MARIANI’SVirtual Gourmet

May 20,

20012

NEWSLETTER

❖❖❖

ANNOUNCEMENT

ANNOUNCEMENT

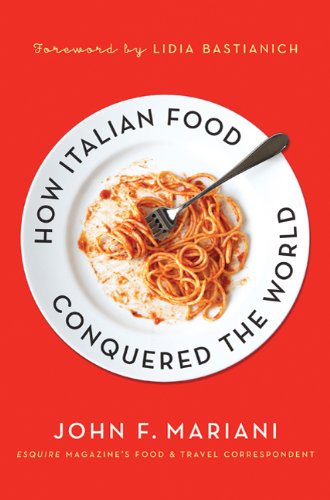

On Monday, May 21, John Mariani will be appear

as part of a Celebrity Author Wine

Dinner Series at Davio's Philadelphia (left),

111 South 17th Street, to talk about his book

How Italian

Food Conquered the World.

The wine dinner series will feature wine

pairings presented by Davio’s Sommelier Kevin

McCann and will feature a menu by Executive

Chef David Boyle. Each guest will leave with a

signed copy of the author’s book as part of

the $85.00 per person (tax and gratuity not

included). Call 215-563-4810.

When Did Tipping Become a Shakedown?

by John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

WONG

by John

Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

THAN MOST WOULD EXPECT

by Brian A. Freedman

When Did Tipping Become a Stick-Up?

by John Mariani

He then went on to detail exactly what amounts achieved precisely which results at his restaurants: "Twenty dollars will get you noticed," he said. "Fifty will get you a good table. But you're going to have to pay out a hundred to get a great table."

After 35 years of

covering restaurants around the world, I am

not naive about how greasing the palm of a

maître d' can work inane little miracles for

those who measure their own self worth by what they

perceive to be an "A" table. But upon hearing this

restaurateur's blatant statement of just how much

the bribes would cost shocked me for its arrant

smugness, this in a business supposedly built on

service and hospitality. It was the kind of

statement that defines the cynic as precisely as did

Oscar Wilde--"a person who knows the price of

everything and the value of nothing." Or, as Bob

Dylan observed, "Money doesn't talk, it screams."

After 35 years of

covering restaurants around the world, I am

not naive about how greasing the palm of a

maître d' can work inane little miracles for

those who measure their own self worth by what they

perceive to be an "A" table. But upon hearing this

restaurateur's blatant statement of just how much

the bribes would cost shocked me for its arrant

smugness, this in a business supposedly built on

service and hospitality. It was the kind of

statement that defines the cynic as precisely as did

Oscar Wilde--"a person who knows the price of

everything and the value of nothing." Or, as Bob

Dylan observed, "Money doesn't talk, it screams."If restaurateur extraordinaire Danny Meyer (below) has taught his colleagues anything (read his book Setting the Table), the relationship between the guest and staff should be warm, indeed, fun, for all concerned, and demanding--not anticipating--a twenty, fifty or c-note in a maître d's hand for a table is the exact opposite of all that. By the same token, if a guest has a delightful evening and the maître d' helped make it so, then a tip as the guest exits is perfectly hospitable on both ends, especially if that guest intends to be a regular. The fact is that, not only at Danny Meyer's restaurants but any restaurant that uses Open Table can easily gather summations of guest's likes and dislikes, and, along with notes taken by the restaurant staff, a profile can be compiled so that the next time he or she visits, the guest will be enchanted to find the staff caters specifically to his likes and dislikes. That is what hospitality is all about, not bribery. And those who frequent a restaurants, as with any other establishment, are going to get preferential

treatment simply as a matter of

valuing their fidelity. Celebrities, sports figures,

politicians, and restaurant critics, in that order,

get good tables as a matter of course; the most

fawned over of all? Police commissioners and

precinct captains, who need not pay off for the

courtesy. (By the way, the term Siberia,

indicating a table is a less-than-appealing part of

a restaurant, was coined by actress Peggy Hopkins

Joyce [below]

in 1931 at NYC's El Morocco supper club when she was

inadvertently shown to a lesser table.)

treatment simply as a matter of

valuing their fidelity. Celebrities, sports figures,

politicians, and restaurant critics, in that order,

get good tables as a matter of course; the most

fawned over of all? Police commissioners and

precinct captains, who need not pay off for the

courtesy. (By the way, the term Siberia,

indicating a table is a less-than-appealing part of

a restaurant, was coined by actress Peggy Hopkins

Joyce [below]

in 1931 at NYC's El Morocco supper club when she was

inadvertently shown to a lesser table.) Of course, people who love to be seen

throwing money around are the same people who feel

abject ego-deflation if they had to play by the

normal rules of hospitality. I was told that

the late plumbing contractor John Gotti, who ended

up getting his meals through a slot in solitary

confinement, used to tip the amount of the

bill itself, always insuring him of first-rate

service. (The fact that he was a vengeful gangster

might have had something to do with it.)

Of course, people who love to be seen

throwing money around are the same people who feel

abject ego-deflation if they had to play by the

normal rules of hospitality. I was told that

the late plumbing contractor John Gotti, who ended

up getting his meals through a slot in solitary

confinement, used to tip the amount of the

bill itself, always insuring him of first-rate

service. (The fact that he was a vengeful gangster

might have had something to do with it.)Tipping, at least in Anglo-American society is very old, dating back in print to 1755. The first specific reference to a waiter receiving a tip was in 1825. Since then it has become common practice in Great Britain and the U.S., although until recently it was considered very bad form for a bartender in a pub to take a tip. In the first half of the last century, that is, the 20th, fifteen percent of the bill, before taxes, was the norm; of course, back then--say up until the 1980s--few people ever ordered expensive wines, so the idea of tipping fifteen percent on beverages was ridiculous. Sommeliers would receive a five or ten percent tip, but only if they did somewhat more work than merely open a bottle. There was also a time, almost wholly gone, when captains and waiters in posh restaurants were tipped separately, five and fifteen percent, respectively, with two slots on credit cards for that purpose, which was a real pain in the neck. The tips were usually pooled anyway, with busboys and bartenders getting a cut. Maître d's were given money on the way out. (By the way, it is a myth that the word "tip" is short for "to insure promptness.")

Of course, all this is, obviated by the inclusion on the bill of a service charge, increasingly the case in Great Britain, for the reason that their European guests all too often pretend not to know about tipping on the bill because in places like France and Italy, the service charge ("service compris," "servizio incluso") was part of the cost of the food itself; that is, if a lamb chop cost $25, about 10 to 12 percent of that cost was for service. The so-called pour boire ("for a drink," below) was no more than a few francs (before euros) one left on the table, perhaps rounding off the bill. This was pretty much the case in Europe until the 1960s

when Americans en masse

began traveling to France, Spain, Italy, and Greece,

and, either ignorant of the included service charge

or not wanting to seem cheap, added the usual 15

percent tip they would have back in the States--on

top of the included service charge.

when Americans en masse

began traveling to France, Spain, Italy, and Greece,

and, either ignorant of the included service charge

or not wanting to seem cheap, added the usual 15

percent tip they would have back in the States--on

top of the included service charge. The expansion of this to just about every staffer in hotels also grew, despite the fact that a service charge is built into the price of the room by law. So Americans would tip everyone in sight until it became routine. I recall many years ago, when informed that Americas were tipping the chambermaids in France (who would be sharing in the service charge), the French travel and food guide editor Christian Millau gasped, "You mean after I pay $500 for a room I have to pay more to have it cleaned?" So now in Europe tipping has become far more common, even expected, despite a note that it's included printed on the menu or bill; if it is not, you should ask.

The tinny age of tipping was in the post-war period when maître d's and captains at French restaurants in Paris, London and Rome could wither an incoming guest with a glance that meant, "You are obviously a nobody, but I might be convinced to seat you if you pay me a wad of money." Even then it didn't always work: the imperious owner and host Henri Soulé of the famous Le Pavillon in NYC refused ever to give a good table to his despised landlord, who happened to be Harry Cohn, head of Columbia Pictures. Cohn threatened to evict Le Pavillon, but Soulé refused to budge and was out the door. (Le Pavillon relocated.)

More distressing was the upward spiral

of tipping from the normal fifteen percent to twenty

percent--previously reserved for exceptional service

beyond the usual call of duty. Today, twenty percent

has become the standard, while twenty-five is now

the larger reward. Of course, the show-offs

will tip whatever they think will make the waiter or

captain love them. Don't misunderstand: were I

one of the one-percenters on earnings, a public

figure like Jay-Z, or a Russian billionaire, I would

tip very, very generously too, but these days people

feel intimidated if they don't tip at least twenty

percent, even on wine. Then again, as a

restaurateur once told me, "If a guy can afford a

$500 bottle of wine, he can readily afford to tip 20

percent on it too."

More distressing was the upward spiral

of tipping from the normal fifteen percent to twenty

percent--previously reserved for exceptional service

beyond the usual call of duty. Today, twenty percent

has become the standard, while twenty-five is now

the larger reward. Of course, the show-offs

will tip whatever they think will make the waiter or

captain love them. Don't misunderstand: were I

one of the one-percenters on earnings, a public

figure like Jay-Z, or a Russian billionaire, I would

tip very, very generously too, but these days people

feel intimidated if they don't tip at least twenty

percent, even on wine. Then again, as a

restaurateur once told me, "If a guy can afford a

$500 bottle of wine, he can readily afford to tip 20

percent on it too."So, depending on your spirit of generosity, bank account, or genuine gratefulness, tip what you want; also, do not tip when service has been terrible. I know this makes Americans terrified that the waiter will run after you in the street or spike your coffee with something unpleasant, but registering your discontent with the maître d' or owner is at the end of the day helpful to the management, as long as your complaints are legitimate and delivered courteously.

There are still places in the world that frown on tipping as uncivilized and dishonorable--Japan being a paramount example of a country that believes a service person should be paid what he is worth by an employer, not by a guest in his restaurant. And that's more or less the case when service is included in a bill. Tipping is almost always awkward, and now it seems always expected. What was once a congenial gesture has now become a requisite, especially when the restaurateur lays out the fees in advance just to get noticed.

❖❖❖

NEW

YORK CORNER

by

John Mariani

WONG

7

Cornelia Street (near Bleecker Street)

212-989-3399

www.wongnewyork.com

I do not

mean to damn Wong with faint praise by saying that it

is yet another Asian-style eatery in the West Village

that could as easily be in Brooklyn or Astoria,

meaning that there are so many delightful places all

over NYC serving savory, spicy food along Wong's

lines. With those other places, Wong shares a

storefront ambiance, not much décor, an open

kitchen manned by two or three cooks, t-shirted

waiters indistinguishable from the busboys, and a

decibel level that makes conversation impossible

without yelling across the table.

I do not

mean to damn Wong with faint praise by saying that it

is yet another Asian-style eatery in the West Village

that could as easily be in Brooklyn or Astoria,

meaning that there are so many delightful places all

over NYC serving savory, spicy food along Wong's

lines. With those other places, Wong shares a

storefront ambiance, not much décor, an open

kitchen manned by two or three cooks, t-shirted

waiters indistinguishable from the busboys, and a

decibel level that makes conversation impossible

without yelling across the table.

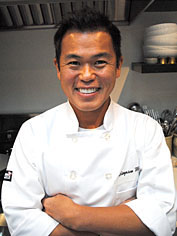

Chef/owner Simpson Wong (below), who also

runs Café Asean, is well regarded and well

liked in the food community, and I doubt he feels he's

re-inventing cuisine in this modest new place.

He has, however, trotted out the hackneyed terms

"locavore" and "sustainability" to describe it.

As Chef Fergus Henderson of London's St. John

restaurant said recently, "Every chef now states that

their dishes are seasonal and local. This makes

one wonder: what were they cooking before? Food not in

season and from very far

away?" The word "locavore" has become as meaningless

as putting "fresh" next to every ingredient.

season and from very far

away?" The word "locavore" has become as meaningless

as putting "fresh" next to every ingredient.

To be sure, many dishes on Wong's

menu you're not likely to find easily elsewhere, and

many of them are delicious. The menu is small:

four starters, four main courses, with nightly and

market specials, a "Typhoon lobster" dinner ($36 per

person) and "Duckavore dinner" ($65) for the entire

table, and two desserts. There are some items as

ubiquitous around town as a flat iron steak with

fingerlings and ramps, here touched by coriander, and

I thoroughly enjoyed a crispy soft shell crab with

roasted radish, brown butter, soy, and curry leaves.

Shrimp fritters with ham, rice

sheet, Asian pear and sunflower sprouts was all right,

the ingredients not much helping each other, and

scallops did not gain much from crispy duck tongue,

cucumber and jellyfish except some texture. The biggest wow at

Wong is Hakka pork belly, as luscious and sensually

fatty as any I've ever had, with hakurei turnip,

taro tater tots, and calamansi. Also terrific were

what are called "duck buns" on the menu, which doesn't

begin to describe what is more like a duck hamburger

with a bun that is almost better than its contents of

juicy, sweet braised duck leg, with Chinese celery and

cucumber. This alone I would go back for--in a bag, if they did

take-out.

The biggest wow at

Wong is Hakka pork belly, as luscious and sensually

fatty as any I've ever had, with hakurei turnip,

taro tater tots, and calamansi. Also terrific were

what are called "duck buns" on the menu, which doesn't

begin to describe what is more like a duck hamburger

with a bun that is almost better than its contents of

juicy, sweet braised duck leg, with Chinese celery and

cucumber. This alone I would go back for--in a bag, if they did

take-out.

Of the main dishes the lobster egg

foo young (below)

has been much praised by others, but it's a pretty

small lobster, with leeks, salted egg yolks, and a

dried shrimp crumble that is tasty but not earth

moving. Wood-grilled chicken with chrysanthemum greens

and jicama was fine, while two rice and noodle

dishes--cha cha la

wong hake with turmeric, dill and rice

noodles, and a dish of rice noodles with pork, cucumber, fried egg and

something called, for reasons that escape me,

"shiitake bolognese."

cucumber, fried egg and

something called, for reasons that escape me,

"shiitake bolognese."

Judy Chen's desserts read well but

don't amount to much: "Duck à la plum" was

actually roast duck-flavored with star anise poached

plums, tuile and five-spice cookie, but no one at our

table of four picked up any duck flavor at all.

Lemon shortcake with lemon curd, butter cake, and sour

cream topping was fine, but seemed an afterthought.

The service staff at Wong is not

among NYC's finest. On our calling to tell the

restaurant we'd be a few minutes late, whoever picked

up the phone couldn't find our reservation name (which

was made under a friend's), then handed the phone to

someone else, who found it quickly. Requests for

tablespoons for four different dishes brought one

spoon to the table. The interior, with no soft

surfaces to tamp down the noise, is made from salvaged

wood, the chairs inspired by those you sat in in

grammar school. There's a bar and counter

to eat and drink at.

So, if you're in the

neighborhood and can drop in, Wong will serve up some

good and unusual food. That's about it.

Wong

is open for dinner

Mon.-Sat. Starters $9.50-$16, main courses

$18-$26.

❖❖❖

THAN MOST WOULD EXPECT

by Brian A. Freedman

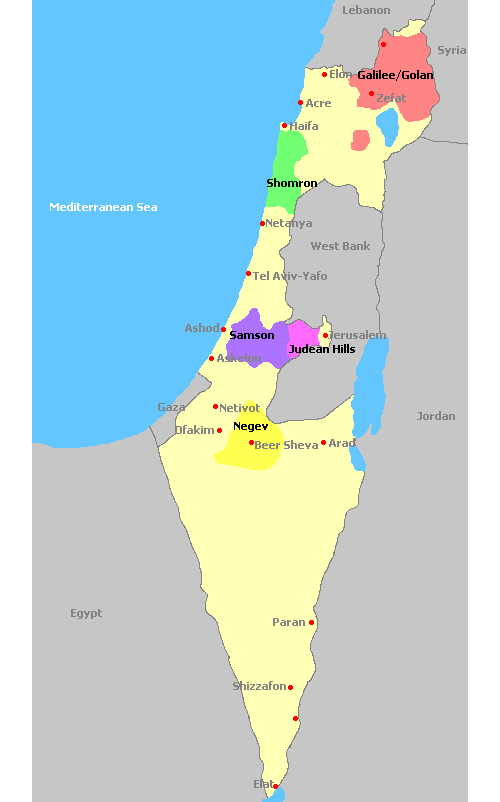

The irony of this is twofold. First, of course, that the sickly-sweet liquid embodiment of Passover and Shabbat is produced in Naples, NY, not Israel. Second, Israel is home to a wine industry as varied, complex, and ambitious as you’re likely to encounter anywhere in the world. And yet, too many people don’t give it the credit it so richly deserves.

Much

of the problem is with the popular conflation of Israeli

wine, kosher wine, and the notorious mevushal

wine--a mistake too many people still make, and that,

perhaps even before they taste a particular Israeli

wine, colors their experience--and not necessarily for

the positive. I must admit

that, over the course of a week-long tasting trip to

Israel I took this winter, I found my own preconceived

notions of those three distinctions challenged and, more

often than not, completely changed.

Much

of the problem is with the popular conflation of Israeli

wine, kosher wine, and the notorious mevushal

wine--a mistake too many people still make, and that,

perhaps even before they taste a particular Israeli

wine, colors their experience--and not necessarily for

the positive. I must admit

that, over the course of a week-long tasting trip to

Israel I took this winter, I found my own preconceived

notions of those three distinctions challenged and, more

often than not, completely changed.To begin, then, not all Israeli wine is certified kosher, though the vast vast majority of it is. This is for economic reasons as much as anything else. As I noted in my previous article on the changing food trends in Israel, the options for non-kosher eating abound. Why, then, would a young Tel Aviv resident feel guilty about drinking non-kosher wine with his plate of jamon Iberico?

The economics of wine sales in Israel, however, seem to tie kosher-certified wine with the opportunity for economic success. Most grocery stores, after all, will only sell kosher products. As a result, wine producers have a distinct incentive to attain certification in order to expand their sales base. Israelis have come to understand that kosher wine and quality wine are not mutually exclusive. In fact, the requirements for kosher certification share a remarkably similar philosophical grounding to those for organic certification in America and Europe. This makes sense, even on a linguistic level: etymologically, kosher means "pure," and many kashrut wine-production laws generally reflect millennia of received grape-growing, wine-producing wisdom and common sense. Newly planted vines, for example, cannot be harvested for kosher wine until their fourth year. (Most wine experts will tell you that too-young vines don’t produce grapes that lead to interesting wines anyway.) And the cleanliness required by kashrut law results in a serious sense of attention to detail in kosher wineries, which is always good winemaking practice regardless of religious edict.

Other aspects of the laws governing kosher wine are more symbolic and have little appreciable impact on the sensory appreciation of the liquid itself. Certainly the fact that only Sabbath-observant Jews can handle the wine and equipment or that a fallow season every seventh year is required (there are loopholes for this), don’t in any way detract from the wine. An expert winemaker, regardless of his level of personal religious observance, oversees it all anyway.

The problem is with what most of us in America are familiar with--Mevushal wine, or wine that has been flash pasteurized at 180-degrees F and then quickly cooled down, thus allowing Orthodox Jews to consume it even if it’s been handled or poured by non-Jews. Various studies have shown that discerning the difference between mevushal and non-mevushal wine is difficult, but, personally, I can generally tell the difference, and vastly prefer non-mevushal wine. This, of course, is common sense, and an opinion likely shared by most wine professionals--even the vast majority to whom I spoke in Israel. The consensus seemed to be that serious winemaking and mevushal were, if not at loggerheads, then at least incompatible in the general sense.

The point is this: Kosher, non-mevushal wine from Israel suffers no inherent defects or drawbacks, either on its own or in the context of any other quality wine from anywhere in the world. Too bad it’s still often relegated to the “kosher” section of most American wine shops, which seems to short-change it by focusing on this single aspect of its identity.

Over the course of my time in Israel this past winter, it became deliciously clear that the country is home to a wine industry more interesting, soulful, and diverse than many people still believe. Indeed, so many of the wines on their own would have been excellent, even exclusive of the unusual hardships that winemakers and vineyard managers too often contend with there (the threat of war, issues of irrigation, etc.).

One of my first visits was to Galil Mountain, far enough north that I could see the border with Lebanon from the tasting room. Here, in fact, they had a front-row seat to the war with Hezbollah in 2006--and still managed to harvest their grapes successfully

Political and qualitative misconceptions notwithstanding, the wines of Israel are poised to finally make the mark they so richly deserve on the international stage. The best of them seem to be finding a fascinating middle ground between Old World terroir specificity and New World exuberance. This was most obviously on display with Syrah, which, at its best here, tends to express a sense of funkiness or earthiness in a Northern Rhône vein, as well as a deep well of fruit you might more readily often associate with certain parts of Australia. Tulip Winery’s Syrah Reserve 2009, for example, embodied this aesthetic with porcini and peppercorn dancing alongside sappy black cherry, blackberry, Kirsch, and dark chocolate, all lifted by an unexpected mint note.

Binyamina references the Northern Rhône rather explicitly in its blend for the “Ruby” 2008, part of a line of high-end wines it calls “The Chosen.” This particular one, 96% Syrah and 4% Viognier, boasts smoked game, white peppercorn, and macerated plum aromatics, and gripping flavors of cobbler, warm vanilla, dates, and spicy chocolate. Shiloh’s Shiraz “Secret Reserve” 2008, despite its 20 months in French oak, is a crackling-fresh wine, with bright berry and cherry notes, as well as spice, pomegranate, and, on the finish, a beautiful hint of licorice. I’d drink it 2014 - 2021. Recanati also takes advantage of the classic Rhône-style blend: Their Syrah-Viognier 2010 is beautifully balanced on the edge of the Old and New Worlds.

Cabernet Sauvignon also does very well in Israel. Yatir’s 2008 Cabernet (blended with 11% Shiraz), with its juxtaposition of mineral and scorched earth notes with charred sage, oregano, and sweet wild-berry compote, is both excellent now and holds the promise of evolution through 2018 or so. Artsi Winery’s 2011 Cabernet “Raphael” is dense on the tongue with chocolate and Kirsch, as well as sage, brown spice, and a pleasantly complicating grilled note. Yarden, expectedly, also produces an excellent one; the 2008 Cabernet is a chewy, minty, red-fruit explosive treat. Or Haganuz and Gvaot also produce successful, expressive bottlings, as does Binyamina, notably with its remarkable “Aquamarine.”

Unlike nearly anywhere else in the world where I’ve tasted it, Petit Verdot has the potential to be a serious contender as a varietally labeled wine here. I was, time and again, stunned and charmed by how brilliantly it does on its own, or only slightly blended. The Yatir Petit Verdot 2008 (15% Cabernet Franc) smelled of brambly fruit, spice, and cigar tobacco, and tasted of birch bark, minerals, dark fruit in a black cherry vein, concentrated pomegranate, and a bit of mocha. It’s a wine built for aging--through 2020, I think--but excellent right now with a bit of air. Barkan also had success with its Petit Verdot Reserve 2010, a barrel sample of which was already well on its way to becoming a spicy, bright example of the variety. Gat Shomron’s 2009 bottling also worked well, its spice and almost medicinal fruit calling out for grilled meats.

As in so many wine-producing countries that are really working to understand the best locations and methods for specific grape varieties, Israel is home to a robust culture of blending. Some of the best wines I tasted there are either classic or unique combinations of grapes that result in wildly exciting bottles. Yatir “Forest” 2008 takes the best characteristics of Cabernet Sauvignon (58%) and Petit Verdot (32%) and transmogrifies the combination into a wine that sings with spiced plum, fig paste, hoisin sauce, and espresso grinds on the nose and flavors of black cherry, cobbler, fig syrup, tobacco, peppercorn, and garrigue. The Shiloh “Legend” 2009 mixes Shiraz, Petit Sirah, Petit Verdot, and Merlot into an aromatically complex red with everything from flowers and sandalwood to oregano, Kirsch, and caramel. Their “Mosaic” 2007 is also a winner, that blend dominated by Merlot (50%) and filled in with Cabernet Franc (20%) Cabernet Sauvignon, Petit Verdot and Shiraz.

The Domaine Netofa “Tinto” 2010, an unexpected blend of Touriga Nacional (60%) and Tempranillo (40%), is a meaty, plummy winner, as is their Syrah-Mourvèdre 2010 with its tar, black peppercorn, and dark cherries. Barkan makes a fantastic 2009 Pinotage, and while the oak still needs some time to be absorbed, its red currant and brown spice character are appealing. Galil Mountain is also working with Barbera, and with a success that you rarely find outside Italy’s Piedmont region. I also tasted a lovely dry-farmed, bush-vine Carignan from Recanati, a luscious, unusual 2005 Port-style dessert wine from Tanya, and countless other unexpected blended or varietally-labeled bottlings that really emphasized the range of possibilities for even further success that Israeli wine possesses.

The one issue that

seemed to come up regularly, however, was pricing.

Israeli wine--the good stuff, at least--generally

doesn’t come cheap. And while the wines are more often

than not worth it, I fear that too many consumers aren’t

giving them the chance they richly deserve as a result

of this. Whichever Israeli producer first hits it big in

America with a great sub-$15 bottle will, I suspect,

lead the way in introducing a critical mass of consumers

to all that they’ve been missing.

The one issue that

seemed to come up regularly, however, was pricing.

Israeli wine--the good stuff, at least--generally

doesn’t come cheap. And while the wines are more often

than not worth it, I fear that too many consumers aren’t

giving them the chance they richly deserve as a result

of this. Whichever Israeli producer first hits it big in

America with a great sub-$15 bottle will, I suspect,

lead the way in introducing a critical mass of consumers

to all that they’ve been missing. There were some very good whites, too, though in general, I preferred the reds. Still, there’s potential in this category, and in a range of styles. Tulip Winery’s “White Tulip” 2011, an unusual blend of Gewürztraminer (70%) and Sauvignon Blanc (30%), shows the expected lychee and rose water of its dominant grape variety, but these are sliced through by the acidity and grapefruit of the SB. It’s a fascinating wine, as is the Chenin Blanc Réserve 2009 from Latour Netofa, its crackling-fresh fruit and gorgeous minerality exceptionally impressive. Recanati’s “Yasmin” 2011 brings together Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc in a green apple- and granola-inflected wine that’s drinking very well right now. Yarden’s 2010 Chardonnay from the Odem Vineyard seems to share a certain amount of expressive DNA with Meursault, its nutty, full-bodied palate complicated by unexpected flashes of mango and mandarin orange peel. Teperberg impressed me with its late-harvest Riesling “Silver” 2010, whose beautiful notes of persimmon, white-blossomed flowers, toffee, and white tea kept me going back for additional sips.

In the southern Judean Hills one day, our decidedly international group came across a young shepherd tending to his flock . Several of the Chinese members of our delegation had never seen a Middle Eastern man in person before, and, from the looks of the shepherd’s reaction, he had never come across Asian women prior to that encounter. What followed was a moment that, for me at least, embodies so much of what makes travel such a necessity: They all took photos with one another, smiling and laughing and communicating with ease, despite the total lack of a shared language.

For all the bad news we hear about this part of the world, it’s a majestic, magical place to visit, and there’s far more to gain from going there than most people realize. Its growing wine industry, I think, will play a significant role in introducing it to consumers and professionals from all over the world. There’s a sense of poetry to this: In the region where the grapevine was ostensibly domesticated, wine is still bringing people together, and deliciously so, all these thousands of years later.

❖❖❖

NEXT TIME JUST RENT A GPS

“It's not often

that I plan for my death. But I did today,

as I was heading for an isolated cliff on Inishmore,

the largest of Ireland’s Aran Islands. I was

accompanied by a stranger—a van driver I’d asked to

bring me as close as one could get on four wheels to a

Celtic monument called Black Fort. But when the road

ended in a flurry of rock and daisies, he insisted on

escorting me.”—Cristina Nehring, “Islands with

Benefits,” Condé

Nast Traveler (3/12).

HOW MANY SLICES?

HOW MANY SLICES?

Urology Associates of Cape Cod is offering free pizza

with a vasectomy.

Dr. Evangelos Geraniotis calls a vasectomy an

"easy and less stressful"

form of birth control.

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's

books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

|

My latest book, which just won the prize for best book from International Gourmand, written with Jim Heimann and Steven Heller, Menu Design in America, 1850-1985 (Taschen Books), has just appeared, with nearly 1,000 beautiful, historic, hilarious, sometimes shocking menus dating back to before the Civil War and going through the Gilded Age, the Jazz Age, the Depression, the nightclub era of the 1930s and 1940s, the Space Age era, and the age when menus were a form of advertising in innovative explosions of color and modern design. The book is a chronicle of changing tastes and mores and says as much about America as about its food and drink.

“Luxuriating vicariously in the pleasures of this book. . . you can’t help but become hungry. . .for the food of course, but also for something more: the bygone days of our country’s splendidly rich and complex past. Epicureans of both good food and artful design will do well to make it their coffee table’s main course.”—Chip Kidd, Wall Street Journal.

“[The menus] reflect the amazing craftsmanship that many restaurants applied to their bills of fare, and suggest that today’s restaurateurs could learn a lot from their predecessors.”—Rebecca Marx, The Village Voice. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square Cafe,

Gotham Bar & Grill, The Modern, and

Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las Vegas

is the new on-line site for Virtual Gourmet

contributor John A. Curtas., who since 1995

has been commenting on the Las Vegas food

scene and reviewing restaurants for Nevada

Public Radio. He is also the

restaurant critic for KLAS TV, Channel 8 in

Las Vegas, and his past reviews can be

accessed at KNPR.org.

Click on the logo below to go directly to

his site.

Eating Las Vegas

is the new on-line site for Virtual Gourmet

contributor John A. Curtas., who since 1995

has been commenting on the Las Vegas food

scene and reviewing restaurants for Nevada

Public Radio. He is also the

restaurant critic for KLAS TV, Channel 8 in

Las Vegas, and his past reviews can be

accessed at KNPR.org.

Click on the logo below to go directly to

his site.

Tennis Resorts Online: A Critical Guide to the World's Best Tennis Resorts and Tennis Camps, published by ROGER COX, who has spent more than two decades writing about tennis travel, including a 17-year stretch for Tennis magazine. He has also written for Arthur Frommer's Budget Travel, New York Magazine, Travel & Leisure, Esquire, Money, USTA Magazine, Men's Journal, and The Robb Report. He has authored two books-The World's Best Tennis Vacations (Stephen Greene Press/Viking Penguin, 1990) and The Best Places to Stay in the Rockies (Houghton Mifflin, 1992 & 1994), and the Melbourne (Australia) chapter to the Wall Street Journal Business Guide to Cities of the Pacific Rim (Fodor's Travel Guides, 1991).

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Editor/Publisher: John

Mariani.

Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani, Robert Mariani,

John A. Curtas, Edward Brivio, Mort Hochstein,

Suzanne Wright, and Brian Freedman. Contributing

Photographers: Galina Stepanoff-Dargery,

Bobby Pirillo. Technical Advisor: Gerry McLoughlin.

To un-subscribe from this newsletter,click here.

© copyright John Mariani 2012