MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

August 10,

2025

NEWSLETTER

Founded in 1996

ARCHIVE

Carole Lombard and Clark Gable at the MGM Commissary, 1936

THIS WEEK

THE VIEW FROM MOUNT OLYMPUS:

WHAT DID THE GODS EAT AND DRINK?

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

ST. URBAN

By John Mariani

HÔTEL ALLEMAGNE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

THE WINES OF MICHIGAN

By John Mariani

WHAT DID THE GODS EAT AND DRINK?

By John Mariani

Rare is the

Greek god or goddess who is not a cosmic

annoyance to human beings. They are

immeasurably flawed, vindictive, irrational,

self-serving, mean-spirited and use their

powers to outwit each other and mankind.

.jpg) They were also

gluttons: According to Homer (left),

the gods lounging atop Mount Olympus

“feasted all day until sunset and ate to

their hearts content,” then they would put

up their feet and listen to music and poetry.

They were also

gluttons: According to Homer (left),

the gods lounging atop Mount Olympus

“feasted all day until sunset and ate to

their hearts content,” then they would put

up their feet and listen to music and poetry.

Dionysus

(right) was a god the Greeks

most happily imitated. Called Bacchus by the

Romans, he was the privileged son of Zeus

himself and god of agriculture, who showed men

how to grow wine grapes and make wine; he was

also a comic

sower of decadence, though he was never

depicted as obese by Greek sculptors.

He would conduct his conquests

surrounded by a retinue of Bacchii that

included drunken satyrs and mad women known as

maenads who wore crowns of snakes and would

tear animals and enemies to pieces.

The feasts celebrating Dionysus date to

Attica, where a yearly wine festival was held

during the winter solstice and grew into

raucous, sexually charged, raunchy scenes in

which masked men dressed in goat skins, giant

phalluses were carried about and flaunted and

dances tended towards the obscene.

Drinking parties held in Dionysus’s

honor, called sympósions

(below), became very deliberate

gluttonous events, despite Dionysus’s own

dictum that a man should drink only three cups

of wine at dinner: toasting the first to

health, the second to love and pleasure and

the third to sleep, after which a guest should

go home to bed. Few paid much attention once

the party got going.

Such banquets

were all male, with the exception of naked

dancing girls, and the manners and rituals of

inviting guests, making the menus and deciding

on the entertainment were very involved.

During a sympósion guests arrived, their feet

would be washed by slaves, then they reclined

on couches; a communal cup called a psycter

(below) of aromatics was passed

around, and the eating part of the banquet

began. But the serious drinking came after

dinner.

Such banquets

were all male, with the exception of naked

dancing girls, and the manners and rituals of

inviting guests, making the menus and deciding

on the entertainment were very involved.

During a sympósion guests arrived, their feet

would be washed by slaves, then they reclined

on couches; a communal cup called a psycter

(below) of aromatics was passed

around, and the eating part of the banquet

began. But the serious drinking came after

dinner.

The meal would consist of an enormous

number of dishes. A

poem written around 400 BC called The

Banquet describes a feast well

appreciated by its enthusiastic author.

In

came a pair of slaves with a shiny table, and

another, and

another until they filled the room.

They fetched in show-white barley-rolls

baskets,

A casserole— no bigger than that—call

it a marmite, full of a

noble eel with a look of the conger

about him.

Honey-glazed shrimps besides, my love,

Squid sprinkled with sea-salt,

Baby birds in flaky pastry,

And a baked tuna, gods! What a huge one

fresh from the fire

and

the

pan and the carving knife.

Enough steaks from its tender belly to

delight us both as long

as we might care to stay and munch.

. . . . Then the same polished tables,

loaded with more good

things, sailed back to us, “second

table,” as men say

Sweet pastry shells, crispy flapjacks,

toasted sesame cakes

drenched in honey sauce,

Cheesecake, made with milk and honey,

baked like a pie;

Cheese-and-sesame sweetmeats fried in

the hottest oil in

sesame

seeds were passed around.

At that point, with

only small bites called tragemata

to nibble on, the guests began to drink as

much as they liked of wine cut two-thirds by

water. If a man protested that he’d had enough

wine and refused another cup, he had to

perform some silly entertainment, like dancing

naked or carrying the girl flute-player around

the room. Parasites was the name given to

those who arrived late to the party and

mooched off the remains. Only around 500 BC

were women invited to join the fun, but they

were largely courtesans, prostitutes and

female artists.

How such a gentle philosopher named

Epicurus became equated with the

term “epicureanism” as a license to excessive

indulgence, particularly in food and drink, is

a unfortunate because he actually advocated

“katastematic pleasure” that is experienced

through a harmonious state of mind free of

mental distress and pain achieved through a

simple life rather than by activating

unnatural pleasures like gluttony that take

hold of the mind’s free will.

In Homer’s Odyssey,

the poet

insists that while heroes need proper

nourishment, mostly meat and bread, it would

be foolhardy for them to indulge in

gluttonous behavior. Nevertheless,

in The

Iliad the hero Odysseus is called by an

opponent “wild for fame, glutton for cunning,

glutton for war,” while Odysseus uses the word

“glutton” to describe King Agamemnon as a

“dog-faced” glutton” and “people-devouring

king.”

When Odysseus sails into

the clutches of the breathtakingly beautiful

goddess Circe (left), she turns

his

men into swine with a drugged drink (she turns

them back, too) and persuades him to feast

with her and her maidens on “enough food and

drink to last forever.” And then to bed.

Odysseus and his men gave in to her seductions

and stuck around the island “day

after day, eating food in plenty, and drinking

sweet wine” for an entire year.

But the candidate for Super Glutton is

the god Herakles (Hercules to the Romans), a

bastard son of Zeus whose wife Hera tried to

abort him and afterwards tried to make his

life miserable. Herakles (below) is, of

course, a person of inhuman  strength,

but he emerges as a comic figure among Greeks

who regarded his gluttonous antics as human

foibles. From the earliest days of Greek drama

Herakles is ridiculed for his brutish way of

eating his food, his preference for a good

meal versus a good woman and, in

Aristophanes’s The Bird,

even his reluctance to leave a barbecue in

order to help save his

own father. In an earlier play, The Frogs,

Aristophanes had also portrayed Herakles as a

god led around by his nose at the thought of

food, describing how in a trip to the

underworld he had gobbled up sixteen loaves of

bread, 20 portions of beef stew, a mess of

fish and a newly made goat’s cheese—baskets

included—then, bellowing and drawing his

sword, skipped out on the bill.

strength,

but he emerges as a comic figure among Greeks

who regarded his gluttonous antics as human

foibles. From the earliest days of Greek drama

Herakles is ridiculed for his brutish way of

eating his food, his preference for a good

meal versus a good woman and, in

Aristophanes’s The Bird,

even his reluctance to leave a barbecue in

order to help save his

own father. In an earlier play, The Frogs,

Aristophanes had also portrayed Herakles as a

god led around by his nose at the thought of

food, describing how in a trip to the

underworld he had gobbled up sixteen loaves of

bread, 20 portions of beef stew, a mess of

fish and a newly made goat’s cheese—baskets

included—then, bellowing and drawing his

sword, skipped out on the bill.

Though

sometimes depicted in terracotta figurines

from the 5th and 4th

centuries BC as pot-bellied, overwhelmingly

Herakles was sculpted in marble and bronze by

both Greek and Romans as a male figure of

daunting musculature with what today are

called “killer abs.”

Though

sometimes depicted in terracotta figurines

from the 5th and 4th

centuries BC as pot-bellied, overwhelmingly

Herakles was sculpted in marble and bronze by

both Greek and Romans as a male figure of

daunting musculature with what today are

called “killer abs.”

Alexander the Great (below) was

a mere mortal and a big drinker who on “on such a day,

and sometimes two days together, slept after a

debauch.” On one occasion he held a drinking

contest with 41 contenders chosen from his

army ranks, others local citizens. Whoever

drank the most would be awarded a crown worth

a talent in gold––worth about $250,000

today. One of Alexander's soldiers,

named Promachus. won the prize after knocking

down four gallons of wine (unmixed with

water). But not everyone, especially the local

people, was used to drinking so much wine,

resulting in 41 deaths from alcohol poisoning.

Never defeated in battle, Alexander’s demise came at the age of thirty in 323 BC, in Babylon. The earliest reports say that after nights of excessive drinking, the young king fell ill with fever and died two weeks later. Others contend he was poisoned by his viceroy Antipater, while more modern conjectures propose the weary conqueror had picked up typhoid fever or meningitis or was done in by his over-use of the medicine hellebore, then prescribed as a purgative as well as for gout and signs of insanity.

NEW YORK CORNER

43 East 20th Street

646-988-1544

By John Mariani

Despite

its

refined, romantic design, its 3,000 bottle wine

cache and a

chef with an exceptional career and recognition,

the new Saint Urban, which just opened in the

Flat Iron District this May, is not an easy

place to report on to readers who will not have

a chance to eat anything I recommend on a menu

that will be totally changed each and every

month to come.

It is the same dilemma the Michelin

Guide wrestled with for years in deciding

whether or not to review a restaurant named Next

in Chicago because the entire menu changed from

Modernist Italian to Parisian 1906 to––I

kid you not––interstellar space.

It

is a slippery slope Chef-and Sommelier owner Jared

Ian Stafford-Hill has set for himself, after

relocating Saint Urban from Syracuse (where it was

by default the finest restaurant in Northern New

York) to a Manhattan space that once housed the

wine-focused Veritas, where he once worked. Prior

to that his résumé included stages at Craft, Adour

by Alain Ducasse, Gramercy Tavern and Union

Pacific, all in New York.

It

is a slippery slope Chef-and Sommelier owner Jared

Ian Stafford-Hill has set for himself, after

relocating Saint Urban from Syracuse (where it was

by default the finest restaurant in Northern New

York) to a Manhattan space that once housed the

wine-focused Veritas, where he once worked. Prior

to that his résumé included stages at Craft, Adour

by Alain Ducasse, Gramercy Tavern and Union

Pacific, all in New York.

The décor is completely new and enchanting. Designed

by Bentel & Bentel (they also did The Modern

and Eleven Madison Park), it is not exactly

minimalist but dispenses with flourishes. Largely

it is done in earthen-gray stucco walls and

finished oak, with splendid glowing glass-leaf

sculptures overhead

and slatted wood  louvers

evoking

vine trunks. There is a pleasing contemplative

ambience about the dining room, with a smaller

room up at the entrance, and the focus on wine is

clear from the moment you sit down. Saint Urban,

by the way, was a Franco-German bishop deemed the

patron of winemakers.

louvers

evoking

vine trunks. There is a pleasing contemplative

ambience about the dining room, with a smaller

room up at the entrance, and the focus on wine is

clear from the moment you sit down. Saint Urban,

by the way, was a Franco-German bishop deemed the

patron of winemakers.

The whole staff is wine-imbued and very

knowledgeable, as they should be with a list as

long and comprehensive as St. Urban’s. Stemware

varies from wine to wine and all the amenities at

the table are first rate.

Stafford-Hill offers a four-course

themed tasting menu at $148, seven

courses at $188 and nine courses, called “Truffles

and Unicorns,” at $235, plus wine pairings at

three different levels of quality for $90, $175

and $410. The tasting menus are, by comparison to

similar ones around New York, something of

bargain––Restaurant Daniel, for instance, charges

$235 for five courses; at Jean-Louis $298 for six;

at Per Se $425.

I

can readily say that the food, wine and service at

Saint Urban are all impressive, but my remarks on

what my wife and I were served are strictly based

on the July menu featuring Tuscan cuisine. This

was preceded by that of the Loire Valley in April;

the Cȏte de Beaune in May; Spain in June; and, to

come, the South of France in August and the

southern Rhȏne in September. Which, of course,

begs the question how can any chef, however

experienced and talented, embrace so many cuisines

with authority while refining them with his own

take?

I

can readily say that the food, wine and service at

Saint Urban are all impressive, but my remarks on

what my wife and I were served are strictly based

on the July menu featuring Tuscan cuisine. This

was preceded by that of the Loire Valley in April;

the Cȏte de Beaune in May; Spain in June; and, to

come, the South of France in August and the

southern Rhȏne in September. Which, of course,

begs the question how can any chef, however

experienced and talented, embrace so many cuisines

with authority while refining them with his own

take?

I can only report that we dined with

pleasure in July, with all dishes matched to

appropriate wines and vice-versa.

At

once a puffy, olive-oil moistened rosemary-flecked focaccia

and softened butter is presented while you sip a

small aperitif. Three amuses bouches

appeared––tender green fava beans with pecorino,

lentils, oregano and

olive oil; panzanella salad with a

confit cherry tomato, cucumber, basil, smoked

mozzarella and crouton; and braised Romano

beans, with Tuscan sofrito and opal

basil.

There

is some choice within the courses to follow. We

began with a lustrous slice of bluefin tuna (tonnato),

dressed with basil and summer’s beans. There were

two pastas: a rich dish of cappelletti

with sweet corn, morels and a dash of

pecorino. Small, tender gnocchi were arrayed in a

ragù of winey wild

boar.

There

is some choice within the courses to follow. We

began with a lustrous slice of bluefin tuna (tonnato),

dressed with basil and summer’s beans. There were

two pastas: a rich dish of cappelletti

with sweet corn, morels and a dash of

pecorino. Small, tender gnocchi were arrayed in a

ragù of winey wild

boar.

Wonderfully flakey and

velvety poached sea bass was afloat in a deeply

reduced minestrone aqua pazzo, while the

Livornese seafood stew called cacciucco

contained ample morsels of langoustine tail and

snowy cod flavored and made aromatic with fennel

and lemon. (Traditionally this dish contains

five species of seafood like red mullet and scallops. )

red mullet and scallops. )

Crisp-skinned guinea hen

cacciatore (hunter’s stye) with

peppers and wild mushrooms was a more subtle

dish than its name suggests, and then came a

rectangle of beef called “alla fiorentina,”

which would suggest a crusted but very rare

ribeye, but this was instead closer to tournedos

Rossini, in a luxuriously reduced demi-glace,

almost as thick as chocolate syrup, served with

eggplant, well-roasted onion and salsa verde. (Incidentally,

it’s good to see sauce spoons on the table here

so one can lap up every bit of such savory

sauces.)

Before dessert there was

a slice of fine pecorino with arugula and

chestnut honey, followed by a simple olive oil

cake with summer fruits and delightful ricotta

sorbet.

With

each of these courses carefully selected Tuscan

wines were poured, from a Montenidoli Vernaccia

di San Gimignano Carato 2019 and a Gaja

Ca'Marcanda Vistamare 2022 to Campriano Chianti

Classico Riserva 2012 s Fontodi Chianti Classico

2008 and a Casanova della Spinetta Toscana

Sassontino 2006, among others.

With

each of these courses carefully selected Tuscan

wines were poured, from a Montenidoli Vernaccia

di San Gimignano Carato 2019 and a Gaja

Ca'Marcanda Vistamare 2022 to Campriano Chianti

Classico Riserva 2012 s Fontodi Chianti Classico

2008 and a Casanova della Spinetta Toscana

Sassontino 2006, among others.

It was a meal to applaud,

and I would have loved for you, the reader, to

have the opportunity to enjoy it, too, but you

may have to wait another summer to do so. I can

readily understand why high-caliber chefs like

Stafford-Hill want to showcase their command and

technique in a wide array of dishes, and, had

the word “Tuscan” been taken off the July menu,

it might have been served as a meal of the season.

But I’m afraid you’re on your own if you go this

month or next or the one after that. Let me know

how it is.

Open Tues.-Sat. for

dinner.

HÔTEL ALLEMAGNE

By John Mariani

Kōvar said, “It

was a very excitable night, I can tell you

that. It was about eight o’clock, and I had

just come back from dinner with a Russian

friend who was also staying in the hotel. We

had had a Cognac in the bar, then I went

upstairs to bed. I was in the bathroom when

all of a sudden I began to feel strangely

fatigued. I thought it was the wine and the

Cognac, though I’d never felt quite that way

before. I

went to bed and fell asleep quickly, but when

I woke up I was feeling a little dizzy at

first. I went in to sit on the bed, and my

breathing became heavy and I started to cough

violently. In some ways it felt like a flu

when it first begins, but this was very, very

fast. I tried to lie down and let it pass but

by morning it was becoming more difficult to

breathe every moment. My head started

pounding, too. This was just not normal.”

“What time was this?” asked David.

“About nine in the morning. Then,

outside my room I heard a great deal of

bustling about, so I opened the door and found

all these people in the hallway, many of them

coughing and most bracing themselves on the

hotel wall. I was walking very weakly, trying

not to fall over. I passed my Russian friend’s

door and banged on it but there was no answer,

so I kept on to the stairs. We were only on

the third floor so some of us walked down,

holding onto the banister. From the first

floor landing I could see, I don’t know, ten,

fifteen people in the lobby, some sitting in a

chair and others collapsed on the floor. The

hotel night staff also showed signs of

illness. Within moments more people staggered

down the stairs and others literally fell out

of the elevator door when it opened. It was

terrible, and women started to scream in

panic.

“It felt like an eternity but I later

learned the police and the ambulances were

there at the front door within minutes. Next

thing I knew I was being placed on a stretcher

and carried to an ambulance. By then there

must have been a dozen ambulances at the

hotel, and the last thing I remember before

passing out was the sound of police cars and

emergency vehicles’ blaring horns coming from

all directions.

“I woke up in the hospital around five

o’clock that evening with an oxygen tube in my

nose.”

“It all sounds terrifying,” said

Catherine. “Not knowing what the cause was.”

“At first I thought it was some kind of

gas attack,” said Kōmar, “even though I didn’t

smell anything. There was no smoke, no

explosion. In the hospital I was told that it

had been some kind of germ that had gone

through the hotel and sickened everyone, or at

least those below the seventh floor. Only

later that day did I heard about the incidents

at the other two hotels. It’s a terrible,

terrible tragedy. But, at least no one has

died from it. Yet.”

“Did you ever find out what happened to

your Russian friend?”

“Ilya? No, I didn’t see him in the

lobby when I stumbled down there. I remember

that the

night before he got into the elevator

with me just before the door closed. We went

up to the third floor and I said, ‘After you,

Ilya,’ but he said he was going up to another

floor. Which was odd, now that I think of it,

because his room was on the third floor where

mine was. I don’t know where he was going.

Maybe a business associate.”

“So, this would have been before ten

o’clock?” asked David.

“Yes, perhaps eighty-thirty or nine. I

started feeling really sick about around

midnight.”

The three Americans looked at each

other, and Catherine asked, “Have you been in

touch with this Ilya since the attack?”

“No, we were not so close that he would

come see me in the hospital, assuming he was

not ill. Besides, all the patients were

restricted from having visitors until we were

released.”

“So, you

don’t know if Ilya did become sick or not,”

said Katie.

“So, you

don’t know if Ilya did become sick or not,”

said Katie.

“No, I have no idea. He’s attached to

the Russian Embassy here so you might inquire

here.”

“I think we’d better,” said David,

glancing at Katie and Catherine.

They did so immediately by showing up

at the embassy on the Boulevard Lannes, just

off the Bois de Boulogne. It was a brutishly

modern structure with not a single reference

to French architectural tradition. It was very

wide, with two floors composed of two slabs,

with an endless series of banal rectangular

windows and a rooftop with visible heating and

air-conditioning units and other box

structures containing whatever it was they

contained.

The interior lacked any decorous

interest as well, and it reminded Katie of the

dreary quarters of the Russian security

service headquarters in Moscow that Katie and

David had visited on another investigation.

There was a long desk manned by three

attendants and four armed soldiers milling

around the lobby.

Catherine spoke to an attendant in

French, explaining that they she was a

journalist from CNN International and these

were journalists from the United States.

“We’d like to inquire if Ambassador

Ilya Bazarov would be available to speak with

us.”

The woman asked what this was in

reference to. Catherine said they were

interviewing people who had been at the Hôtel

Anastasia the night of the event. The woman

said nothing but made a phone call, speaking

in Russian. Two minutes later she picked up

the phone, saying several times, “Da. . .

da. . . da,” hung up then said, “I am

afraid the Ambassador cannot see you at this

time, but if you wish to e-mail some

questions, I will see that he gets them.”

Catherine said thank you and left her

card, in case the ambassador wished to speak

with her directly. The woman nodded, hit a

buzzer to open the door and said, “Au

revoir.”

“That’s about the way I thought it’d

go,” said Catherine, outside.

“I’m sure Ilya is a very busy man,”

David said sarcastically.

“And I’m sure he would never answer our

questions without having them in writing, then

gone over by his superiors, if they’d let him

answer at all.”

David suggested their next stop should

be to talk with Catherine’s concierge friend

at the Anastasia. Katie said, “Why don’t you

two go ahead. I’m going to try to speak with

Dr. Baer as to any update on the virus.”

Katie took the Métro back to her hotel,

while Catherine attempted to reach her friend

Yves, whose phone recorder said he would call

back as soon as possible.

“What now?” asked David.

“Well, I’ve got to hustle to get to the

fashion show. It’s Courrèges today, then

Lagerfeld.”

“Okay, I’ll just stroll the boulevards.

I have to pick up my new jacket, too.”

When he was a cop, David

knew most every neighborhood in New York and

felt knowledgeable about most of them. He even

spoke a little street Spanish, so he could

make himself understood in various Latino

neighborhoods. On the rare occasions he had

been in a foreign country—outside of London

and Dublin—he usually only had contact with

English-speaking colleagues in the police

departments. Katie had been able to handle

Italian and French well enough so that he felt

pretty comfortable when they had travelled to

Rome, Naples and now Paris.

Now here he was feeling sheepish and

lost, reluctant to ask anyone for directions,

still queasy about how to plot a trip on the

Métro, and, even though he was getting hungry

for lunch, he felt funny about opening a menu

all in French. Why do so few Parisians speak

English? he thought. So, to alleviate any

fears of appearing like a total American jerk,

he simply returned to his hotel and had lunch

there. About an hour later, that’s where Katie

found him finishing off a slice of tarte Tatin

and coffee.

Katie knew enough not to ask a question

like “What are you doing here?” knowing it

would sound like she knew the reason why David

was having lunch in a safe place. So, she just

said, “Hey, I’m glad you’re here. I just got

off the phone with Baer and Catherine called

and said we could go over to Yves’s apartment

to speak with him this afternoon at four.”

“Great news,” said David, signing his

check. “Gives us time to pick up my new

jacket. So, what did Baer have to say?”

“She said that most people were being

let out of the hospital and that they’re no

longer infectious. Which means there are a lot

more potential guests we could interview, I

suppose. I asked her how serious the virus

was, and she said that it had been carefully

engineered not to be a killer,

although the immediate effects were far more

debilitating than a seasonal flu. She said

that many of the elderly patients would

probably remain in the hospital, and a few had

developed pneumonia, which kills more old

people than the virus itself, so there could

still be some deaths.”

“Meaning that whoever stole this

particular virus knew that it was not all that

deadly,” said David. “And that means that the

attack was more of a scare tactic.”

“Uh-huh, a tactic that would

effectively put the hotels out of commission

for a long time.”

“Did Baer say how long?”

“She said it’s hard to tell because,

first, it’s a brand new virus, and second,

because even if you scrub down and fumigate

every interior surface, it could linger deep

in the recesses of the air ducts for who know

how long.”

“So, there’ll be no way anyone will

want to stay at those hotels until there’s a

guarantee every trace had been wiped out.”

“That’s what she suggested would be the

case. And even after the hotels tell everyone

they’re absolutely in no danger, how many

people are going to take the chance?”

“Which all coincides with our theory

that this incident was not just to hurt and

embarrass the Saudi owners but to make the

value of the properties plummet.”

“Frankly,” said Katie, “Whatever the

Saudis spent to buy those hotels is a drop in

their bucket, or should I say just a few

buckets of oil. They must also be insured. I

don’t know what French insurance companies are

like, but this was obviously no act of God. I

don’t know where they stand on terrorist

attacks.”

“Neither do I,” said David, “but I hear

the insurers of all the 9/11 businesses are

eventually going to have to pay billions.”

“Well, we’ll see. Baer did say she

didn’t expect any more widespread infections,

although the people who did not get sick that

night may not have had symptoms and might have

carried the virus to wherever they went after

the incident, but it’s a low probability.”

The two had a couple of hours before

the meeting with Yves, so they walked over to

the men’s store to pick up David’s new jacket.

He’d even put on a fresh shirt for the event.

“Whaddaya think?” he said, hunching his

shoulders up and down, the way men do when

putting on a new jacket.

“You look really good, very. . .

debonair?”

“Maybe I

should buy a beret and start tying my scarf

the way they do over here.”

“One

step at a time, Monsieur, one step at a time.”

David

had to admit the jacket looked and fit a lot

better than his old blazer. “Makes me look

taller,” he said, pulling down his shirt

cuffs.

He paid the bill—which was

more than twice what he’d ever paid for a

jacket—extended his arm to Katie and said,

“Well, Mademoiselle, may I have the pleasure

of a stroll through Par-ee with you?”

© John Mariani, 2024

❖❖❖

THE WINES OF MICHIGAN

By John Mariani

Michigan

homeboy Ernest Hemingway wrote that

“wine is one of the most civilized things in the

world and one of the natural things of the world

that has been brought to the greatest perfection.” If he could

return to the state today, he’d find a flourishing

wine industry. Ten years ago the state had 56 vineyards

spread over 1,800 acres, producing 425,000

cases,

13th in the nation for wine production. Today the number of

wineries in Michigan is 258 wineries spread over

3,300 acres of vineyards, bringing in more than $5.5 billion in

wine sales and ecotourism; the state ranks seventh

in the US for wine production.

Michigan

homeboy Ernest Hemingway wrote that

“wine is one of the most civilized things in the

world and one of the natural things of the world

that has been brought to the greatest perfection.” If he could

return to the state today, he’d find a flourishing

wine industry. Ten years ago the state had 56 vineyards

spread over 1,800 acres, producing 425,000

cases,

13th in the nation for wine production. Today the number of

wineries in Michigan is 258 wineries spread over

3,300 acres of vineyards, bringing in more than $5.5 billion in

wine sales and ecotourism; the state ranks seventh

in the US for wine production.

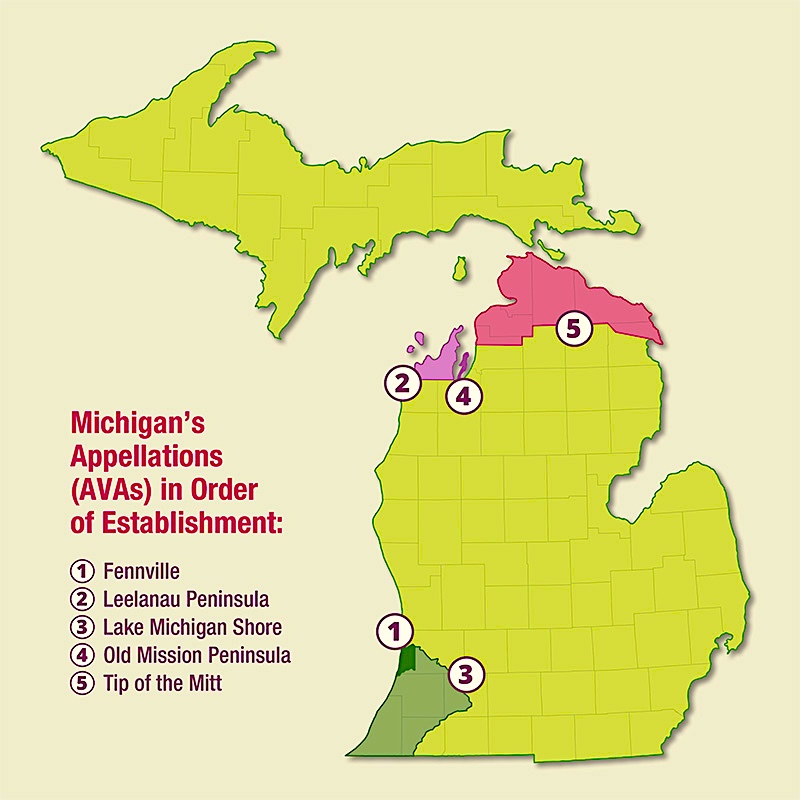

Most of

the quality bottled wine of Michigan is produced in

the five American

Viticultural Areas (AVAs) of

Fennville, Lake Michigan Shore, Leelanau Peninsula,

Old Mission Peninsula and the Tip of Mitt. The Upper

Peninsular is also gaining in interest and number of

wineries.

is produced in

the five American

Viticultural Areas (AVAs) of

Fennville, Lake Michigan Shore, Leelanau Peninsula,

Old Mission Peninsula and the Tip of Mitt. The Upper

Peninsular is also gaining in interest and number of

wineries.

I was surprised to find that

while some wineries still use foxy native grapes

like Concord ice wines do well in the cold

north––overwhelmingly sweet wines up through the

1970s, but these days more are using

French-American hybrids like Vignoles and

Chambourcin and European varietals like Riesling,

which does

well in cold climates. Northern Michigan areas like

Traverse City, the Leelanau Peninsular, and the Old

Mission Peninsular with more temperate microclimates

do well with chardonnay and merlot. The warming of

the climate should be a boon to the industry in the

future.

Michiganders

are very proud of their wines, ubiquitous in wine

stores, groceries, and restaurants, and the vintners

seem to delight in giving their wines catchy, even wacky names, like Left

Foot Charley, Karma Vista, Fishtown White, Sex,

Detention, and Hotrod Cherry, along with Madonna,

made by Silvio and Joan Ciccone, who happen to be

the pop star’s mother and father.

What to look for?

My favorites after a week of drinking only Michigan

wines included the

bright, refreshing Bowers Harbor Vineyard Riesling

($15) from the Old Mission Peninsula (above).

Also

fine was Chateau Grand Traverse Dry Riesling ($13),

with a fresh, clean, briskness. The best red wine I

tried was also from Bowers Harbor, a pinot noir with

true varietal flavor reminiscent of some of the best

out of Oregon, if not quite up to French Burgundy.

By the way, Michigan law

permits shipping to “reciprocal states” only, so

best check with Fed-Ex if you can get receive them

where you live.

If so, try Folgarelli’s Wine Shop in Traverse

City (231-941-7651).

❖❖❖

ACQUIRED TASTES NO

ONE NEEDS TO ACQUIRE

"To make skerpikjot, the signature dish of Faroese cooking, a freshly slaughtered lamb must be hung out to dry in the mineral-rich islands’ winds for so long that it starts to ferment. Then, reeking of death and coated with a fine layer of mould, the meat is ready to eat. It would be underselling it to describe skerpikjot as an acquired taste. While universally popular among Faroe Islanders, those from overseas may struggle to develop an appreciation."––"I tried mouldy lamb at the world’s most remote Michelin-star eatery at Paz in the Faroe Island." The London Times (7/25).

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher

Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish.

Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2025