm based in the San Francisco Bay

Area, and left day-to-day operations while still

involved as chairman

of the board. Then in

2016 was bought by another equity company,

TSG Consumer Partners and in 2021 went public. In

2024, it was acquired by Butter Fly Equity in Los

Angeles in an all-cash transaction valued at

approximately $1.95 billion. The company’s current

output is 800,00 cases annually, which includes

labels like Decoy, Goldeneye, Paraduxx, Migration

and Canvasback.

In

addition to his second wife, Nancy Andrus Duckhorn,

Duckhorn is survived by his three children, John

Duckhorn, David Duckhorn and Kellie Duckhorn; a

stepdaughter, Nicole Andrus; nine grandchildren; and

two siblings.

❖❖❖

THOSE WACKY POSH PEOPLE!

"Another private chef witnessed a client remodel an entire garden for an alfresco dinner party, spending £5,000 on lavender plants. Someone else had fruit flown in by private jet because “it tasted different in Spain”. Another insisted on meals “in tune with the movements of the moon”: foie gras for pets. fasting on a waning crescent; feasting on a full moon; timing her meals to 'align' with lunar energy. One sent lunch back seven times; another had a party with models, naked except for blobs of mayo."––Jack Burke, "Confessions of a private chef," Times (11/25)

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher

Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish.

Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2026