MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

February

8, 2026

NEWSLETTER

Founded in 1996

ARCHIVE

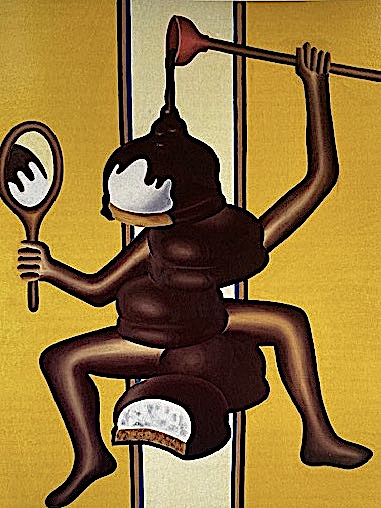

"Mallomars" By Frank Kostabli (1967)

REMEMBERING LAURA MAIOGLIO

OF BARBETTA

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

THE FLOWER SHOP

By John Mariani

THE BISON

CHAPTER NINE

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

DRINKING WINE WITHOUT FOOD IS LIKE

WEARING A TIE WITHOUT A SHIRT

By John Mariani

REMEMBERING

LAURA MAIOGLIO

OF BARBETTA

By John

Mariani

Laura

Maioglio, the owner and curator of Barbetta, one

of New York’s most legendary restaurants, died

January 17. And, according to its website, it,

too, will pass from history at the end of

February.

Regal

in bearing and elegant in dress, Ms Maioglio was

among the last of the doyennes of Italian

cuisine, along with Luisa Leone of Mamma

Leone’s, Sylvia Woods of Sylvia’s, Edna Lewis of

Café Nicholson and Elaine Kaufman of Elaine’s,

whose Piemontese roots transcended the

all-too-familiar clichés of Italian-American

menus of the post-war era.

Although

educated to be an architect, she took over, with

some reluctance, the running and survival of

Barbetta, which was opened in 1906 by Sebastiano

Maioglio (whose brother Vincenzo’s little beard

gave Barbetta its name) and his wife, Piera, at

its original location on West 39th Street, later

moving to a three-story townhouse on West 46th

Street in the heart of the Theater District,

where it drew

the theater and music stars of every decade,

from Puccini and Caruso to Mick Jagger and

Madonna.

Although

educated to be an architect, she took over, with

some reluctance, the running and survival of

Barbetta, which was opened in 1906 by Sebastiano

Maioglio (whose brother Vincenzo’s little beard

gave Barbetta its name) and his wife, Piera, at

its original location on West 39th Street, later

moving to a three-story townhouse on West 46th

Street in the heart of the Theater District,

where it drew

the theater and music stars of every decade,

from Puccini and Caruso to Mick Jagger and

Madonna.

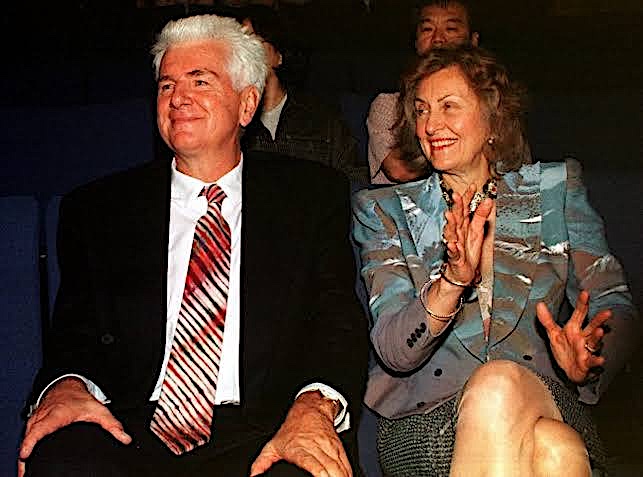

Dr. Günter Blobel and Laura Maioglio

Laura not only maintained but worked to evolve

the décor and cuisine of Barbetta, adding

Piemontese dishes like house-made agnolotti,

risotto with white truffles, roasted rabbit

and polenta, a quail’s nest of fonduta

cheese, tajarine (tagliolini)

with a oven-roasted tomato sauce, and monte bianco, a chestnut cream

topped with snowy whipped cream made to look

like Mont Blanc in Switzerland. Indeed, she

introduced white truffles to New York by

raising her own hounds in Piedmont to ferret

them out. Her wine list was extraordinary,

with more

than 1,700 selections of predominantly Italian

wines.

In 1993, the Italian cultural association Locali

Storici d’Italia designated Barbetta’s interior

a landmark, and in 1996, the Italian government

gave the restaurant the Insegna del Ristorante

Italiano, in recognition for serving the best

authentic Italian food outside Italy.

Laura Clara Maioglio was

born in Manhattan on March 17, 1932, grew up

above the restaurant and graduated from the

prestigious Brearley School. In 1976 she married

molecular biologist Günter Blobel, who was

awarded the 1999

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He died

in 2018.

Through

all

the ups and downs of the restaurant business,

including the downward slump of the Theater

District––she used to feed the Guardian Angels

civilian patrol group in order to keep the drug

dealers off West 46th Street––Ms.

Maioglio kept Barbetta going, made possible by

her family owning the building.

Through

all

the ups and downs of the restaurant business,

including the downward slump of the Theater

District––she used to feed the Guardian Angels

civilian patrol group in order to keep the drug

dealers off West 46th Street––Ms.

Maioglio kept Barbetta going, made possible by

her family owning the building.

Reviews of the

restaurant varied, often because the critics did

not order the Piemontese specialties, including

one Miami-based food writer who based his

opinion on a green salad and plate of spaghetti

with tomato sauce. Others, though, recognized

that Laura was a stalwart in the battle to wean

customers away from the familiar. “I’ve

long

admired and respected the art of the remarkable

creator of Barbetta,” says Bob Lape, long-time

New York restaurant critic for WABC Eyewitness

News, “Every visit was made memorable by the

immersion in visual elegance and

extravagance. So much so it was almost a

surprise to discover time and again just how

wondrously well the food and service

matched the tsunami of eye candy. She was one of

a kind, and we the beneficiaries of her

standard-bearing.”

My own

affections for Barbetta and Laura Maioglio go

back five decades, when entering this

exceptional space was always special and unique

to New York, and a meal outside in the leafy

garden, with is bubbling fountain statue beneath

the stars was the epitome of what makes the city

as glamorous and romantic as it is.

Laura had a

Pre-Raphaelite beauty, with fiery curly hair and

the bearing of Una Grande Signora who

might have once moved easily within the courts

of Piedmont’s House of Savoy. Genteel and

uncompromising, she kept Barbetta running with a

sense of mission bound by traditions that went

far back in her family’s history. And in an

industry still dominated by men, she was an

inspiration for women entering the culinary

profession.

NEW YORK CORNER

THE FLOWER SHOP

107 Eldridge Street

212-257-4072

By John Mariani

Gastropubs

were a good idea when they burgeoned back in

the nineties by basically upgrading the

quality of traditional bar items like

burgers and chicken wings. Most never went

much beyond the familiar, but with the

appointment of Eddie Huang as exec chef at

The Flower Shop the ante has been

upped.

After

a successful pop-up stint called the Gazebo at

The Flower Shop last summer, Huang found what

he’d been looking for since closing his own

restaurant Baohaus and turning to writing his

memoir, Fresh Off the Boat, which was

turned into an ABC TV series, as well as

writing and directing the Taylour Paige and

Pop Smoke film Boogie, and directed

and

After

a successful pop-up stint called the Gazebo at

The Flower Shop last summer, Huang found what

he’d been looking for since closing his own

restaurant Baohaus and turning to writing his

memoir, Fresh Off the Boat, which was

turned into an ABC TV series, as well as

writing and directing the Taylour Paige and

Pop Smoke film Boogie, and directed

and

starred in his second

feature,

Vice is Broke.

His return to The Flower Shop, opened

in 2017 by Dylan Hales and Ronnie––there’s a

branch in Austin, Texas––increases interest in

what had been a successful bar drawing a

fashion and arts crowd to the cusp of

Chinatown and the Lower East Side. The place

itself hasn’t changed, with its main bar at

ground level, with comfortable booths along a

wall filled with sketches of city life.

Piped-in music makes it louder than it need

be. Downstairs is a basement bar with pool

table, TVs and sunken living room.

The reception is very

cordial, the service on spot, and Huang is in

and out of the kitchen to bring plates and

describe them.

His is a playful menu with nothing very

complex, reflecting his own food culture and

others he’s experienced, revving up what a

gastropub should be in 2026. There are small,

medium and large plates, with the highest

priced item $30.

General Tso's Skate

Wing takes the Buffalo chicken classic and

gives it a Taiwanese spin applied to a whole

fried skate wing finished with orange zest (right).

A

typical Spanish tortilla is treated to flavors

of a garlic chive dumpling featuring sesame

oil, white pepper, and a dash of soy sauteed

with duck fat to give it a richer coating (left).

Duck fat is also the medium for some

delightful crispy, vinegared fries of a kind

you’d find at a stall in Taiwan’s Shilin Night

Market, which accompany the menu’s most

impressive dish of long-braised

confit of duck leg with a garlic chive and

cognac brown braised soy sauce and a balancing

squirt of lemon.

A

typical Spanish tortilla is treated to flavors

of a garlic chive dumpling featuring sesame

oil, white pepper, and a dash of soy sauteed

with duck fat to give it a richer coating (left).

Duck fat is also the medium for some

delightful crispy, vinegared fries of a kind

you’d find at a stall in Taiwan’s Shilin Night

Market, which accompany the menu’s most

impressive dish of long-braised

confit of duck leg with a garlic chive and

cognac brown braised soy sauce and a balancing

squirt of lemon.

I loved the Asiatic

slaw, as much for its textures as for its

Asiatic seasonings, but I found the pappadaw

and olive potato egg salad  very

bland.

very

bland.

X.O. Caesar salad is

made with arugula rather than romaine lettuce

and combined with parmesan, chili oil

breadcrumbs. dried scallops and pulverized

dried shrimp with X.O. sauce.

A traditional

Shanghai-style crispy garlic blackfish is

seared and then served with pickled Fresno

peppers, scallions, ginger, and a seafood

soy.

As noted, every

gastropub needs a burger, and The Flower Shop

has three. Two with beef, one called a

Cantonese Wedding Fish Sandwich (right).

It’s a terrific

variation that begins with meaty cod

fried in walnuts and panko then brushed with a

housemade Sichuan chili oil honey crisp. It is

then roasted under the red hot salamander and

served on a sesame seed bun from Pain

d’Avignon painted

with citrus-honey mayonnaise and topped with slaw.

It’s a massive tour de force not to be missed.

You expect flank steak to

be a little chewy, but Huang’s is made with

wagyu beef, so you’d think it would be more

tender. It is seasoned with salt and white

pepper, basted with clarified to gild the lily

and finished with a Hunan red cooking

braise lashed with Cognac and cream to mimic

steak au poivre.

You expect flank steak to

be a little chewy, but Huang’s is made with

wagyu beef, so you’d think it would be more

tender. It is seasoned with salt and white

pepper, basted with clarified to gild the lily

and finished with a Hunan red cooking

braise lashed with Cognac and cream to mimic

steak au poivre.

You might also expect

pork belly to be velvety with fat but the

Iberico pork was

beyond chewy, despite being marinated

in two Taiwanese vinegars, goat’s cheese

stuffed peppadews and Castelvetrano olives

served with a Sichuan-Basque potato salad of

proprietary chili oil, garlic crisp, creamer

potatoes, peppadaw/olive brine, garlic chives,

and kewpie mayo.

There are just two

desserts: A miso apple pie with Schlag whipped

cream, and that beloved New York classic

cookie, the black-and-white, made famous in a

1994 episode of Seinfeld, when Jerry explains

to Elaine, “The key to eating a

black-and-white cookie is you want to get some

black and some white in each bite. Nothing

mixes better than vanilla and chocolate, and

yet still somehow racial harmony eludes all of

us. If people would only look to the cookie

all our problems would be solved.” Maybe not,

but Huang is giving it a gung-ho try.

The bar has several

signature, along with a perfect Hemingway

Daiquiri, ten beers but only eight wines (all

available by the glass).

Nothing

on Huang’s menu is quite what you expect, and

it is supposed to be fun, however serious he

is about making it his own.

Open for dinner

Tues.-Sat.

THE

BISON

CHAPTER

NINE

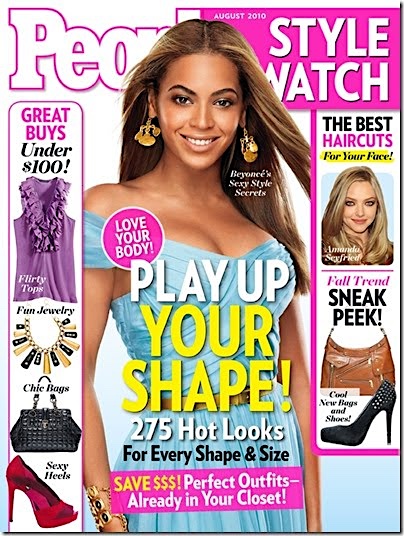

More

and more Katie thought all those she’d

interviewed had the same vision for New

York magazine, which she didn’t

find all that original. True, Talk magazine

had flopped trying to cover uptown and

downtown in the same pages as

a must-read tabloid would, but

People magazine had for years

already been covering Black

entertainers, hip hop and the transition

of Disney’s TV child actors into major

pop culture stars that People was

only too happy to help happen. Then

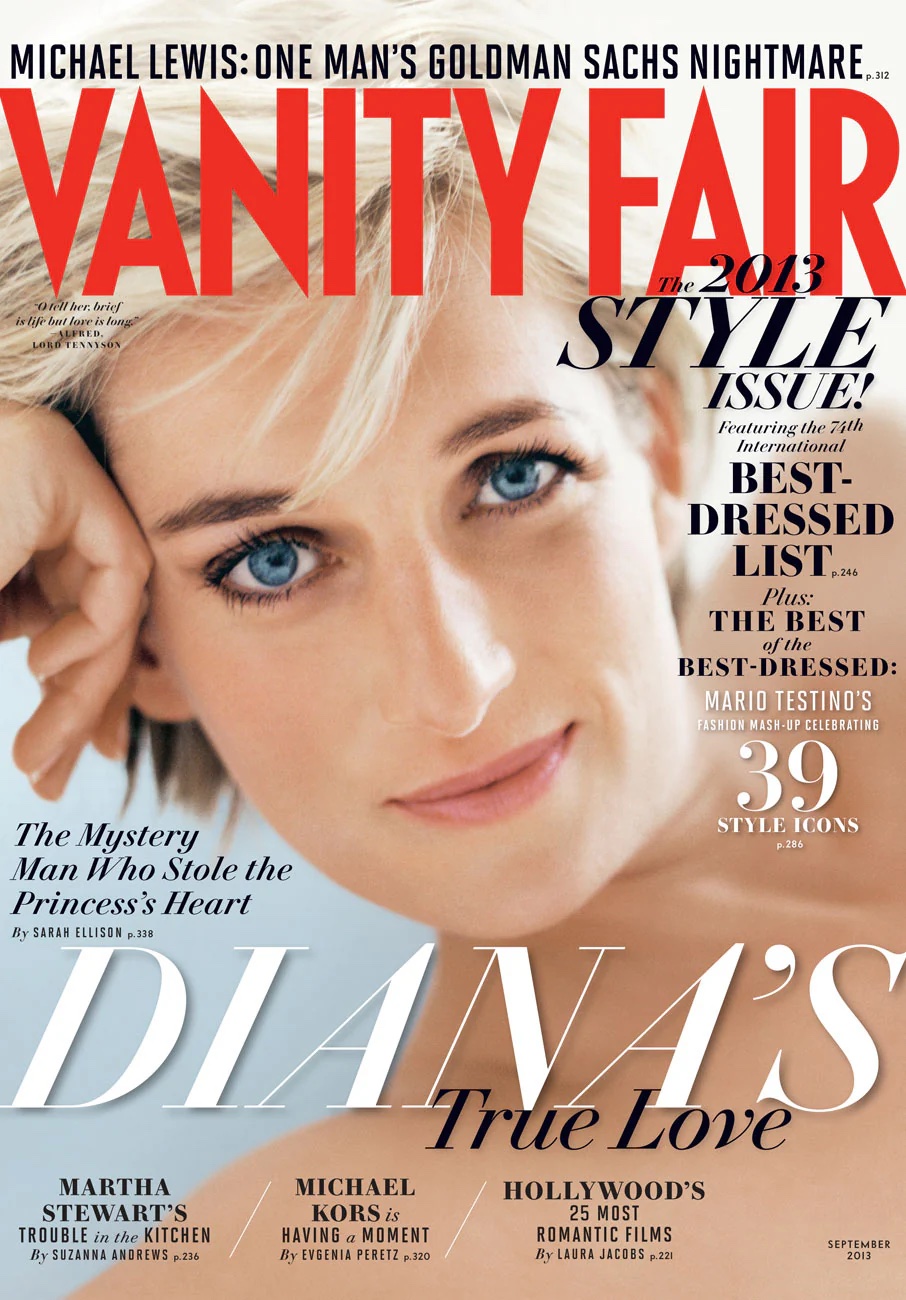

again, Vanity Fair had only a

fleeting interest in pop culture that

was not mainstream glamor or high-class

scandal.

More

and more Katie thought all those she’d

interviewed had the same vision for New

York magazine, which she didn’t

find all that original. True, Talk magazine

had flopped trying to cover uptown and

downtown in the same pages as

a must-read tabloid would, but

People magazine had for years

already been covering Black

entertainers, hip hop and the transition

of Disney’s TV child actors into major

pop culture stars that People was

only too happy to help happen. Then

again, Vanity Fair had only a

fleeting interest in pop culture that

was not mainstream glamor or high-class

scandal.  Even Princess Diana, who

had died five years earlier, could sell

more copies if Graydon Carter stuck her

on the cover than any up-and-coming

challenger to Madonna. The so-called

super models of the nineties had faded

from the covers quickly.

Even Princess Diana, who

had died five years earlier, could sell

more copies if Graydon Carter stuck her

on the cover than any up-and-coming

challenger to Madonna. The so-called

super models of the nineties had faded

from the covers quickly.

The way things were shaping up,

her story was going to be very

repetitious if all the bidders for New

York were after the same thing. And

that was not something she expected to

get from the Wall Street banker types

who were in the bidding. Except for the

South African Angus Pierce, all the

bidders were powerful New York Jewish

men, all of whom, except Deutsch, had

married non-Jewish trophy wives, what

Jewish-American novelist Philip Roth

(whose principal fictional character was

named Zuckerman) had called

“hypergamy—bedding women of superior

social class.” Each, except Weinstein,

had joined a club of New York

millionaires and billionaires who were

constantly in competition, circling the

ring like smiling Cheshire cats who

could sometimes agree to work together

to mutual benefit. For each, New

York magazine was another trophy,

but one they all insisted on should turn

a profit. These men were so rich that

they could afford to lose millions every

year and keep pouring more in to right a

sinking ship.

Katie

had always thought of herself in some

ways as Alice in Wonderland, going down

rabbit holes, being tricked and given

false leads, always trying to find the

truth of a story in a world of

obfuscation. Actually her favorite

character in Alice was the

Cheshire Cat who had said, “We are all

victims in waiting,” and who seemed to

sum up why very, very wealthy men are

always restlessly trying to find more:

Only a few find the way, some don’t

recognize it when they do—some don’t

ever want to.”

Katie’s

familiarity with Angus Pierce was only

because he was a media baron. As

Zuckerman had said, he

was, with Murdoch and Maxwell,

considered one of the three titans of

the media business whose strategy

was always to attack competitors’

underbelly, often bidding way over the

value of a company, even if that company

would later be incorporated into another

or killed outright.

Their politics went with the

prevailing winds of probability, and they

were willing to contribute to a winning side

on the assumption that there would be

pay-back at some future time. Recognizing

that paper tiger politicians could be more

valuable than men of integrity, the trio had

always backed those who had media charisma

without the underlying intelligence. It was

a shell game at which the men shuffling the

shells always won.

Pierce

stayed away from the limelight, only giving

interviews to reporters from Pierce-owned

newspapers or media stations. Like

others among the bidders, Pierce was known

to stay at Epstein’s mansion when he came to

New York, where he enjoyed complete privacy

from the press.

There was no set

deadline for the bidding to end but Katie

knew it would be in the very near future.

She was hoping for someone like Epstein or

Weinstein to win the prize because she saw

them as more colorful characters for her

story. The word was that New York’s

circulation of

432,000

had fallen in 2002 and the magazine had earned less

than $1 million on revenue of $43.6 million

that year.

Her phone

rang the next morning. It was Dobell.

“The sale of New York was

just announced,” he said.

Katie was surprised at the suddenness

of the news.

“So who got it?”

“Wasserstein

(left). Paid $55 million for it, along

with assuming $8 million in liabilities.”

“Wasserstein

(left). Paid $55 million for it, along

with assuming $8 million in liabilities.”

“He’s

got that kind of money?”

“Apparently he

does. He had sold his investment bank for

$1.37 billion in stock and is using his own

assets through his New

York Media Holdings.”

“Where’s this news coming from?”

“It’s

in both the Times and the Post.

Apparently he bid $10 million more than

anyone else, which is why—it says here—they

call him ‛Bid-em-up Bruce.’ Zuckerman was

the front runner and thought he had the deal

sewn up. It also turns out Zuckerman had

hooked up with Pelts, Epstein, Weinstein and

Deutsch.”

“Jesus!” said Katie,

trying to wrap her head around the idea that

all those she’d interviewed had been in bed

together on the deal. She only regretted

that she hadn’t gotten to Wasserstein before

the sale went through.

Dobell read from The

Post report: “‛We believe New York

has significant long-term value and growth

potential,’ Mr. Wasserstein said in a

statement. ‛It is the leading magazine for

successful New Yorkers and we intend to

build from this position to enhance this

historic franchise and extend the brand.’"

There was a pause, then

Dobell said, “Lemme ask you, Katie. Have you

still got a story here?”

“Well, we’d agreed the

story would go beyond the sale, and . . ."

“And what? I don’t

see it going anywhere.”

“Let me think it

over. The personalities in this whole

scenario are fascinating, powerful men who

share a lot of traits.”

“But

with five of them bidding together, it kind

of dissipates the rationale for a story. I

can’t let you dig into something so vague.”

“I

understand, Alan, just let me give it some

thought.”

“Fair

enough. You coming into the office now?”

“Yeah,

be there in an hour.”

Katie

was suddenly feeling very empty, especially

of new ideas.

❖❖❖

WINE WITHOUT FOOD IS

LIKE

WEARING A TIE WITHOUT A SHIRT

By John

Mariani

Centuries––millennia

really––of praise lavished on wine as a

divine drink have unfortunately obscured the

reality that wine drunk on its own

diminishes the pleasure that would otherwise

be had by drinking it with food.

It’s like listening to a baseball game on the

radio or shadow boxing. It’s like Reader’s

Digest or visiting only Hong Kong on a

trip to China.

Wines’ first usage was to go with food, and

one may assume the earliest efforts, in the

Caucasus region about 8,000 years ago, were

modest. The idea that wine, containing

alcohol, was a better alternative to drinking

contaminated water came along when people

moved into cities. Yet the effect of wine,

which the Bible calls a gift of God, has

certainly been disassociated from its role as

an accompaniment to food––even if the

enjoyment leads to tipsiness or drunkenness.

Wines’ first usage was to go with food, and

one may assume the earliest efforts, in the

Caucasus region about 8,000 years ago, were

modest. The idea that wine, containing

alcohol, was a better alternative to drinking

contaminated water came along when people

moved into cities. Yet the effect of wine,

which the Bible calls a gift of God, has

certainly been disassociated from its role as

an accompaniment to food––even if the

enjoyment leads to tipsiness or drunkenness.

To be sure, there are

plenty of wines that can serve as an aperitif,

though it’s always questionable when a person

just orders “a glass of dry Chardonnay,” which

shows about as much discrimination as buying a

pair of black socks. Even then, that

Chardonnay’s middling virtues will be enhanced

when sipped with snacks, canapes or appetizer,

whether it’s pretzels, shrimp cocktail or

sushi.

Drinking red wines all on their own is even a

little ridiculous, because

their flavors and tannin lack the stimulus

that food, especially fat or some kind,

provides. Whether it’s with a hamburger or

ribeye, a red wine will always taste better

than on its own.

For the same reason eating

food without a beverage makes no sense––and

water doesn’t do anything at all for the beef,

onions, cheese and ketchup involved. Wine

writers are constantly pairing up what they

insist is the ideal wine to go with a specific

dish, but the options are so numerous for any

dish as to be little better than the advice of

having white wine with seafood and red wine

with meat.

There

are wholly natural pairings that make perfect

sense when it comes to the food and wine

within a region. Why would anyone eating, say,

Sicilian food order a French Burgundy or

serving a dish of Spanish paella with a German

Riesling? After all, the grapes of a

region––sometimes indigenous––grow in the same

soil as the food, and that soil contains the

same nutrients and minerals absorbed by the

grapes.

Take, for example, a modest

Italian white like Vermentino, once a

workhorse grape, very light, very pale and in

the past indistinguishable from others. But

modern examples are not only better but show

off their regional character, so that the

Tenuta Ammiraglio Massovivo Vermentino 2024

($22) from Tuscany that comes from seaside

vineyards is quite different from the Val

delle Rose “Litorale” 2024 ($20) from

Maremma’s inland vineyards and Olianas

Vermentino di Sardegna 2024 ($23) from the

terroir of the island in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

So, too, an oaky, vanilla-rich Chardonnay from

Napa Valley is going to taste a lot different

from a more subtle example from Oregon’s

Willamette Valley. New Zealand  Sauvignon Blancs

like Cloudy Bay are mostly

made into a sweet style almost like punch,

whereas those from the Loire Valley have more

tempered fruit, vegetal and mineral flavors

that go with the local goods like goat’s

cheese, rillettes of pork, perch in a beurre

blanc.

Sauvignon Blancs

like Cloudy Bay are mostly

made into a sweet style almost like punch,

whereas those from the Loire Valley have more

tempered fruit, vegetal and mineral flavors

that go with the local goods like goat’s

cheese, rillettes of pork, perch in a beurre

blanc.

If

any rules should apply with regard to wines,

it should be that they match up with the food

traditionally produced by growers and cooks

who know from long experience that the Pinot

Noirs from California or Australia taste very

little like those from France, as they should,

given the widely varying terroirs of those

nations. Japanese drink beer or sake (itself a

beer) with the food grown from farms and

fished from the sea, and wines are almost

always a lesser match-up with sushi and

sashimi. The post-war affection for beef in

Japan has, oddly enough, caused the creation

of ultra-fatty wagyu beef, with which beer is

a decent accompaniment but big red American or

Australian wines are a much better

idea.

Sometimes there’s nothing

better than to slug down an ice cold bottle of

beer or Coke, and tea and coffee make for good

pick-me-ups all on their own. So can a glass

of wine, but it will be made better if there’s

some food on the table.

IT ALL BEGAN BACK IN 1959 WITH TANG

The

nation’s space agency has launched an

international competition called "Mars to

Table" to help feed astronauts stationed

on Mars, whereby American citizens may

create meals for an undetermined number of

people and win a $750,000 prize. The

system must be designed for growing and

producing food on Mars.

❖❖❖

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher

Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish.

Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2026